What is the Rosebank oil field?

Despite warnings from climate scientists and experts, the UK government is hell-bent on extracting more oil and gas. The controversial Rosebank oil field – the biggest undeveloped field in the UK – could be approved any day now and would have significant impacts on the climate, oceans and energy security.

Rosebank lies west off the coast of the Shetland Islands in Scotland and is the biggest undeveloped field in the UK (and would be the third largest overall if built).

90% of Rosebank’s reserves are oil, which are likely to be exported – including to the European continent. Rosebank is nearly three times the size of Cambo – an oil field which is currently paused, since a successful campaign in 2021.

Equinor, an oil giant which is majority-owned by the Norwegian government, will own 80% of Rosebank after their acquisition of Canadian oil giant Suncor Energy, which has held a 40% stake. The last 20% is owned by Israeli firm Ithaca Energy, Cambo’s new owner.

In 2021, the Stop Cambo campaign successfully stopped the Cambo oil field by making Shell pull out of the project. The campaign is now aiming to stop the Rosebank oil field. Rosebank has drawn widespread public opposition including 700 scientists and academics, 200 organisations and celebrities, 40 MEPs and MPs from every major political party.

What would Rosebank’s climate impacts be?

Rosebank would emit over 200 million tonnes of CO2, which is more than the world’s 28 lowest-income countries emit in an entire year.

Burning the oil in existing UK oil and gas fields would push us past safe climate limits, and recently the UK’s Net zero tsar stressed that Rosebank would breach the UK’s climate target.

Scientists have said time and time again that we can’t have any more new oil and gas if we want to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Adding new reserves, like Rosebank, will push us closer to more parts of our world becoming uninhabitable. In 2021, the International Energy Agency, the world’s leading energy body, stressed that in order to stay within safe climate limits, there should not be any new coal, oil or gas developments.

Why is Rosebank a climate justice issue?

The CO2 from burning the fossil fuels in just this one single oil and gas field in the Global North would be more than the annual CO2 emissions of the 28 lowest income countries in the Global South combined. These are among the same countries that have contributed the least to the climate crisis who are already experiencing some of the worst impacts of an overheating planet.

Rosebank won’t do anything to lower energy bills in the UK, or make our energy supply safer – but will over a billion for oil and gas companies. 90% of the fuel extracted from Rosebank is oil, and will most likely be exported, like 80% of all North Sea oil. The little bit of gas that is extracted is more expensive than new UK renewables for generating electricity. Equinor will pass 91% of the cost of developing the Rosebank oil field to the UK public, while they take the profits, withT the UK public would hand over £3.75 billion in tax breaks to Rosebank’s owners. In February 2023, Equinor reported record profits of $75 billion.

Every new field is a delay to transition away from risky jobs in oil and gas to decent unionised green jobs. It locks workers and communities in places like Aberdeen into continued volatility. With the right support and investment – led by oil and gas workers, their unions and impacted communities – the move away from fossil fuels could see three jobs in clean energy for every oil and gas job.

What are Rosebank’s links to the wider problems of extraction and capitalism?

Rosebank is a prime example of fossil fuel capitalism.

The foundations of our current economic system (energy production, transportation, and various industrial processes) is hard-wired to run on fossil fuels. The capitalist principle of unlimited economic growth relies on the unlimited exploitation of the Earth’s resources with disregard to the detrimental consequences to our planet and its people.

This is why people like Jacob Rees Mogg say that ‘every last drop’ of the North Sea must be extracted and commodified. Fossil fuel capitalism allows for a privileged few to make record-breaking profits from burning dirty polluting fuels and trashing the ocean, while those already most marginalised must suffer the consequences.

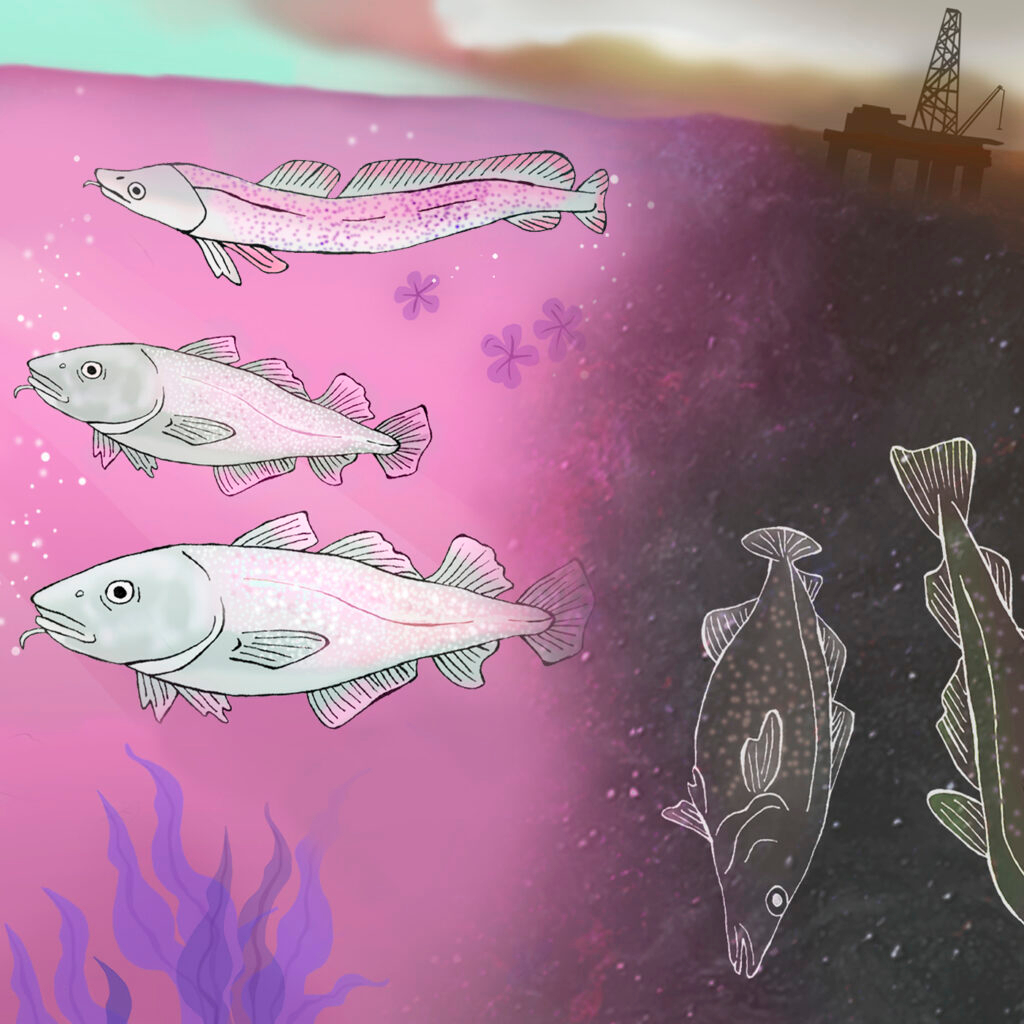

What are Rosebank’s impacts on marine life?

A recent report revealed the shocking extent of the damage to our seas caused by fossil fuel infrastructure.

Marine life is being threatened by direct pollution from production, including oil spills, deafening noise levels, and the release of microplastics and toxic chemicals. Of the nearly 900 locations offered for new oil and gas licences, 352 overlap with designated Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

The impacts of continued oil and gas production reduce our seas’ ability to act as a carbon store, both directly by degrading the marine environment and from increasing emissions. This means that climate impacts from the burning of fossil fuels are exacerbated by our seas’ limited ability to absorb excess carbon dioxide.

Undeveloped oil fields such as Rosebank and Cambo would see pipelines and infrastructure cut through the protected Faroe-Shetland Sponge Belt Nature Conservation MPA, causing habitat loss, disturbance, and pollution. This area is home to diverse sponge aggregations, long-finned pilot whales, Atlantic white-sided dolphins, and centuries-old ocean quahogs.

A significant oil spill from Rosebank could risk serious impact to these species in at least 16 UK Marine Protected Areas – a major blowout could reach not just the shores around Scotland and Norway but as far as the coasts of Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands.

Has Rosebank been approved yet?

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA, legally still known as the Oil and Gas Authority) and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero give out licences and permits to oil and gas companies. Oil and gas fields go through many stages, meaning that campaigning is important at every point in the timeline of a project. Licences generally run for three terms, the first one being exploration, the second project development, then production.

Once a licence is granted, it gives companies the opportunity to explore for and eventually produce oil and gas – but only if they pass a series of steps on the way. Here, it is important to note that a licensing round does not involve approving any new oil and gas projects – that happens at a later stage. There is also a difference between licensing rounds and production permits: A licence alone is not the same as approval to start drilling. You can learn more about the UK oil and gas approval process here.

The licences covering Rosebank date back to as early as 2001, and approval could come any day. In July 2023, it was reported that the decision will likely be delayed until after parliamentary recess in September, as the government’s oil and gas regulator is raising concerns over Rosebank being at odds with the UK’s legally-binding climate targets.

How can climate litigation be used as a tool to resist this?

Climate litigation is an increasingly powerful tool used by climate campaigners, with over 2,300 cases recorded across the world in the last year. More than 50% of climate cases end with favourable outcomes for climate action, and they are thought to contribute to policy decisions indirectly outside the courtroom too.

On 1st July, campaign group Uplift wrote to Secretary of State Grant Shapps and the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), stating that it has strong grounds to believe that an approval of Rosebank would be unlawful as it is not compatible with the UK’s climate targets and the environmental and marine impacts had not been considered sufficiently.

What action is taking place on the ground?

The field has been met with protest and resistance around the world – from the UK to Norway, Uganda to the US. The movement organised actions at Government buildings, Equinor headquarters in London, Aberdeen, Shetland and Norway; interventions targeting senior politicians and decision makers, knit-ins, ocean-focused paddle-outs and more.

In November 2022, a petition to stop the field, signed by over 130,000 people, was handed in at 10 Downing Street. Since then, 40 MEPs and 700 scientists and academics sent letters to prime minister Rishi Sunak urging him to stop the field from being approved; another open letter was signed by over 500 students and graduates, pledging that they refuse to work with insurance companies that fail to rule out funding for Rosebank or the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline.

In June, the Labour Party announced that it will block all new oil and gas fields if it is voted into government in 2024; and MPs from every major political party spoke out against Rosebank.

In a high-profile action at Equinor’s Annual General Meeting in Stavenger, Norway, campaigners organised an intervention urging the company to stop Rosebank.

Myth busting

Since the UK Labour Party announced their pledge to end all new oil and gas licences, there’s been an onslaught of misinformation and half-truths put forward by the oil and gas industry and several government ministers. Here are five of the most common claims:

- Stopping new oil and gas fields makes the UK dependent on foreign imports, driving up prices. In reality, new oil and gas fields do not lower bills and will do little to reduce imports, as most oil is exported anyway.

- We will need oil and gas for decades, so let’s keep drilling to use what we have. In reality, this is a misleading claim designed to delay climate action. All credible pathways to 1.5°C require a huge reduction in fossil fuels.

- A no new oil and gas policy throws workers on the scrapheap. In reality, oil and gas workers and unions are demanding clear pathways out of high-carbon jobs as they are projected to decline significantly by 2030 anyway because of declining reserves. A planned transition away from oil and gas creates job opportunities in alternative adjacent energy industries, which oil and gas workers often have the requisite skills for.

- UK oil and gas is “lower emissions”, which is based on a selective comparison for gas emissions, excludes oil, and focuses only on production emissions.

- Oil and gas companies are leading the transition, and stopping oil and gas production hampers their ability to invest in green technologies. In reality, for every $1 dollar invested in low carbon, oil companies invested $48 in fossil fuels and a further $39 in shareholder payouts.

How can I get involved with the campaign?

You can get involved with the #StopRosebank campaign wherever you are.

You can take a minute to take digital action right now or attend one of our events. Follow @stopcambo for more!

We have also developed a guide for influencers and ocean advocates.

What can you do?

Read:

- 5 Myths About Ending New Oil & Gas Licences and Permits

- Burnt: Fighting for Climate Justice by Chris Saltmarsh

- Oil and gas impacts on UK marine life

- Rosebank would bust the UK’s climate targets

- Explained: Greenwashed plans to power Rosebank with renewables

- UK Windfall tax loophole explained

- Exposed: Equinor’s five biggest climate crimes

- What could you get for the £500 million the UK is giving Equinor to go ahead with Rosebank?

- Explained: How does oil and gas licensing work?

- What does a fossil-free future have to do with the fight against sexual violence?

Groups to get involved with: