I count myself among the lucky people who knew Ani Kayode Somtochukwu before his debut novel, And Then He Sang a Lullaby (“Lullaby”), the inaugural title from Roxanne Gay Books. The book is a love story between August and Segun that explores queer life and love in Nigeria amid state-sanctioned violence.

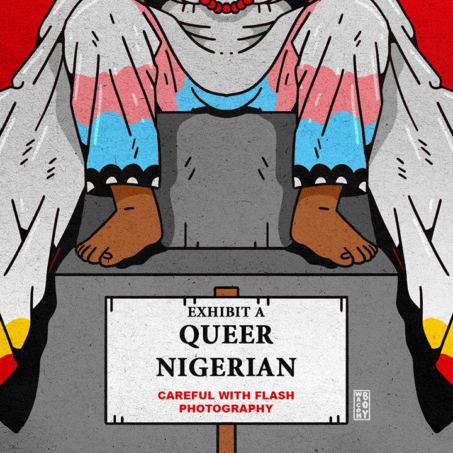

Several laws criminalise queer people in Nigeria, including the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (2013) (SSMPA) which criminalises same-sex unions with up to 14 years imprisonment. Penalties for queer people go as far as death in various Northern states in Nigeria that operate under the Sharia Law. These laws punish anything from how people dress and present themselves to witnessing and aiding same-sex marriages and unions.

These laws and the sociocultural context of Nigeria shape our understanding of ourselves and others, creating norms and justifying discrimination against queer Nigerians. This self-regulation and surveillance allow distant governance, as the society largely complies without much enforcement from the government. This has led to citizens being actively involved in the discrimination and violence resulting from these laws.

Lullaby delves into these aspects of queerness; from the more overtly political aspects of criminality and state-sanctioned homophobia, to the minutiae of shame and shaming, and how they manifest in our day-to-day lives, including the platonic, romantic and familial relationships we have with each other. We follow August and Segun individually and together as they navigate childhood and adolescence as queer people in Nigeria. Kayode skilfully connects these dynamics to expose their complexities and specificities to queer life in Nigeria.

I have had the opportunity to engage with Kayode on multiple occasions, and as such, our conversation was different from others I have spoken to for previous articles – there’s a familiarity here. I was speaking to a friend and someone with whom I share a common interest and investment: the Nigerian queer community.

I’ll be frank, there aren’t many queer activists in Nigeria whose politics I can wholeheartedly vouch for, but Kayode is one of those I can. Not because we always agree – we don’t – but because I know we have the same end goal and exist in similar paradigms. So even though we don’t always agree, I know our perspectives often sit side by side, rather than in opposition.

This makes challenging each other’s political positionings easy, and something we do when we speak about Lullaby. In fact, the words, “I disagree…” came up many times in our conversation – from both sides – and I am grateful for that, because I have learnt so much in the process.

Youthful angst

Our conversation starts by exploring the youthful angst and anger we see with Segun, one of the main characters in the book. It is one I also recognise in myself and Kayode. It is anger that is fuelled by unhappiness with the injustice in the world.

Relatively early in the book, another character, Trevor, asks Segun, “How long can one person realistically expect to sustain anger?” Segun replies, “For as long as there is something to be angry about.”

This anger often manifests in an uncompromising rage fuelled response to homophobic, transphobic and classist politics. These responses are explored in depth in Lullaby through Segun’s interactions with and reactions to homophobic people throughout the book. He expresses his anger by challenging old friends and strangers on social media platforms, and also confronts homophobic students at his university.

Kayode and I recollected how this anger showed up in the pair of us when we tag-teamed responses to a Nigerian TERF (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist) on Twitter a few years ago. This is something I admittedly don’t see myself doing anymore. Not because I’ve stopped caring, but mainly because my politics has evolved beyond simply expressing my care through anger, especially online.

I also quickly realised the toll the angst and anger had on me and my relationships. So, like Trevor, I questioned the sustainability of this angst and its alignment with the love and joy I long to experience.

Kayode challenged my question. “I don’t think it’s a question of sustainability,” he says. He contextualises this through Segun’s character, “I don’t really think someone like Segun would particularly care about the answer to this question.”

Kayode and Segun share the same sentiments about questioning the sustainability of anger in our liberation movements. Kayode sees the value of anger and writes this into one of the characters.

“I see a part of myself in all the characters,” says Kayode. While people often wonder if he is more like August because of his physical representation, he notes, “I put a lot of myself in Segun.” Knowing Kayode meant that I didn’t need to be told this to see it. As I read the book, I could almost hear Kayode’s voice at certain points when Segun spoke.

From his introduction, Segun experiences violence for being effeminate – it is almost inescapable. Therefore, the anger he experiences is justifiable. Some queer people are emotionally invested in liberation because of the specific ways that the violence queer people experience affects them. “There’s no way you can navigate that kind of direct aggression and physical confrontation against you without anger being a component,” Kayode says.

The place for anger in our movements

As Kayode speaks, a concern lingers in my mind. I wondered how this approach might impact queer people’s ability to embrace joy, love, and pleasure amidst our liberation movements if anger has to be such a key component. While these emotions can coexist, I couldn’t help but question what I sensed as an uncompromising stance on the necessity of anger held by Kayode (and Segun).

Kayode explains, “People approach the queer liberation movement in multiple ways.” Some people respond to queerphobic violence in Nigeria through anger and go on the attack and defence. However, this approach has various repercussions, including threats, violence and surveillance.

Kayode acknowledges, “Anger like this is dangerous, because it could make you unhappy all your life.” As mentioned in the book, Segun “called longtime friends devils, and blocked them. August was a bit afraid of all this anger…” Segun’s confrontations with online homophobes affect his mood, strain his relationship with August when he doesn’t see the same level of energy, and escalate into physical altercations.

On the other hand, some queer people respond to and repudiate the injustice by creating spaces of joy, love, and pleasure. They evade surveillance and state violence to support the community’s needs. This approach also has limitations because once we step out of these spaces, we are reminded of our criminality. As Kayode says, “Happiness like that just isn’t sustainable. You can feel peaceful for many hours, but you will still step outside at some point, and life will happen.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

“Queer liberation is the only sustainable solution”

Kayode says: “one of the things I really wish people would take from the book is that the solution to that unhappiness is to root out the cause of your unhappiness – which is queerphobic oppression. If you want to create happiness that is sustainable, something that follows you out of queer spaces and follows you to schools and government offices, and stretches and surrounds us, we have to destroy queerphobia. Queer liberation is the only sustainable solution.”

What I liked about his exploration of queer liberation is that it is not simply on the terms of identity, but a Marxist analysis of the material conditions in which queer people also exist. It’s a response that takes seriously the class dimensions of the queer struggle. Lullaby illustrates this through Segun’s experiences as a low-income individual navigating queerness.

I honestly wish more queer people considered this. My research on queer activism reveals a worrying classist bias in our liberation tactics. Instead of liberation for all queer people, the focus often lies on visibility and access to privileged spaces. This oversight extends to the one-dimensional view of queerness, disregarding other intersecting identities and positions.

If queer liberation is the only sustainable solution, then none of these approaches, be it the politics of in/visibility, joy, pleasure, love and/or anger, appear sustainable in isolation. To reconcile these perspectives, I’ve realised that rigidly adhering to any single perspective seems futile. We need to recognise our various experiences, strengths and capacities and how they influence our approaches. Therefore, strategic negotiation is vital, considering the context, space, and time for each approach. The most important thing is that we take action.

The Individual vs The Community

The tension between these various perspectives often manifests through how we see ourselves as individuals in relation to our communities, be it our familial, friendly, religious, or queer community.

August, the other main character in Lullaby, deals with this tension intensely. It was a “central core of his life. He is trying to understand where his community [family and queer] stops and where he, as an individual, begins.” As the last child and only son with three older sisters, August struggled with the responsibilities placed on him to carry on the family name. This is something his sisters tell him many times throughout the book. A core part of his story is trying to understand who he is outside of who his family and society tell him he should be.

August also faces pressure from Segun to confront his homophobic friends and family, who Segun believes threaten August’s identity as a queer individual. In our discussion, Kayode and I recognised the difficult position this puts August in. Kayode highlights Segun’s question, “Why are you friends with this person?” But for August, “This is my entire support system and everybody I know. If I remove every homophobe from my life, I have nobody but you, and I don’t even have you, per se.”

There are many queer Nigerians that experience this tension. They are torn between loyalty to significant people in their lives and allegiance to the queer community. Sadly, neither side is often willing to compromise or comprehend the complexity of this situation.

For Segun, this tension didn’t exist. Being effeminate, he faced inherent challenges in altering how society perceived him. From the start of the book, he is labelled an outsider due to his effeminacy. Consequently, he felt no pressure to conform to anyone’s expectations, as he was already seen as different.

As Kayode has mentioned that he put a lot of himself into Segun, it should come as no surprise that Kayode notes that the tension between the community and the individual is not something he experiences. Whereas, I share August and other queer Nigerians’ experience of this tension.

However, this was not a point of disagreement between Kayode and me. It reflects how our individual experiences cultivated our perspective of things and how those perspectives can (and have) come together to conceptualise queer liberation in ways that sit side by side. The fact that we sit side by side is a sign of community, but it is also a product of our individuality within that community.

Within the space where the individual and the community intersect, we find the power of charitable critique amid diverse perspectives. This tension enables us to hold each other accountable as a community while respecting and nurturing our individuality.

This is why Kayode and I can have conversations where we disagree. Yet, we leave the conversations laughing, hugging and somehow finding reasons to engage in conversation with each other again. We are individuals, but we recognise ourselves in community with each other.

A love story, first and foremost

I describe this book as a love story at the beginning mainly because of how it shows up and how Kayode sees it. It is deeply romantic at various points, reminiscent of adolescent crushes and love stories. It explores the idea of individuality and love within a community in complex ways.

How do two people like Segun and August love each other when they feel the tension of individuality and community differently? Kayode reminds me, “it’s not rosy; that’s real life. Sometimes, the person you love is not in the same place as you even though you really love each other.” This is particularly important where the socio-political milieu dictates the love you can have. “Rarely, love overpowers political considerations. It forces people to try to walk through insurmountable circumstances to be together.”

This exposes the need for liberation and the need for that liberation to be intersectional. It is a way to advocate for yourself and your right to love and joy. This is the ultimate act of self-love.

As Kayode says, “You cannot self-love your way out of being despised by your own society. A society that does not love you cannot be allowed to stand.” Then he echoed Segun’s character, “there is no way of declaring your own humanity more forcefully than rejecting a society that does not accept you, and saying that, ‘this society has to go, and I’m going to commit my life to bringing it to its knees.’ You cannot love yourself more than that in my opinion.”

So to answer an important question: can we find joy, happiness, pleasure and love if we are constantly fighting, angry, and resisting a society that despises us? For Kayode, “The response is that I’m always angry because of this unhappiness. So it’s like putting the cart before the horse.”

While I agree with this, I’m more inclined to propose a thought where the cart sits side by side with the horse. So the question for me becomes: how can we find joy, happiness and love while constantly fighting, angry and in resistance?

I don’t have the answer, to be very honest. But I suspect people are doing it. I know I am. And this is where individuality comes in. I know how I do that as an individual, so this is perhaps a question best answered as individuals and not as a community.

Often, communities such as queer and African do not have the luxury of being individuals, and are often seen in relation to a community. For us to be able to navigate the complex reactions of anger, joy, and love in a dehumanising space, we need to understand ourselves as individuals first and see how we fit within the community, what value we bring, and what tactics work best in a particular space and time. This is a politics that begins with oneself and not the hegemonic outside.

Yes, queer liberation is the only sustainable solution. However, I don’t see the value in saying we shouldn’t find ways to be happy or find joy until queer liberation comes. I believe we can do both. What is important is that we can hold space for accountability and critique when the joy we seek as individuals is antithetical to the community’s needs.

Lullaby provides the jump-off point to explore this tension, see the various perspectives and understand the conditions of the multiple answers.

What can you do?

- Read And Then He Sang a Lullaby by Ani Kayode Somtochukwu

- Listen to the Queer Circles Podcast on Queering Arts and Literature in Nigeria featuring Ani Kayode Somtochukwu and me.

- Read more about Ani Kayode Somtochukwu in the New York Times article

- Read This Body is an Old Road, one of my favourite essays by Ani Kayode Somtochukwu

- Read more articles by Adebayo: