Journey’s Festival International, produced by ArtReach, began in Leicester in 2013 and has since grown to also deliver yearly festivals in Manchester and Portsmouth each October. The festival is a citywide annual arts festival running from 15-30 August, which curates, develops and commissions a varied programme by artists from refugee and asylum-seeking communities, bringing together work that explores the diversity of refugee experiences through artistic and creative encounters.

Opening on the 19th of August, and as part of this festival, is Enharmonic, a multimodal project by artist Miriam Bean which looks at traditions in music and sound, informed by the history of All Saints’ Church and objects within it.

shado sat down with Miriam ahead of the opening of her sound installation Enharmonic to find out more about the piece, the concept behind it and why this installation is one not to miss.

In amongst the festival’s packed programme of events, exhibitions and performances, Miriam has created space in the All Saints’ Church for people to come and experience something different. Through a series of workshops with local communities and the translation of graphic scores into music, Miriam has created over 200 tracks which bring together different musical interpretations of home, and providing a much-needed self-representative element to the narrative around those seeking refuge in new places. As Miriam explains,

I hope by being in the beautiful setting of All Saints’ Church, the audience feel able to walk around the space and experience the reverberation changing depending on where they are situated. Most importantly, I hope the work gives people a place to reflect upon the issues raised, and initiates conversations about sanctuary, belonging and identity.”

A grand piano sits in the middle of the space, central to the installation, both as an acoustic device and an aesthetic one.

Every day the sound installation changes, connecting a different, randomised combination of the musical tracks. Enharmonic explores how people listen and respond to sound in different ways and how music and culture is both shaped by, but can also hugely inform, a person’s identity. Music, in this sense, can be viewed as a cultural resource which continuously develops the idea of shared and individual identity.

At the heart of the project, and the seed from which Enharmonic grew, is the Lebanese song Atouna El Toufoule (translated into English: ‘Give Us Childhood’) – which has become synonymous with the title ‘Hamza’s song’. Hamza, a 10-year-old Syrian child now living in Jordan, was the inspiration for Miriam’s project. He sings lyrics which narrate his adolescence; an innocence robbed by conflict in his homeland.

Oh world

My land is burnt

My land is stolen freedom

…

Give us peace

And give us childhood.

Hamza’s song struck a particular chord with international Arabic-speaking audiences in the aftermath of the outbreak of war in Syria, and Miriam was no exception; “I was struck by how this simple song was able to convey so much, and how I couldn’t begin to imagine what he has gone through, at such a young age. I wanted to share this music and reimagine it as a composition and installation, so others could hear his song.”

For the installation, five musicians (Josh Semans, Mirka Hoppari, John Bean, Alison Bean and Martha Bean) recorded a number of short fragments from Atouna El Toufoule, with manipulations to speed, rhythms and dynamics of the Lebanese original. They also recorded sustained notes and improvisations around the tones – these separate tracks are all played at random so you will never hear the same thing from day to day.

What excites us most about Enharmonic is the unique and very personal way in which Miriam invites the audience to develop their own responses to the sounds and music. Regardless of age, musical preference, or native language, the installation offers an opportunity for anyone to experience and contemplate stories of home, music and identity. Music may be a universal language, but it can elicit a complete range of responses from those who listen. The same is to be expected from Enharmonic. Miriam states: “If it sparks any feeling, whether it is tranquility or discomfort, sadness or frustration, I think it has worked.”

Music provides a space not only for the expression of identity, but also brings new meaning to those who might listen – in this case, the audience in All Saints’ Church. Miriam has harnessed onto the role music plays in storytelling, and in particular the power of music to help “us to connect with each other through mutual tastes and experiences.”

She goes on to say, “Depending on where and when we grow up, we are exposed to a particular palette of sounds, or musical ‘modes’ which have evolved over centuries. Also, music is deeply connected to our capacity for creating memories, triggering moments from our past to vividly reappear in our minds. “

Stories are a powerful way to bring people together; moments shared and passed on by individuals, friends and families despite context or place. It is the process and practice of storytelling which lies at the centre of this project and which makes Enharmonic so important. Miriam explains that members from the local refugee and asylum seeking community were invited to come and share their stories, for them to be translated into music.

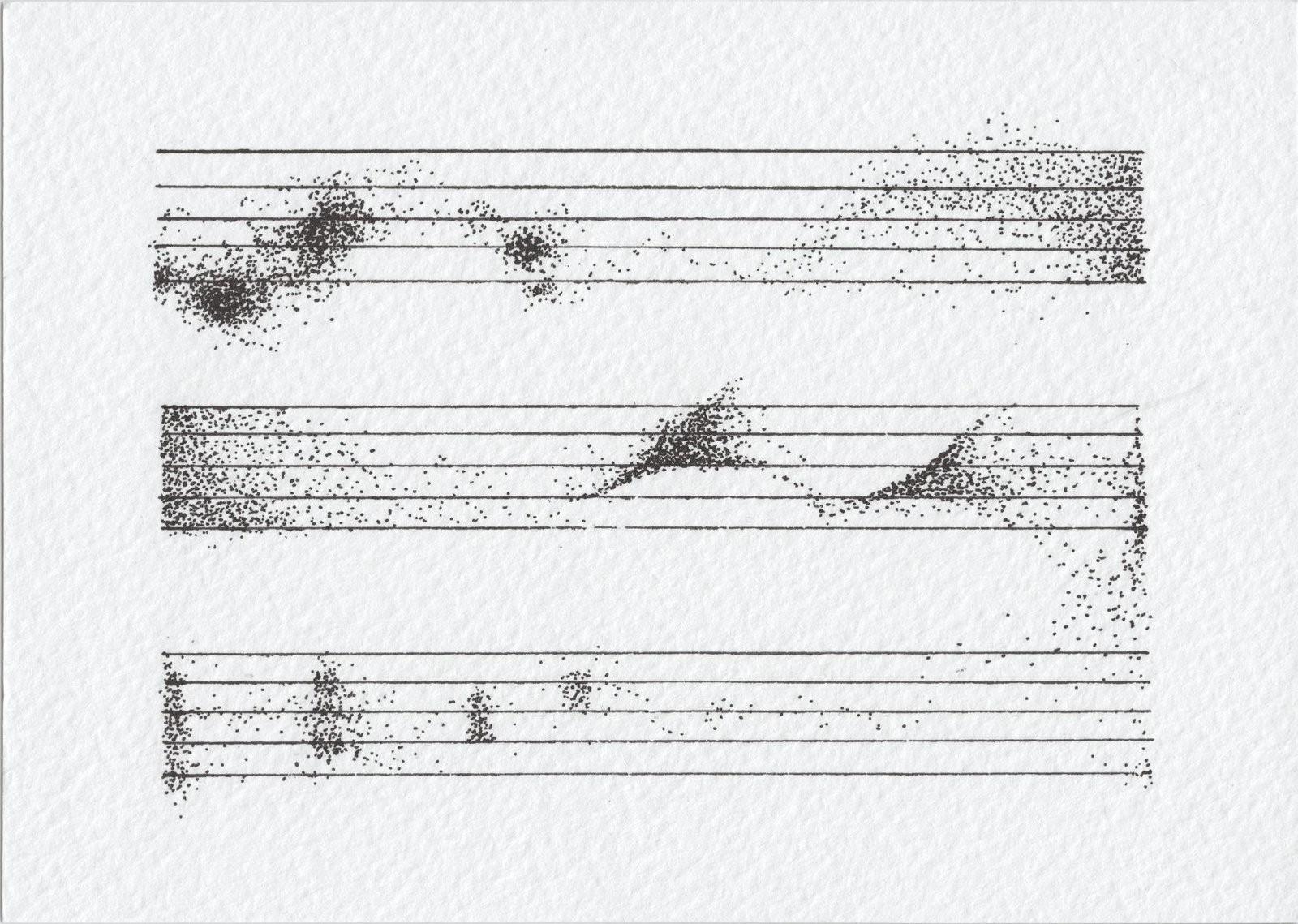

“By reflecting upon their personal experiences”, she says, “they were able to draw graphic representations of their journeys on paper, and then have these interpreted as music. It was this process, Miriam explains which allowed the group, who all have different backgrounds and speak a variety of languages “to express themselves and experience music in a new way”.

As an artist, Miriam has concentrated a lot on noise and dissonance, which has informed her approach with Enharmonic – where the process begins with a story told through a drawing; translated into a graphic scores, to then be interpreted into sound by musicians.

Stemming from her research into sound perception and, in particular, how we define noise and music, on a social level as well as a physiological one, Miriam discusses how she “began to question ownership of sound, and how ‘composed’ a piece of music or sound art has to be in order for it to belong to the artist”.

The artist goes on to explain how this research informed her decision to use graphic scores for this project; “When using conventional western notation, there are distinct roles for the composer and performer, however by using graphic scores, both the composer and performers do not need to have in depth knowledge of music theory in order to create something, making the process accessible to everyone.”

This same accessibility is shown in Miriam’s emphasis that, “it doesn’t matter where you’re from or what language you speak, music is for everyone.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

The installation opens today, and will run through to the 25th, where there will be a special performance of Enharmonic Live at 7.30pm. Co-composed by Miriam and her mother, composer Alison Bean, Enharmonic Live sees musical material similarly developed from Atouna El Toufoule and informed by the stories told by participants throughout the project’s journey, with Josh Semans on the iconic ondes martenot, Elizabeth Paling on the viola, John Bean on the cello, Alison Bean on double bass and Anne Heney on piano – all under the reliable baton of conductor Willard Welsford.

If you are in Leicester this week, make sure to go and experience Enharmonic for yourselves!

With a huge array of events, live performances and concerts, there really is something for everyone to enjoy at this year’s festival.

To make your plans for the festival download your own copy of the full programme here or grab yourself a printed brochure from LCB Depot.

To find out more head to www.journeysfestival.com

Twitter | FB | Instagram @journesfest / #JFILEICS

See more of Miriam’s work on her website and instagram