The blood shall be a sign for you, on the houses where you are.

-Exodus, 12:13.

The house of my people

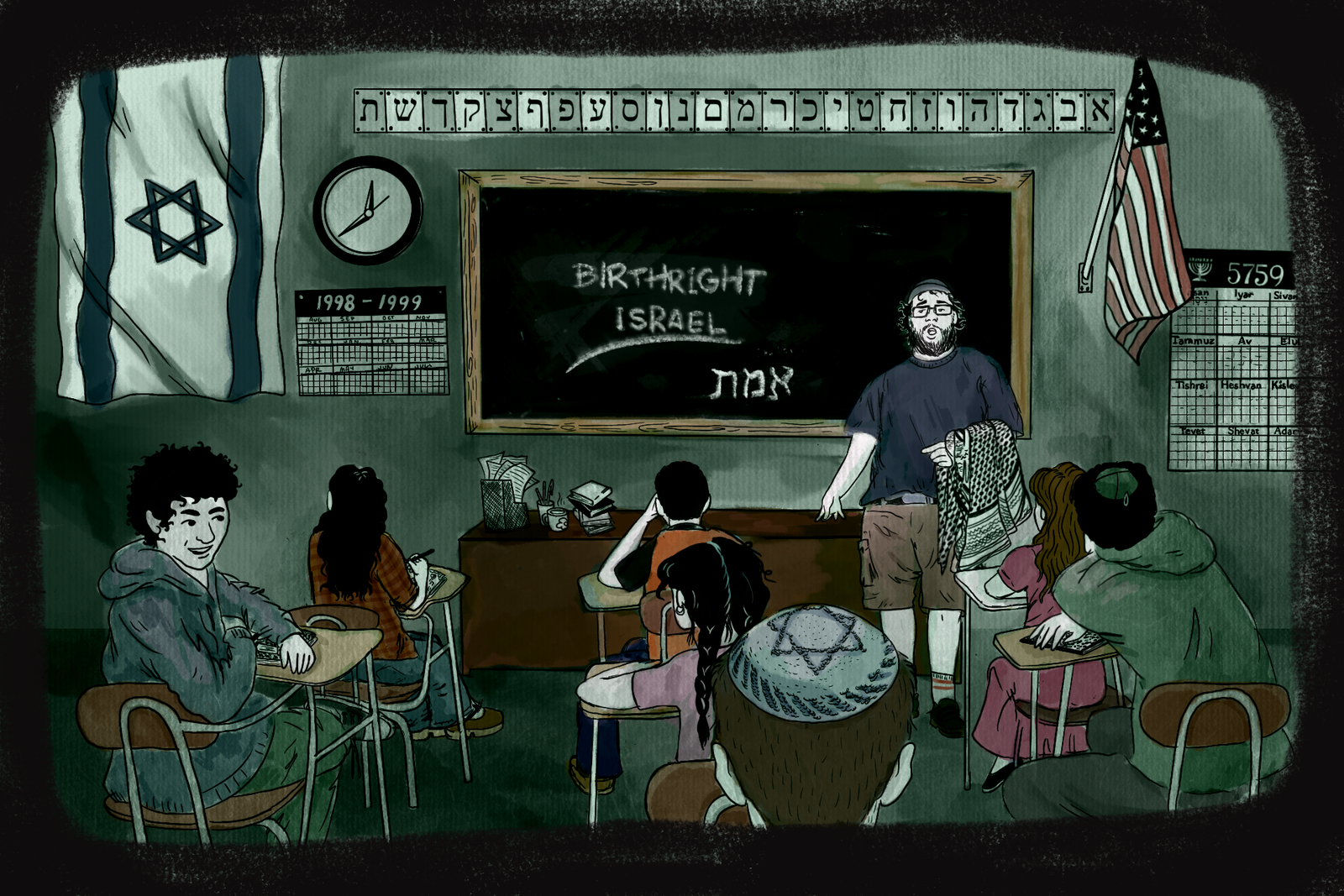

It was a lesson that I surmise wasn’t supposed to happen; it’s difficult to imagine it happening at any other Hebrew school. I was 12, it was a Saturday morning in Rockville, Maryland, the teacher was wearing cargo shorts and a navy blue t-shirt. Kids made fun of him a lot, I probably did, too.

That day he said he was going to do some role-play. He left the room and re-entered the classroom a minute later.

“My name is [I don’t remember], and I live in Israel,” he said. This wasn’t hard to fathom; there was an Israeli flag perched on two hooks hanging from the ceiling, after all, and he was a Jew, and Jews look like us, and our temple, Beth Ami, means “house of my people.”

The teacher talked about his spiritual connection to the ‘Israeli’ land, the warmth of the sun on his face, the feeling of community he experienced being amongst his people. He talked about how he’d moved here to his homeland and now was happy. He talked about his birthright. He spoke in English. He said he felt safe.

He left the room again, and when he returned he was wearing a hijab.

He introduced himself as a woman living in Israel. “I lack civil rights,” he said. “I’m a second-class citizen,” he said. “Settlers attack my relatives in the West Bank monthly. Many of my family members are dead, they were killed in the Intifada,” he said.

Looking back now, the Second Intifada hadn’t happened yet; it was 1999, the year “Birthright Israel” was initiated, granting Jews 18-26 years of age a free trip to Israel for 10 days. There was a lot of excitement amongst us students. We couldn’t wait to become older, to visit our homeland, to become ourselves, but this lesson hardly seemed like a commercial for it.

“My family lived in Palestine for generations, for hundreds of years, but we were forced out during the Nakba,” he said. “Do you know what the Nakba is?” he asked us. We didn’t know what in hell he was talking about. We didn’t even really know what Palestine was; we were only taught about Israel.

As a reform Jew, despite being religiously lax, I had learned we were a persecuted people, a wandering people, and I was proud of it; proud to be a Jew among many non-Jews. I felt a kind of righteousness in being persecuted, that sense I could do no wrong, because I was fundamentally and historically wronged.

But here was this man, dressing up as a woman, telling me that not only had Israel been founded on a land where people already lived, and had lived, and had then forced them out, but additionally, Israel continued to oppress and persecute them.

I had been taught that our Ten Commandments, our covenant with God, came about as a result of our persecution, our bondage. And that in escaping from the land of bondage, Israel was promised to us. In ancient Egypt they were killing all the male-born Jewish babies, I’d learned, so that the Jews would not rise up. But now, this “Palestinian woman” was telling me of all her young sons and grandsons killed.

House rules

After the teacher left and then returned for the final time with his regular clothes, I don’t remember what we talked about. I remember for the rest of the day we made fun of him mercilessly between class periods. We made fun of him mostly for dressing like a woman.

When I think about it now, when I think about why he dressed up as a woman, I think first about why he didn’t have to dress up at all in order to be an Israeli. Why dress up as someone like us; why disguise yourself as yourself? Thus, in order to become Palestinian, in order to Other himself, in order to become Arab, he had to become a woman.

I never ended up going on Birthright Israel and I resolved I never would; Israel didn’t seem safe to me anyway. We were always hearing about bombings and attacks, though no one ever explained to me why, except to fold it into the traditional teaching of atavistic anti-Semitism. But after this classroom lesson I wondered: why wouldn’t there be bombings? It seemed explicable: oppress a people, the people rise to resist.

This feels like a general rule, but it’s also particular to us: that’s the origin story of the Jews. How were we forgetting this? How could Jews be capable of creating a government that manufactured secondhand citizens? How could Jews effectively diasporise a people, while also ghettoising them? Is our current safety predicated on the erasure, cultural and historical and physical, of another people? I had never learned any of this. I didn’t know what Zionism was. I had only been taught that this was Jewishness.

Anti-Semitism is supposed to mean prejudice against Jews, but what does it mean to be a Jew? And what happens if the people in power over the very meaning of Jewishness are, on the one hand, white supremacists in America, and on the other, vowing the “conquering and cleansing” of Gaza by and for Israel?

This land is my land; it was never your land.

Gaza, since 2007, had been under military blockade with strict limits on the entry of goods, including a strict “calorie count” to keep Palestinians in a state of hunger while avoiding breaching international law’s definition of a humanitarian crisis.

In the past year and a half, such “scruples” are all out the window, with over 60,000 Gazans killed by the Israeli army, and we’ve watched (we’ve watched!) them starve as a result of a total embargo on food truck entry for the past four months.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

It is just and it is moral and it is historically required to be opposed to such things: to be opposed to what Israel is doing. And yet according to the Trump administration, these anti-poor, climate change-denying, condo-developing ethnonationalists, being Jewish and being in support of Jews is to be pro-Israel, and to be anti-Israel is to be anti-Semitic.

These charges of anti-Semitism have been extremely useful for the Trump administration. Any educational programme that teaches a history the administration finds inappropriate to its vision of the future, accuse it of anti-Semitism. They accuse the universities of anti-Semitism and thereby justify cutting off aid until the universities acquiesce to anti-DEI measures.

It would be neat and nice to say that it is a circular argument, or a contradiction, to call an anti-discrimination system “discriminatory.” However, this is not the case. Rather, it operates exactly as charges of anti-Semitism do; it promotes a very particular ideology while masquerading as a universal one.

Just as Zionism is the only protected subsection of Jewishness, so too here is whiteness the only protected racial category. It is for this reason that the Arlington National Cemetery’s website has been scrubbed of the names of its Hispanic, Black, and female service members. It is for this reason that Mount Denali, an Indigenous name, is now to be called Mount McKinley. It is for this reason that passports now only recognise two genders. It is for this reason that critical race theory (or, literally, teaching the actual and foundational history of American slavery) “endangers” our children by making them “uncomfy” of their race.

It is for this reason that immigrants are detained extrajudicially in Guantanamo and El Salvador and Alligator Alcatraz in the Everglades. It is for this reason that birthright citizenship in America is under threat: by claiming that immigrants have no right to citizenship if they were not born of American parents, the Trump administration seeks to erase our own history of having had no birthright to this land when we originally, yes, stole and conquered it.

The White House

Jewishness in the discourse of the right has been remade in the image of whiteness. Whiteness is a cultural category, not an essential one; it’s built on blood. Just like America is built on the blood of Black bodies – just like, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in Between the World and Me, “Black life is cheap, but in America Black bodies are a natural resource of incomparable value” – so Israel is built on the blood of Palestinians.

Trump’s executive orders are aimed against the fact that whiteness is a fiction: to preserve this fiction, you must erase history. The maintenance of such supremacy requires blood, and we see its reenactment in Israel, we see its lethal staging in Gaza.

When the Jews were granted their own state, the West implicitly admitted that anti-Semitism will never be rooted from the earth. Rather than fight anti-Semitism culturally, educationally, legislatively, the choice was made to in fact remove Jews from the “West” as we know it, to militarily remove the Palestinians from their own land, to continue the cycle of violence by displacing the cycle.

The Jews were offered a series of contradictions: you are western, but you will be situated in the Middle East. You are white, but not white enough to continue to live among us. You will establish and maintain your whiteness the same way we established ours: through a rhetoric of manifest destiny. Through birthright. Through expansion.

Jewish identity and charges of anti-Semitism are a straw man, an able tool of distraction. Both the false claims of antisemitism as well as the manufacturing of real antisemitic sentiments combine to form a state program; it is a necessary form of intolerance.

We’re being played, all of us.

Secure the perimeter

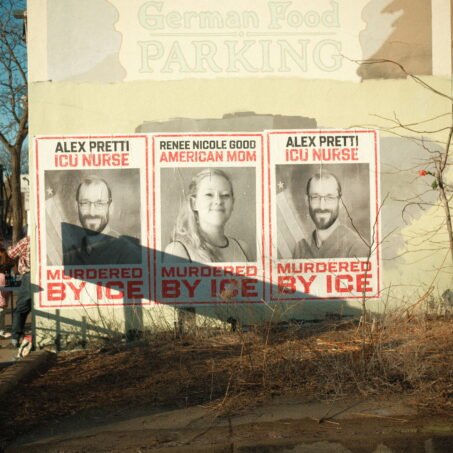

The misrepresentative charges of anti-Semitism are transforming Jews into human shields. When the Trump administration detained Mahmoud Khalil on charges of anti-Semitism, they were saying “Don’t blame us, blame the Jews.” When the Trump administration froze funding for our largest universities’ ability to conduct research in the name of anti-Semitism, they were saying “Don’t blame us, blame the Jews.”

The problem with such rhetorical effects is that they conjure material consequences: they anoint the event with Jewish hatred. The Trump administration does not care about Palestinian or Jewish safety; the Trump administration is only too happy to watch Islamophobia and anti-Semitism rise in tandem, as it distracts from the real questions we should be asking: How can you deport a person who has a legal right to be here? How can you deport a person for their views, when you yourself cannot stop screaming about free speech?

The same is true of when Israel uses Hamas as its own human shield, by accusing Hamas of using human shields: “Civilians die when Hamas uses human shields,” or “Hamas is keeping all the food to itself.”

This only further stokes hatred and incites more violence against Palestinians. It sidesteps the main questions, such as “even if Hamas hides within civilian infrastructure sites, doesn’t international law nonetheless prohibit you from attacking?” or “Is it not collective punishment to starve an entire population, and to weaponise the distribution of food through constant displacement?”

Bringing it home

I began this essay on my Jewishness but I am not interested in asserting my Jewishness, nor in decrying it, nor in defending it. I do not wish to carve out an identity nor to purify, conquer, cleanse Jewishness. I don’t have the bandwidth, the money, the media channels, the levers of federal funding, I have no material means of commanding or reshaping the narrative of what Jewishness is or was or should be or shouldn’t be.

When I play their game I only reinforce their terms and I lose. Responding to ethnonationalism with ethnonationalism only amplifies ethnonationalism.

And even more than that, when I myself distract myself with the very same straw man – anti-Semitism – I distract myself from the issue at hand, which is Palestine; Sudan; Ukraine; global climate change; actual anti-Semitism; the worldwide rise of totalitarianism; Islamophobia; the privatisation of warfare; white supremacy; domestic terrorism; homophobia; the vanishing of the middle class; the assault on women’s bodily autonomy; attacks on universities (their physical destruction in Gaza, their fiscal/curricular straitjacketing in America); transphobia; the threat of global inflation as caused by President Trump’s tariffs, themselves justified by ethnonationalist fervour.

I say “issue” in the singular because these items form an interconnected tapestry, these things are not disconnected, and despite the isolationist rhetoric that pits Us against Them, neither are we.

Homefront

I teach at a university now. This past semester we read Solmaz Sharif’s poetry collection LOOK, which investigates America’s invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq not only through brutal descriptions of destruction on the on-site battlefields, but the way war infiltrates our very language in our seemingly domestic spheres. In forcing us to “look” at literally weaponised language, Sharif also reveals what this language had hitherto prevented us from seeing: the more the ruling powers can separate and isolate us, the more targetable we become, for destruction, for extraction.

These lessons were familiar to my students, which shouldn’t have surprised me: my students are used to being targeted for their race, their gender, their sexuality, their religion, their ethnicity. But it was also eerily familiar to our era. The executive order, “Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of The United States by Tren De Aragua,” had just been passed. The order invokes this war-time power to remove “alien enemies,” i.e. to extrajudicially deport people.

How does the executive order justify its invocation of the Alien Enemies Act? By claiming – and this is repeated language that is so strange it seems to admits its own strangeness – we are experiencing “irregular warfare.” As Muriel Rukeyser writes in LOOK’s epigraph, “That policy was to win the war first, and work out the meanings afterward.” We were working to recover these meanings.

Nonetheless I had one student who said, “Are there justifiable invasions?” And I said, “Even the words ‘justifiable invasions’ should give us pause. Where does that phrase come from? Whose interests does that phrase represent? Who makes the justifications here?”

I write this essay now as a teacher who became a teacher because as a young student a teacher taught me something I wasn’t supposed to learn, something un-institutional and unjustifiable, something about justice.

I’m tired of justifications for unjust things. I’m tired of being told that we protect American jobs by triggering a global recession. I’m tired of being told we protect freedom of speech by removing dissenting voices from websites, from events, from the country, from history. I’m tired of being told that we protect American democracy by allowing ICE to have absolute jurisdiction to detain anyone. I’m tired of being told we fight racism by taking down the Black Lives Matter Plaza mural in DC. I’m tired of being told we fight anti-Semitism by redefining the Jew as pro-genocide. I’m tired of being told that calling something “genocide” is more upsetting than genocide. “Let it matter what we call a thing,” Sharif teaches us.

There’s a reason they won’t let us. To call something a war crime means a crime against their war, against their highest dollar value item.

What can you do?

Reading:

-

-

- LOOK by Solmaz Sharif, Graywolf Books, 2016.

- Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, tr. Elisabeth Jaquette, New Directions, 2020

- One day, everyone will have always been against this by Omar El Akkad, Penguin, 2025

- Recognizing the Stranger: on Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad, Grove Atlantic, 2024.

- Hamas Contained: A History of Palestinian Resistance by Tareq Baconi, Stanford University Press, 2018.

- Except for Palestine: The Limits of Progressive Politics by Marc Lamont Hill and Mitchell Plitnick, The New Press, 2021.

- Articles about Palestine

-

Aid, organisations and resources:

-

-

- Palestine Children’s Relief Fund

- Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel

- UN’s 2025 list of companies complicit in Israel’s genocide

- Writers Against the War on Gaza

- Photojournalist, artist, and activist Bisan Owda’s Instagram account

- Jewish Voice for Peace

- Palestinian Youth Movement

- IfNotNow

-