Seven minutes. A trained medical professional can conduct an emergency birth in seven minutes. If a baby is not born in those seven minutes, oxygen deprivation and physical distress to the infant’s body can occur. The infant will have an increased chance of Cerebral Palsy, brain damage, blindness or death. The Mother may experience excessive bleeding, genital tearing and death. Healthcare workers that support an emergency birth have seven minutes to make decisions that could have life-altering consequences for patients and their families.

Sara* heard the emergency birth alarm on her ward. Despite being one of the few doctors across her health board to be able to deliver babies, she had been diverted from her role as an OB/GYN to support general medicine colleagues working towards containing the spread of COVID-19. But when she heard the alarm, she knew she was potentially the only doctor on roster who could help, so she ran towards the alarm.

The woman in the midst of her emergency birth was suspected of having COVID-19. The five other healthcare workers who had rushed to her side had sufficient PPE. But Sara didn’t, she didn’t have a mask. “My colleagues were in distress; the pregnant woman was in distress and there was a baby’s life at stake”.

Official guidelines required Sara to wait for a mask to be found. But the emergency delivery had begun three minutes prior. Sara wasn’t measuring the minutes, she was calculating the accumulated costs of waiting any longer: sick baby, sick mother, tick tock, dead baby, dead mother, tick tock. PPE had been scarce not only across the hospital but within the whole of the NHS when the pandemic struck, it would be hard to quickly find the requisite PPE. “I couldn’t wait. I have the skills to deliver a healthy baby. I had to try”. Sara delivered a healthy baby without a mask, exposing herself to the risk of contracting COVID-19.

This is the UK in 2020 in the midst of a pandemic.

The Mystic and the Scalpel: the pregnant body amongst us

Our relationship to the pregnant body seems simple. The ubiquity of celebrities posing naked on the cover of Vanity Fair with coquettish smiles and pregnant wombs disguises that childbirth continues to be violent and messy. As reality star Cyn Santana recounts, “you’re bleeding, it’s burning… you crap, you vomit, you sweat, you don’t eat… then they have the nerve to throw this baby on you and tell you take it home”. The understanding of pregnancy has entered a weird conflict of its branding, as a moment of Laura Ashley serenity versus its reality, where the bottom half of a woman’s body is torn open so that new life can emerge.

COVID-19 has revealed the various cleavages in our society as to our assumed understandings of how medical care works and how it actually works. Childbirth during COVID-19 is one such event – childbirth was always a community event that we have turned into a sterile procedure. The pregnant body once occupied a place of secrecy, it was women’s business. Until a few decades ago when the pregnant body was ushered towards biomedical care with its hygienic practices and systematic medical procedures. Humans found a way to control fertility through effective contraception and safer childbirth. But some of those so called superstitions that were not as easily translatable to medical care have also been lost and they formed an important component to the birth experience.

Whereas, mystic understandings once dominated our understanding of childbirth to the detriment of the physical safety of the pregnant body, biomedical understandings of childbirth sometimes abandon the emotional and chemical realities of labour. Families and communities have often had to step in to cater to the emotional health of a pregnant woman. But during COVID-19, the pregnant woman is alone. In a clinical environment surrounded by stressed healthcare workers without sufficient PPE.

People like Sara step in to save lives but are too under resourced to also often provide the fuller care that they wish they could provide. “I feel bad, pregnant women are coming in and giving birth with no one around them, being asked to constantly make decisions, being asked to fill in paperwork – exhausted from the process of labour. We try to help them but we can’t make decisions on their behalf and we have to rush to the next patient”. During COVID-19, the sterility and the isolation of modern childbirth is further reduced to the immediate essentials of medical procedures not medical care.

Phone calling the midwife and the obstetrician

The pandemic has reprioritised the scope and delivery of health services across the NHS. Organisations that provide sexual and reproductive health services throughout the UK have had to suspend “many ‘usual’ functions” in order to contain the spread of COVID-19. Remote healthcare via telephone or online pathways has become the new normal for women seeking sexual and reproductive health care. The College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (the RCOG) states there has been a reprioritisation of the healthcare of women and girls. “Some services have been postponed while other rely more on remote consultation and assessment. In some cases, this will have inevitably led to anxiety, distress and, potentially, adverse outcomes”. Stories of those ‘adverse outcomes’ are emerging but without consideration of the context and the policy failures that preceded the pandemic.

Disruptions that cause ‘adverse outcomes’ within sexual and reproductive health services is a feature of the COVID-19 landscape. But “budget cuts, services cuts [and] staffing shortages” has been an increasing trend in maternity care for at least the last ten years across the NHS. Despite an increase of complex childbirths in the UK there has been a decrease in the number of maternity care staff to support pregnant women. The Royal College of Midwives (the RCM) has compiled mounting evidence of a culture of burnout cycles wherein which Midwives are “Regularly working beyond [their] contracted hours, unable to take breaks for food, or even a trip to the loo”. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (the RCOG) reported that in a survey of doctors across specialities, “36% of obstetricians and gynaecologists met the criteria for burnout and were six times more likely to experience suicidal thoughts”. This has implications for the level of maternity care across the UK, as NHS staff who are subject to burnout are “more likely to practice ‘defensively’ – meaning a doctor may avoid difficult cases or procedures, over prescribe medications…”.

Sara shared that support of maternity care has not improved during COVID-19, “I got in trouble for not waiting for a mask – I didn’t follow procedure”. Subsequently when the pregnant woman whose emergency birth she assisted on was found to have COVID-19, Sara requested a COVID-19 test and was denied. Sara asked why and she was told, “I wasn’t a priority for testing, I was told to wait for symptoms. You can still spread COVID-19 when you’re asymptomatic. But I was advised to continue working”. Recent guidelines confirm this understanding. If a NHS worker is exposed to COVID-19 they are obligated to tell their line manager who has the discretion to determine whether further testing is necessary. “I think I should have been tested and I wasn’t. I don’t think maternity care is the priority in this current landscape”.

The COVID-19 delay to maternity care

Globally there has been a reduction of maternal mortality rates “due to interdisciplinary efforts that used multiple approaches to increase service availability”. An early framework identified by the World Health Organisation was the Three-Delays model. This model ultimately perceives that there are three delays that inhibit a woman’s access to medical care (1) deciding to seek appropriate medical help for an obstetric emergency; (2) reaching an appropriate obstetric facility; and, (3) receiving adequate care when a facility is reached. All three delays have been activated in a COVID-19 setting in the UK.

Currently, women in the UK have restricted access to under-resourced medical staff that are limited in the number of women that they can see. Those small group of women are then met with under-resourced and understaffed facilities. The ‘adverse outcomes’ predicted by the RCOG is a diplomatic understatement that prophesies unnecessary health complications and staff burnouts resulting in the deaths of mothers and infants.

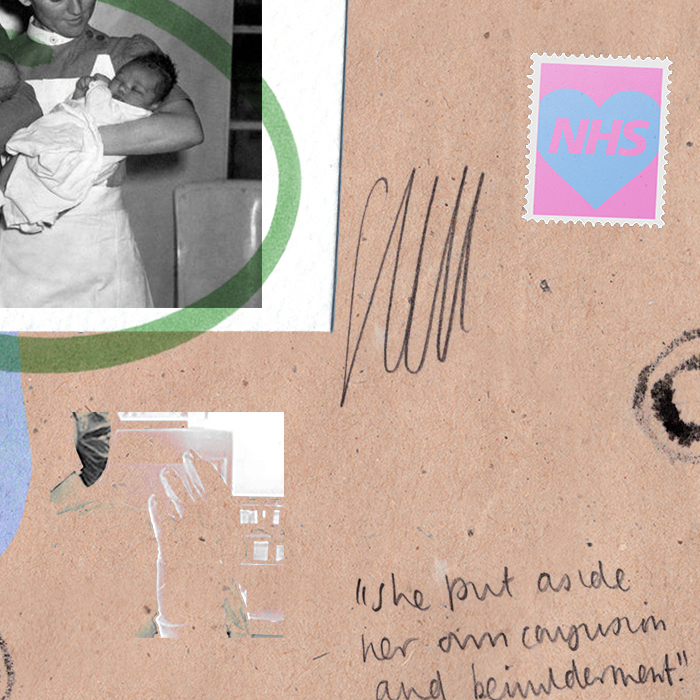

However, during this pandemic, a little boy and his mother got lucky. Sara stepped in and attended to his Mother’s birth. Sara disregarded her own burnout and the continual lack of support of policies directed towards maternity care in the UK. She put aside her own confusion and bewilderment that she had been inserted into since the emergence of COVID-19.

A young female doctor placed her health, and potentially her life, in jeopardy to save her patients. She did it because she feared that the required equipment to protect her would not be found in time, “it wasn’t a choice, it was instinct”. I ask Sara what she did after she performed the necessary procedures to ensure the survival of mother and the infant that had been thrust into her care, “I went back to work”.

*Not her real name.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

See more of Rosie’s work on her Instagram @rosiewainwright