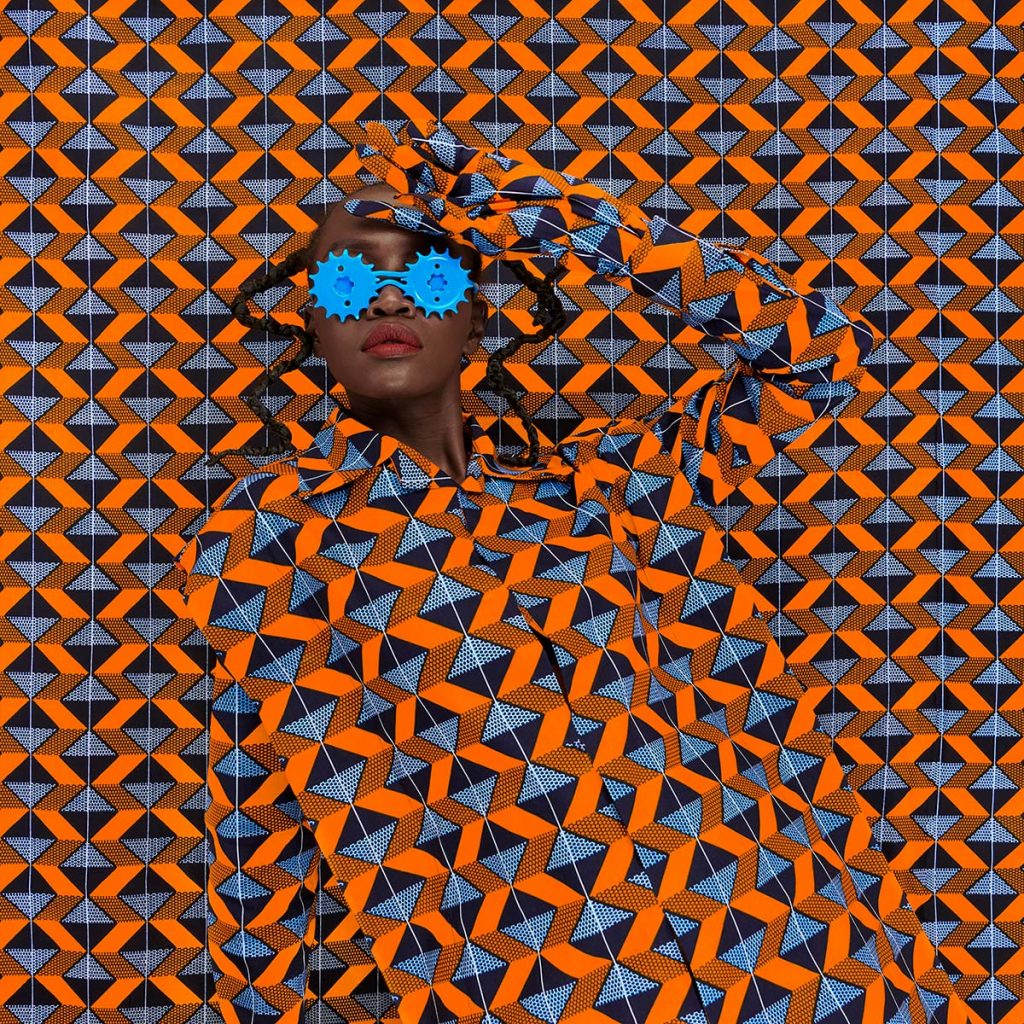

Whilst walking around the erected white walls in the gardens of Somerset House for Photo London earlier this year, my eyes were drawn to the series Camo.

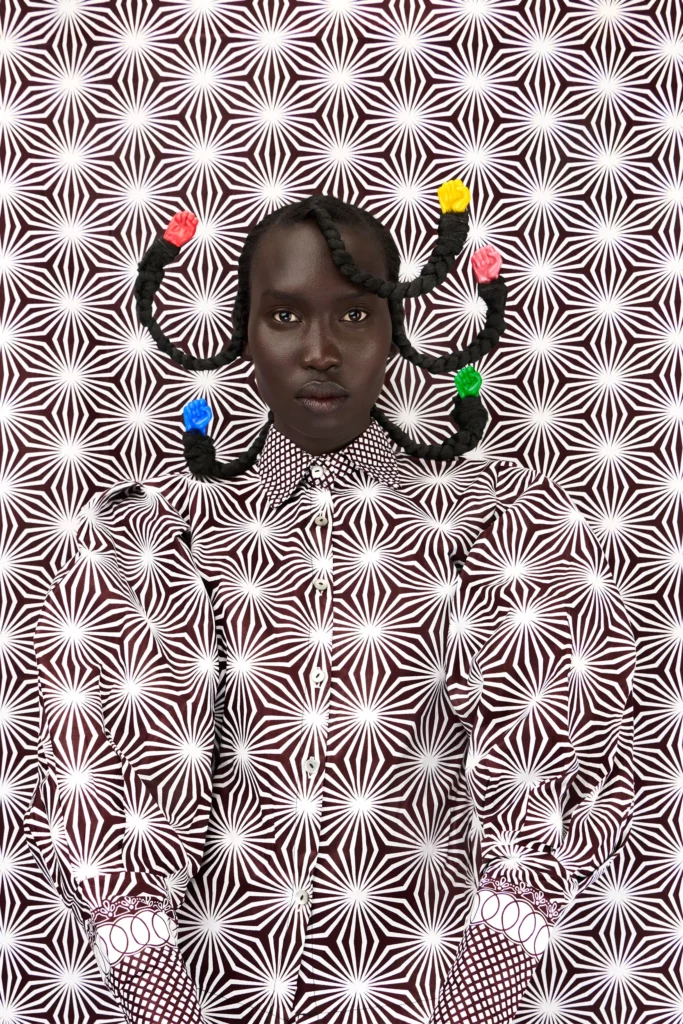

Breathtakingly colourful, the subjects of the photographs demand attention. Dressed in traditional Kenyan fabrics and adorned with reused objects such as hair pins for eyewear or cola bottles for curlers, the women may camouflage with their background, but in doing so they create an outstanding impression.

This is the work of self-taught photographer Thandiwe Muriu who was born in Nairobi, Kenya. At once recreating architectural and traditional beauty traditions in her work, Thandiwe reaches into the industrious nature of Kenyan culture to keep ancient practices alive, and even draws on Kenyan proverbs for inspiration. Her photographs are celebratory, both of the journey she has been through in accepting her own beauty, but also of the beauty within Kenya as a whole.

I caught up with Thandiwe to learn more about her practice and the motivations behind her Camo series.

What was your journey to becoming a photographer?

My journey began at 14 when my father taught my sisters and me how to use digital cameras. Before then, I felt that I had all this art inside of me that was looking for an outlet, but hadn’t yet found one. I couldn’t really draw or paint, but right from my first interaction with a camera I knew I had a connection to photography.

Every day after school I would rush home to finish my homework so I could spend my time photographing clouds, flowers and anything I could get my lens on before the light faded. My father had all these old photography magazines that I would pore over during the weekends. I was hungry to learn anything and everything!

My elder sister also used to collect Vogue magazines and over time I developed an interest in wanting to create pictures like the ones I saw on their covers; these magical, flawless images. I convinced both my sisters to model for me, using bed sheets as backgrounds to create elaborate shoots and for lighting, I used tin foil as a reflector. I wonder if my mother ever figured out where all her tin foil foil went!

I started putting the pictures from my shoots up on Facebook and about a year later somebody messaged me to ask how much I would charge for a photo session. I thought, ‘Wow! You mean I can get paid to do this?’ At this point I had no idea photography could be a career path and I was over the moon! By the time I was in university, I had a steady stream of small clients and enough savings to buy my first camera. I graduated from university with a degree in Marketing and felt pressure to consider the job offers I received. After watching me struggle to make up my mind, my father said to me:

“You love doing photography. Why would you consider doing anything else?”

Until that moment, I had never considered photography as a real career path). It’s as if a lightbulb went off in my head and I was free at last to fully pursue my passion. I moved from shooting portraits, over time, to corporate events, and then eventually ended up in commercial advertising photography, which is where I am today.

Can you tell us a bit more about the role camouflage plays in your work?

The series is titled Camo because of how the subject of each image camouflages into the background. It’s a commentary on how as individuals, we can lose ourselves to the expectations culture has on us, yet there are also unique and beautiful things about every individual which should be celebrated. It’s a little ironic- I want my models to blend into the background even as they stand out.

I didn’t initially plan for the series to be exclusively of women, but it was a natural starting point for me. I wanted to celebrate everything I had struggled with in my own beauty journey: my hair, my skin and my identity as a modern woman in a traditional culture.

It’s easy to see the African continent as lacking. The great need and poverty can easily distract from all the beauty and richness of the cultures in Africa. Africa is full of beautiful cultures and I am so proud to come from this continent!

To me, being African means being colourful and full of life. I think through Camo I have had the privilege of being able to highlight the humour, perseverance and diverse beauty of the continent, even as the models “camouflage” with their background fabrics.

What do you feel is the main motivation behind your work?

Camo began simply as a way of appreciating African fabrics. However, I quickly realised there is so much more depth and breadth to our culture beyond that. If I speak of African beauty, I need to focus on more than what we wear and explore who we are and how that makes us uniquely beautiful.

The objects I use in my work are items I interact with everyday as a Kenyan. They were used all throughout my childhood and my mother (and probably even my grandmother) interacted with them often throughout their lives.

Objects are an integral part of our daily lives and are often a big component of beauty culture. I’ve used bottle tops, plastic combs, sieves, straws and even bottle cleaning brushes in my images.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Kenyans are very resourceful people and one of the most common things I see is objects being used for more than just for their intended purpose. Plastic handheld mirrors are used not only to look at oneself, but also as side-mirrors on bicycles weaving through traffic, or even as decorative clothing accessories on a Maasai warrior! This inspired me to create fashionable eyewear from the plastics found in almost every shop here.

The eyewear in Camo 08 is made from hair pins often found at the hair stalls in distinct red and yellow fan-shaped holders. Those holders have remained unchanged since the 80s.

The bottle cap hair in Camo 11 is directly inspired by how soft drinks tie into my own culture. In the Kikuyu tribe, when a girl is getting married, sodas are used as part of the dowry negotiation process. If the bride-to-be consents to the marriages, she pours a soda for the in-laws when her fiancé comes formally to ask for her hand. The soda is almost always the traditional glass bottle vessel as opposed to soda held in cans or plastic bottles.

In Camo 23, I used parts of plastic hair combs as hair accessories. Those combs are universally used for everyday grooming here in Kenya by both men and women. No matter the type of home, everyone has one.

We often wear our hair in braids or get it chemically straightened, even though we have a rich history of beautiful, architectural hairstyles that are being forgotten. Our natural hairstyles as Africans/Kenyans are one of the most unique things about our beauty culture.

I’d hate to see it lost, so I incorporate it into my work to spark conversation around how we can wear traditional hairstyles today. I like to call it ‘modernising history’ – I draw from historical elements to inform our future generations about our past.

Camo 35 takes inspiration from watching your mother get her hair done at salons. What is your favourite memory from those spaces?

My mother would always go to a hair salon closest to where we lived, so the locations of these salons changed over the years as we moved around Nairobi. I would watch my mum sit on a chair as a hairdresser wound the chunky plastic rollers; then she would patiently wait under the dryer as the curls set.

The hairdresser would then unwind the rollers, lather different products, and style it all up into a hairstyle called Curly Kit. I’d say that my favourite memory was witnessing my mother’s moment of pride as she patted her perfect look one last time in front of a mirror before we walked out, her permed tresses wound into the large bouncy curls signature of the style.

This is why the electric blue eyewear of Camo 35 is made from plastic hair rollers. I wanted to honour the highly fashionable ‘Curly Kit’ 90s hairstyle.

What impression do you hope your work leaves on the viewer?

Generally we don’t share our African proverbs in everyday life. As children, we begrudgingly use them in inshas (Swahili for ‘essays’) in school and quickly move on. I try to re-ignite and celebrate the wisdom of our African proverbs in Camo. To provide an opportunity for people to begin to think about and hear our proverbs in a new and exciting way.

Also, our dark skin is one of our most striking features and I want to encourage young girls to celebrate that. Though these can often be heavy themes, I wanted to highlight them in a playful, easily approachable way.

So, Camo has been a way for me to discover and understand culture, see the beauty of some cultural practices I thought were outdated or unnecessary. It’s also been a way for me to find my joy in photography and remember what made me fall in love with it in the first place; why I’m so passionate about what I do and to continue to discover my voice in a new way.

What can you do?

- Check out all of Thandiwe Muriu’s work on her website.

- Follow Thandiwe Muriu on Instagram

- If in New York, go along and see Thandiwe Muriu’s solo show with Maison Kitsuné at 193 Gallery, on until 7th September 2022

- Read Don’t Touch My Hair by Emma Dabiri