Seeking asylum in the Age of Offshoring

Shrinking space for human rights protection in London, Copenhagen and Berlin

Only a few years ago, offshore immigration policies – the idea of shifting the responsibility of processing asylum claims to a different country – were considered an idea only palatable among the populist far right.

Now, on the brink of unfolding climate emergency and in the midst of a war at Europe’s border, countries are recanting their obligations under international human rights law and pushing for policies that take people who seek asylum out of sight and over the border. In this context, shado mag and Unbias the News present a collaborative investigative series into how these policies are affecting activists and communities that stand for freedom of movement and the right to refuge.

Back in May, activist and Reclaim the Sea founder Tigs Louis-Puttick woke up to a video of the Bibby Stockholm arriving in Falmouth. The Home Office announced plans to house 500 “asylum seekers” on the 222-dorm barge only a month earlier.

“I was just appalled,” Tigs told me. “I didn’t think it would actually happen – it was so preposterous that they would actually put people that have sea trauma on a barge.”

To relocate people seeking asylum into cramped accommodation where the waters are in constant sight is a particular form of psychological and physical violence. For many, these waters are a site (and reminder) of trauma, isolation, and suffering.

The barge was evacuated within days of onboarding people, after it emerged that Legionella bacteria was discovered in the vessel’s water system. Since then, government memos have revealed their intentions to hire more barges to relocate people seeking asylum, as well as disused RAF bases, prisons, student halls, and former office blocks.

I spoke to several grassroots migrant justice groups, legal support charities, and individuals about the impacts of offshore detention on immigrant communities based in the UK, and how grassroots resistance groups across the country are mobilising against the expansion of these increasingly carceral border policies.

Offshore Detention – inseparable from the Hostile Environment it emerged from

Although inhumane treatment of migrants and other racialised groups have been a mainstay of British history, when I sat down with Aliya Yule from Migrants Organise, her view was that the emergence of the Rwanda Plan and the Bibby Barge are not substantially separate from the existing Hostile Environment, but instead an “extension of and expansion of Britain’s border regime.”

Since 2012, there’s been a rapid acceleration and expansion of The Hostile Environment Policy introduced by Theresa May. This web of policies and legislation have effectively brought borders into every aspect of people’s lives, constraining how they have access to healthcare, housing, bank accounts, and more.

The government has exploited the public’s growing fears of financial insecurity during the cost of living crisis, blaming ‘economic’ migrants for crumbling public services. But the reality is that most if not all people seeking asylum are potentially subject to the same egregious living conditions and treated as criminals.

In fact, the introduction of the UK Illegal Migration Act in 2023 quite literally means that anyone arriving ‘irregularly’ in the UK will have their asylum claim deemed as ‘inadmissible.’ Criminalising people for seeking asylum contravenes Article 31(1) of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which explicitly establishes that governments cannot punish refugees for entering a country of asylum irregularly, because fleeing persecution or conflict often prevents them from accessing formal documents or safe and ‘legal’ routes.

The Home Office itself has admitted that there is “little to no evidence suggesting changes in a destination country’s policies have an impact on deterring people from leaving their countries of origin or travelling without valid permission.” Limited legal entry options are available in the first place, with even fewer now due to recent policy interventions.

This same act also means that all ‘irregular’ people seeking asylum could potentially be deported to Rwanda for processing of their claims – as solidified in the £120 million Migration and Economic Development Partnership deal the UK signed with Rwanda in April 2022.

Although last year the ECHR intervened to block the first Rwanda flights, it’s clear the Home Office is still pressing on. They’ve even recently announced a potential plan B if their appeal to the Rwanda Deportation Ruling is not successful – sending people to the extremely isolated and remote Ascension Island.

We are also witnessing an evolution of what we recognise as immigration detention, beyond the traditional ‘removal centre’ walls. The All Party Parliamentary Group on Immigration Detention’s 2021 Inquiry contradicts the government’s claims that moving people to barges, army barracks, or hotels are more humane alternatives, describing these locations as sites of ‘Quasi-detention.’

Visible security measures, surveillance, shared living quarters, reduced levels of privacy and access to healthcare, legal advice, and means of communication, and isolation from the wider community were all cited as common aspects of these large scale and institutional settings, which in effect replicate the conditions of incarceration.

One begins to ask, what is the desired impact of these actions if they are often revealed to be costly, impracticable, and riddled with operational difficulties? And more concerningly, how is this compounded uncertainty impacting the wider migrant community?

Instilling fear by design

Colette Batten Turner, founder of Conversation over Borders, brings together displaced people for English language classes, befriending programmes and online wellbeing peer support to reduce social isolation.

Since hearing about the Rwanda Plan and Bibby Stockholm, she notes that amongst the people they support, “the increase in suicide attempts is astronomical and the amount of safeguarding concerns that have been raised to us have skyrocketed.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Complex PTSD is one of the most common mental health conditions affecting people who seek asylum in the UK and this is exacerbated when people are put into situations that they find triggering of the trauma they have experienced.

Testimonies from residents at ‘quasi-detention’ sites in Napier and Penally from the APPG inquiry report evidence these concerns. One detainee in Napier recalled how fear overwhelmed them upon arrival, saying “the design of the camp was oppressive… it reminded me of the military camps in [my home country].”

Another Napier detainee stated “It’s like being in a psychiatric hospital… there are people rapidly becoming more and more mentally unwell around you, one has just tried to kill himself, another is in pain, another is very stressed and cannot cope.”

A September 2020 Equality Impact Assessment carried out by the Home Office revealed political motives behind these conditions, stating that “the need to control immigration” was the underlying reasoning for the “less generous” accommodation provided for people seeking asylum.

Beyond the traumatisation caused and exacerbated by actually living in these sites of incarceration, Colette points to the fact that “even without receiving the letter from the Home Office that says they are being sent away, the threat of being deported is enough to send most people into a complete downward spiral of mental health.”

This sense of constant fear and uncertainty is also compounded by the exclusion of people seeking asylum from government housing policies. There are ongoing discussions in the migration sector about the need to increase groups’ practical support as well as wellbeing offering, especially as increased numbers of refugees are effectively being made homeless by the latest immigration policy developments which withdraw their financial support.

Disproportionate impacts on LGBTQI+ communities and political refugees

Another aspect of fear around this system of quasi detention, offshore incarceration and deportations, is the disproportionate impact these policies will have on LGBTQI+ communities and political refugees.

In recent years, although total UK asylum applications have increased by 36% between 2019 and 2021, there was a 77% decrease in applications lodged in the UK where sexual orientation formed part of the basis for the claim over the same time period. According to the government’s own published national statistics in 2021, only 1% of all asylum applications were ‘LGB’ applications.

Legislative changes are directly impacting LGBTQI+ peoples’ ability to make asylum applications, creating procedural barriers which require people to take increased risk to their livelihoods to make claims. For instance, Section 32 of the 2022 Nationality and Borders Act makes changes to the existing standard of proof required from applicants.

Requiring individuals to provide ‘full proof’ of their fear of persecution at the first point of application immediately stacks the odds against people fleeing based on their identity, potentially re-traumatises them through incredibly invasive questions, and reveals a culture of distrust in a system that is already actively hostile.

“The introduction most recently of the Illegal Migration Act means that the UK is basically making it impossible for people to claim asylum on the basis of their sexuality or gender identity,” Colette explains.

This is especially difficult when the persecution refugees face is both state-sanctioned and interpersonal, making their lived experiences of discrimination harder to prove and visibilise. Applicants are expected to provide references, quotes, and contact details of people they have had romantic or sexual relationships with in their country of origin.

There are still 11 countries in the world where you can face the death penalty for being gay, and 70 countries across the world where homosexuality is criminalised.

If deportation to your country of origin means facing the threat of death, what would incentivise you to collect and provide evidence of your sexual orientation or gender identity to a government? Since 2017, the Tory government has sent 3,071 LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum back to countries where homosexuality is criminalised.

Even if their rights are protected on paper in certain countries, LGBTQI+ people often still experience high levels of discrimination and harm. For instance, LGBTQI+ rights charity Rainbow Migration cites widespread evidence of human rights abuses and discrimination against LGBTQI+ communities in the country of Rwanda, despite homosexuality being legal there.

The separation of LGBTQI+ refugees from vital psychosocial support networks and legal aid by relocating them to hostile countries like Rwanda and isolating them through quasi-detention methods like the Bibby floating prison is particularly detrimental to their mental health and freedom.

Colonialism, continued

The discrimination against LGBTQI+ refugees also requires an intersectional and decolonial analysis, especially given the fact that a majority of the people that these groups support are from Global South countries formerly colonised by the British Empire.

The UK and EU’s own past and present foreign policies have directly contributed to the persecution of LGBTQI+ people as well as other communities in these countries, which is now causing them to seek asylum. In more contemporary times, we have the 2017 Italy-Libya agreement, which provides the Libyan coastguard with financial support and technical assets to ‘manage’ its refugee population and prevent them from attempting to cross the sea.

An alliance of individuals and organisations known as Solidarity with Refugees in Libya has repeatedly spoken out about individuals being arbitrarily detained, tortured, and sold as slaves in these Libyan detention centres.

One of the members of the network, Eritrean refugee Abraham, noted that the UK’s expanding offshore detention regime has a particularly big impact on people from Sudan, Syria, Afghanistan, and Eritrea – particularly because they live under fear of dictator regimes back home.

“People in Eritrea are shocked about this news because they considered the UK to be a big and hospitable country,” Abraham explains. “What I’m seeing in the Eritrean community in England is that the people are suffering because they don’t know their future as the government gives different statements everyday, many people kill themselves.”

With its involvement in the harm of racialised people spanning over past and present, the UK government’s decision to contract the Bibby Stockholm barge as part of its wider offshore detention plan symbolises continued dehumanisation of ‘others’ in this country. Whether intentional or not, it’s a signal to refugees and folks seeking asylum that they are neither welcome nor safe here.

Start where you are, and move together

So what do grassroots groups see on the horizon for the future of offshore detention and migration policy in the UK, and how are they planning to resist?

Although disproportionate impact on particular immigrant communities has been highlighted as a result of offshore detention expansion, at the end of the day almost all racialised people are impacted by this hostile regime regardless of their current immigration status. Clause 9 of the Immigration Act now exempts the Government from having to give notice of a decision to deprive a person of citizenship. “So now,” explains Aliya, “anyone who is racialised in this country or othered has become vulnerable to state violence through the immigration system by weaponising the ability to strip them of their citizenship status.”

Reflecting on the need to demystify community organising and activism as something that is not only for certain types of people, Colette suggests: “what’s needed is for people to feel empowered enough to take action within the realm of their skills and experience, doing something that already aligns with their skills and interests.” It’s not so much about everybody becoming a full time activist and reinventing the wheel, but offering what you can to others engaged on the front lines and even behind the scenes to support them.

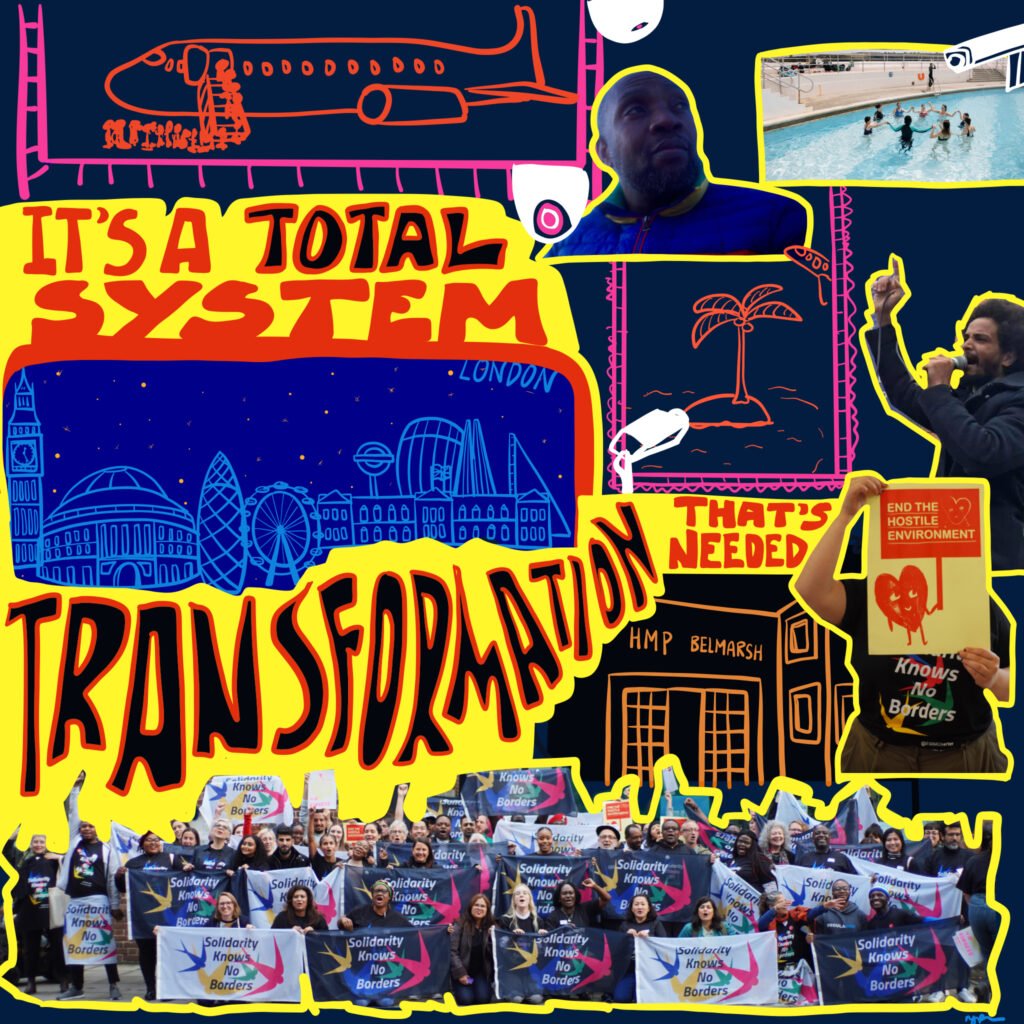

“We also need to stop asking for concessions for particular groups of vulnerable people,” Aliya adds. “We must really be strong and comprehensive in our understanding that it’s a total system transformation that we need.” A universal theme amongst all conversations as part of this investigation was that there is a timely need for us to collectively connect the organising and direct action aspect of our movements with mutual aid. People can’t organise against a system unless they can physically survive.

While Offshore Detention does not appear to be coming off the government’s agenda anytime soon, it is clear that the energy and focus needed to oppose these policies is in the room, and across the country with us now.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe, www.journalismfund.eu

What can you do?

- Write to your MP to Say NO to Floating Prisons for Asylum-Seekers – template letter here.

- Donate to Reclaim The Sea’s 2023 programme to help them enable people with sea-related trauma to reclaim the sea as a safe space through swimming, surfing, and paddleboarding lessons.

- Read this open letter to learn more about the alleged historical ties between the Bibby Line Group (the parent company that owns the Bibby Stockholm barge) and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. (spoiler: BLG’s founder John Bibby has been listed as co-owner of three slaving ships).

- Enrol in Corporate Watch’s free online Know Your Enemy: Practical Research Training, which will equip you with a wide range of investigative research tools for in-depth analysis of companies/industries complicit in the Offshore Detention regime.

- Donate your old phone, tablet, or laptop to Conversation Over Borders, where they can give them a new lease of life by redistributing them to refugees or people seeking asylum without access to tech. And while you’re at it, check out their English & Befriending and Wellbeing Support groups.

- Vote in council elections and get involved in local politics! Plans to dock barges near Liverpool, Edinburgh, and London have been successfully denied when met with local resistance – from community organisations, councillors, and even MPs.

- Sign this petition to end LGBTQI+ detention

- Share, circulate, and amplify open letters and legal challenges from national organisations and Unions speaking out against the government’s hostile border policies.

- For example, Migrants Organise has announced it is seeking to raise a legal challenge against the Home Office’s use of the Bibby Stockholm barge as asylum support accommodation.

- The Fire Brigades Union has also published a letter to Suella Braverman addressing safety concerns on the Bibby Stockholm, stating that “fire does not discriminate and therefore neither should safety regulations.”