Sometime in November of 2024, I was walking down Beirut’s Hamra street. The pavements were damp with rain water and cold air moved through the city’s alleyways. To my left, customers sat on colourful seats among the outdoor tables of a restaurant, and to my right was the entrance to an argile (shisha) café, with plastic chairs spilling out onto the sidewalk.

I’d just glimpsed at the men sitting on those chairs when a wave of crackling, electric bolts burst above our head through the sky. A loud bang echoed, and everyone looked up.

Our eyes returned from the sky and searched to meet one another; short glances between the restaurant guests, the men with their argile still in hand, and myself in between. “Was that a bomb or lighting?” a young man asked, visibly scared. An older man held my gaze as I continued my walk without a visible flinch. “No, no, this is lighting,” he reassured the younger man.

I often revisit this moment.

It was not lightning. Israel had just bombed Mar Elias, less than 4km away. Most people living in Lebanon are now attuned to the different frequencies of loud noises – is it mother nature? Or is it Israel’s sonic boom – or is it a bomb? During these winter months, we collectively learned to distinguish the sounds we heard.

The dialogue running through my head was relentless. “This is a bomb, where did it land? I hope my friend is okay… Oh, this bomb is not as loud as yesterday’s, but it’s much closer in distance. Two bursts mean it’s a sonic boom… Okay, so apparently there are different types of bombs, and they sound… different… Israel bombed Mar Elias with a rocket, it explains the crackling sound in the sky… that’s why it was not as loud as the bombs they dropped on Dahye.”

I can still hear the bombs Israel dropped on Dahye’s suburbs pulsing through my body. The bombs themselves are sudden, instantaneously permeating shockwaves. The mind does not process their memory beyond the trauma held in the body. The experience of a bomb is mostly in its aftershock as the body attempts to comprehend it.

I often wish I was big enough to flick their planes with my fingertips, to be strong enough to stop a bomb from shredding our neighbourhoods and our bodies.

But Israel’s material power does not stop at its industrialised military complex. It extends to an imperial hold on global and nation-wide media production hierarchies, which enforces itself on our worldly perception.

This power-hold seeps into every aspect of our reality.

Subliminal censorship: divide and conquer

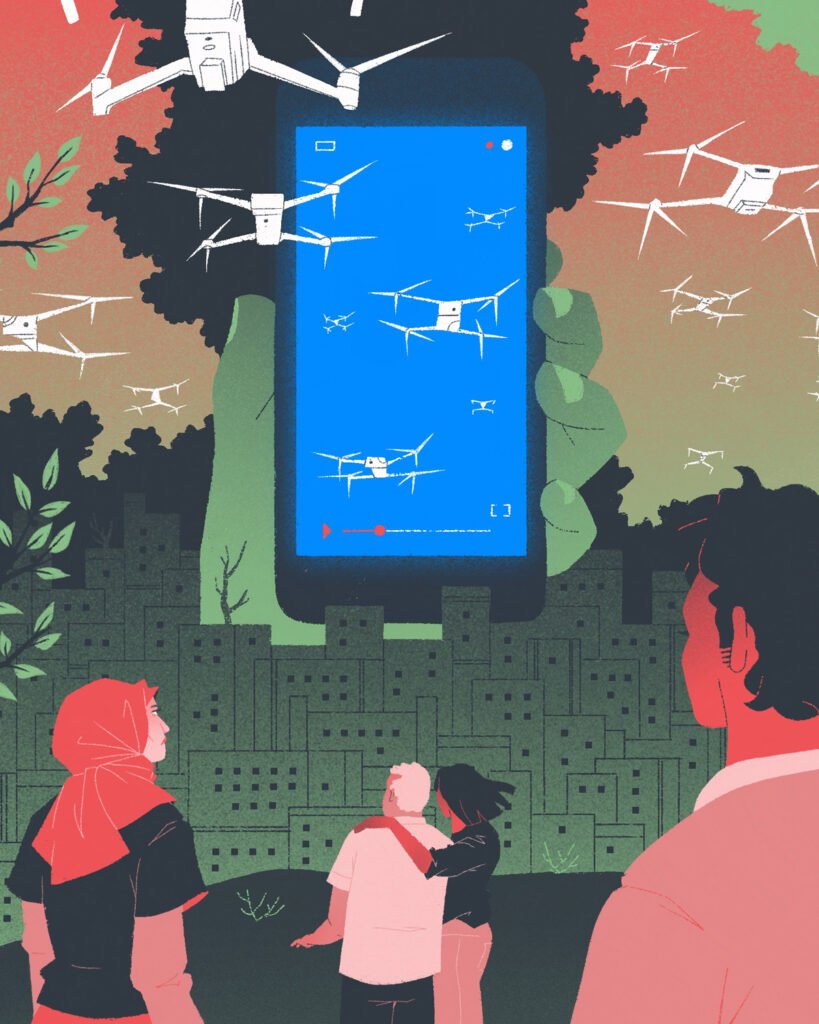

An Israeli drone was buzzing into my ears every hour of every day for months. They permeated every aspect of my being through mass waves of psychological torture to the point of paranoid thoughts.

My mind rushed to find meaning in how the sonic blasts synchronised with my activities. “I was writing about Palestine when it happened. They know everything about me. I texted a friend in Gaza before the bomb dropped. They have access to all the data on my phone.”

Before I knew it, I was festered with internalised oppression. In fear of my Palestinian identity, I began policing my own language, forbidding the slightest exclamation of rage to prioritise the politics of appeal.

I found it in myself to walk that same street in Mar Elias a month later. It was still charcoaled black, with three destroyed cars left unmoved. A public bench remained – I remember sitting there a few years ago, having a conversation with my friend – but the building it used to face was now an enormous hollow cave of rubble. There were the remains of an ice-cream parlour, which had opened its doors less than a week before its destruction.

I walked without pause; the waves of adrenaline soaring through my body no longer had the power to cause a reaction from me.

I began reflecting on why I walked that day, without a flinch. The truth of the matter is that no media coverage I’ve consumed since Israel’s genocide on Gaza – and its extension to Lebanon – has equipped me with the emotional readiness to react in a way that contains my humanity.

Mainstream media, both locally in Lebanon and internationally, has only distorted my reality. People talk of media complicity – and I have seen this to be true. I have witnessed the ways in which the colonial war on the Arab region is multi-dimensional, and the media is its strongest weapon.

Warzone framing

For decades now, the Zionist settler colony has devastated Palestine and Lebanon’s sovereignty; it has obliterated schools, universities, hospitals, airports, and entire cities and villages through its short history.

Since Israel launched its genocidal plan on Gaza, effectively turning a city conglomerate into a mass slaughterhouse, I watched the news each day in anticipation of what’s next. Until its brutality reached Beirut, where I live.

Once the bombs started dropping, it crescively began to feel as though the distant bomb knocked me off course and the international news headline stabbed me.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

“Beep Beep Boom! 2,800 Hezbollah terrorists hit by exploding pager plot” declared the front page of The New York Post, upholding a global celebration of American terrorism.

My balcony overlooks a hotel that housed displaced families from the South. Each room housed an entire family. Each morning, I would share a silent, distant cigarette with a young man, whose eyes were covered in white gauze, and his distraught elderly mother.

The headline is an epitomic representation of western society’s collective dissonance to its exploited global counterparts, upholding perceptions that reflect nothing of our collective reality in Lebanon and Palestine.

Media as a tool of undermining

Israel’s genocidal psychosis effectively left Lebanon in shambles. 1.6 million were displaced from southern villages and cities, thousands wounded among thousands killed. Following Israel’s military assault on Lebanon, the displaced quite literally had nowhere to go.

Hamra’s hotels were flooded with families; people of all ages were sleeping on the floor of public-schools-turned-shelters and abandoned buildings. A drive around central Beirut was marked by scenes of dozens of families sleeping on the streets.

I was sitting on that same balcony when four Israeli warplanes raced Beirut’s sky. Israel invaded Lebanon’s airspace in a habitual force of domination. It was the day people gathered to grieve Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah’s martyrdom.

He was assassinated 14km away from where I stood. To say that the 2,000-pound bomb Israel had used to violate Beirut that day had shaken through the entire core of my being is an understatement. Israel effectively razed six high-floor residential buildings into a 16-floor deep crater underground.

But in international headlines, our human essence is converted to sensational cases of pity amidst distorted schemas of vague dangers.

The disregard of our sovereignty and humanity in reported media about Lebanon trickles down into our everyday realities. After every aggression, students and workers across Lebanon were expected to resume their studies and work shifts immediately. It has reached a point where Israel’s aggressions in the South don’t even make it to local mainstream media streams.

If Israel’s brutality was “big enough” to cause nationwide panic – then we would have a national day off. This left people trapped in panicked binary thinking and inability to fully comprehend one another’s states of mourning.

Media warfare as cognitive battlegrounds

Palestinian journalists have completely re-defined the meaning of journalism – bypassing decades of dehumanising propaganda and challenging Western double standards. This has made Palestine a vanguard of global intersectional solidarity.

Yet, the counter-narratives that Gaza’s journalists, diaspora activists, and Palestinian academics have been tirelessly producing for decades are basically non-existent in Lebanon. Any framing that showcases the socio-political intersectionality between Palestine and Lebanon continues to be structurally censored.

In Lebanon’s political landscape, Gaza is understood only through a polarity of fragmented solidarity and othering. While Israel’s fascist politicians chant to turn Beirut into another Gaza, grasping the full scope of Israel’s atrocities in Gaza is basically an impossible form of consciousness as a result of the media sphere.

In the time that I’ve written this article, more Lebanese villages such as Kfarkela have been completely destroyed, leaving nothing but rubble. Other Lebanese villages are still under Israeli occupation, with their inhabitants either banned from entry or heavily surveilled to the point of being chased by drones.

As long as Palestine is under Zionist occupation, Lebanon pays the price systematically and structurally. The intersectionality between Lebanon’s struggle under Israel’s hegemony with the occupation and siege in Palestine is eerily obvious, yet never fully conceived as a reality – this is not a coincidence, but an occupational strategy.

Erasure of Indigeneity

Today, our national integrity in Lebanon is hidden behind headlines about ceasefire negotiations and attacks with no perpetrator. Media frameworks give almost no regard to international law.

Israel’s continuous, unexplainable violations of ceasefire agreements is never touched on by western outlets, let alone offered any form of subjectivity to those experiencing it.

In local media, diplomacy is only highlighted to remedy nationwide fear. Rather than being an active agent of people-centered national communication – over the decades, news effectively turned into a repetitive echo-chamber of symbols and detached characters.

The accumulating piles of contradictory “diplomatic” (imperialist) decisions orchestrated by American actors in a performance of peace negotiations thrive on the instability created by the media sphere.

Media coverage portrays events in vacuum, erasing past and present history through shallow reporting. It’s as though our grandparents did not exist. Israel’s brutal shows of domination reflect nothing but neo-colonial rule.

The generation that our grandparents were born in was as polluted with western involvement as the earth is now with plastic waste. Every life path they took, alongside our parents, trickled down and diverged in generational anguish.

The moment I realised that I descend from those who set generational life-paths within the intersections of borders, viewing my homeland as a warzone became absolutely nonsensical.

I have been welcomed into the homes of Lebanese across its political spectrum with the same hospitality. How can the south of Lebanon be a buffer zone, when each of its trees were planted with the hands of its inhabitants? How can any Southern village be a warzone when it consists of family homes? It is only a warzone through the Western gaze, dressing itself in vague, foreign correspondences.

The current political landscape does not make space for the vast array of Indigenous human experience within the region. Our land holds so much more than what Israel and its Western allies have perpetuated and forced us to contend with.

The warzone framing of any part of Palestine and Lebanon experiencing Israel’s hegemony through brutal violations of international order is a misrepresentation of reality. The very fact that these notions exist in Lebanese media, completely alienating the subjectivity and national belonging of Lebanon’s Southern areas and Dahye suburbs, is a remnant of brutal colonial legacies.

Distorted sociopolitical landscapes: alternative media in Lebanon

The media-produced discourse remains in fragments of what academics call “contestable categories.” It’s either that we the colonised discuss our history while holding western influence as a supreme historical initiation into “order,” or a model of modernity to morph ourselves into.

The moment the discourse moves into the west, we are spoken about as if we have no sense of autonomy. On the ground in Lebanon, locals translate an exotic, authentically broken image to the western visitor to sustain what is left of our economy; tourism, survival, and the NGO-industrial complex.

Alternative western-funded media outlets propagate “neutral” political analysis for young audiences that subliminally demonises resistance movements through repetition. The same west-dependent complex propagated shallow observations in reports; the discourse was “marked by sectarian division.” The human experience within Lebanon’s socio-political context is never explored any further.

It is in such a way that the very environment created by Israel’s brutalities, funded by its western allies, goes perfectly hand in hand with the waves of industries set forth to “develop” Lebanon through euro-centrist “democratic” values.

In other words, societal classes that benefit from the privileges brought upon by absolving Western-aided development perpetuate desensitised, blame-shifting frameworks. When met with another class’s mourning and rightful outrage, they speak of sectarian divisions.

It is very rare that we see any discourse revolving Palestinian or Lebanese resistance movements that involves itself with the nuances of our national history with colonial rule and the power asymmetry left behind by settler-colonialism.

En masse, these media formations turn into the modern equivalent of orientalist paintings depicting the ‘East’ – effectively weaving fantasy curtains of alienation. Behind the same curtain was the 1939 Fallahi (Indigenous farmers) revolution in Palestine, covered by frameworks of “Empty land”, “Bedouins and Berbers”, and “deserts.” The same occurred with the intifada; with “suicide-bombers” as the scapegoated common enemy. The media has constructed our ‘Otherness’ for decades.

Collective memory-making

To come across community-based journalism in Lebanon is a rare phenomenon. Our national tragedies have been reduced to body counts of martyred and wounded scattered in vague geographical locations to be swept away through the course of time.

If Lebanese alternative media relies solely on the support of Western institutions, how could the class operating within it produce a narrative that represents Lebanon’s people in unified interest rather than indoctrinate them?

Media in its current form is an imperial tool yet, it can still be used to see through collective memories. It is time that the Lebanese and Palestinians rebuild what colonialism has burnt down – leveraging media as a tool to educate, preserve memory, and connect through intersectional solidarity. Only then, we can maneuver our politics in a way that reclaims our humanity.

What can you do?

Listen

- Preoccupation: A not so brief history of Palestine

- Edward W. Said discusses Palestine, history of and struggles in the Middle East

- Rafeef Ziadah – ‘We teach life, sir’, a poem about media complicity.

Watch

- Courses Archive – Makan

- Mohammed El-Kurd on the media’s complicity in genocide, where he dissects media complicity and the politics of appeal.

- Free Palestine TV produces field-reporting on Israel’s aggressions in Lebanon. It’s an independent local alternative media platform whose content showcases Lebanese and Palestinian testimonials and perspectives at the centre. It also produces informative content with Southern Lebanese lived realities and perspectives.

Read

- How settler colonialism became innate to the imperial psyche

- What is Settler Colonialism?

- Ghassan Kanafani’s ‘On Zionist Literature’: A vital critique

- Racial Legacies by Fanny Brewster and Helen Morgan

Discover

- Humans Of Dahieh 🇱🇧 showcases daily life in Dahye. They produce media that counters the dehumanization of Lebanese Shi’ites and on-ground reporting that centers the human experience.

- We Are Not Numbers

- NewsCord