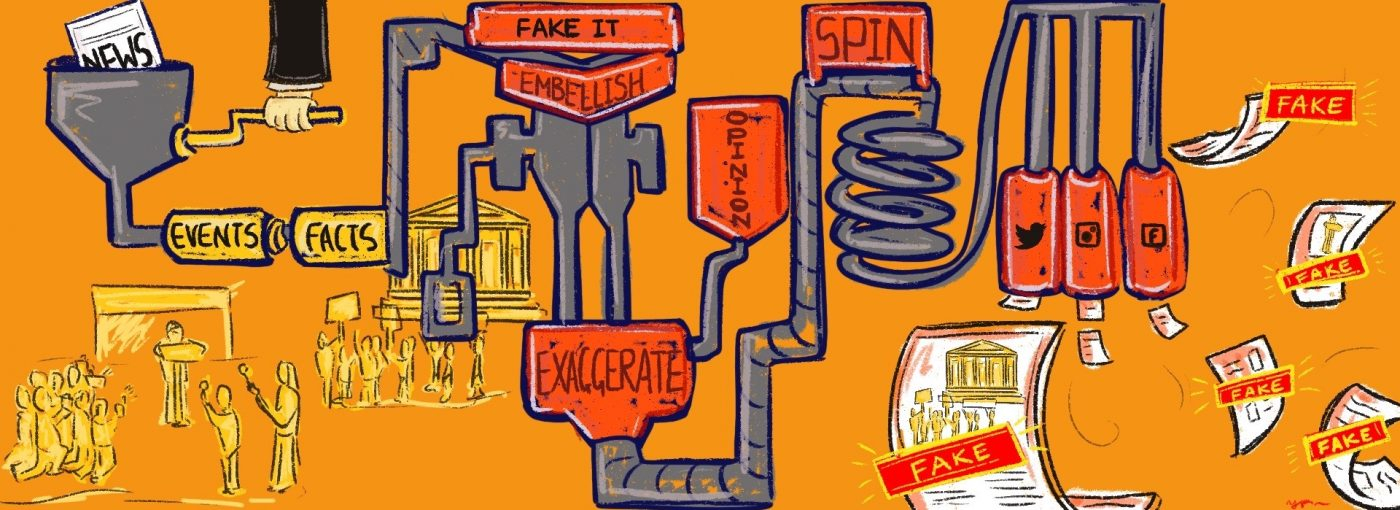

‘Fake news’ is a term which has become unnervingly commonplace in our popular lexicon. Its implied definition and use – one of spotting misinformation and exposing it – can be a useful tool for protecting the public from the harms of false narratives. Uncovering fake news is often pursued by individuals or groups with an interest in democratising public life and the movement of free information. Yet due to the prevalence of social media as part of the fake news discourse and the undeniable toxicity of our political environment, the term has become much more nebulous, as it has been adopted by various governments as an excuse to clamp down on legitimate criticism of their regimes. Through this top-down understanding of the term, we can view fake news as the newest evolution of manufacturing consent.

Though heavily associated with the Trump era due to the former President’s abuse and misuse of the term, to the point of even comically launching ‘Fake News awards’, its origins stretch back as far as political life does. Simply put, if a political system entrenches power, it rewards charlatans who can game the system. If the same people, normally from a similar background, keep returning to power then the system looks visibly rigged to everyone else, fostering mistrust in the whole political order and less public participation. The ruling class therefore has a material interest in allowing such political apathy to seethe, as disinterest or dissolution allows them to maintain dominance. The control of information is an important tool in sustaining power, so media platforms unsympathetic to those at the top are treated with suspicion and outright hostility. This is where the newest iterations of fake news come in – a means for those in power to create misleading narratives which lessen the consequences of their own actions.

Hence fake news has become, perhaps always was to some extent, such a loaded term. It has taken on so many meanings with various implications that is only understandable when looking at how the term is utilised and, vitally, who it is used by. If charges of fake news come from the top, its origins lie in the same power dynamic which has kept the ruling classes in power for centuries, in various forms around the world. Fake news is thus conceived as an accusation, an implied stain on critiques of power. This is proven by the host of unsavoury leaders which have frequently abused the term, from Donald Trump in the US to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. With their use, the phrase loses any semblance of public good, instead functioning as a defence mechanism and means of control for some of the most corrupt and repressive governments.

It is worth looking deeper into particular cases, such as Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, to gauge the real scale of fake news being used as a cover for oppressive policies. Prime Minister Orbán has long been an enemy of civil liberties, demonising Hungary’s LGBTQI+ residents by seeking to ban same-sex adoption and end legal recognition of transgender people, as well as scapegoating migrants as a “poison”. COVID-19c has added a new dimension to the far-right leader’s divide and rule tactics. Adopting a state of emergency early on, Orbán moved to allow ruling by decree in an supposed effort to handle the virus. This allowed his party ‘Fidesz’ to push their authority to new limits under claims they were tackling the scourge of fake news during the public health panic.

One can easily see how the extreme far-right leader, content on suspending safe asylum laws for similar reasons, would take advantage of the pandemic and the admittedly real issue of misinformation. This has come in the form of curtailing press freedom, which has been battered in Hungary for years to the point it is now largely state-run or state-sympathetic. Damningly, Fidesz sought the ability to jail journalists for up to five years for purposefully vague crimes of spreading falsities. This attempt to silence journalists is already having profound consequences. The chief editor of one of the country’s few remaining independent media organisations, Index, was sacked, with ruling-party fingerprints all over the action.. This violation of press freedom was met with large protests in Budapest, but Orbán did not back down in cementing what is now effectively a state media monopoly.

The fluid terming of fake news helped make this possible. Orbán, in power for a decade, has sought to present fake news as damaging to Hungarian society, and claims to tackle it through highly invasive press interference, market manipulation and delegitimising government-critical journalists. The pandemic has allowed this process to be ramped up, with any objection to the government’s handling of COVID-19 being tarred as fake news that undermines public health. Thus, Orbán has secured an authoritarian grip of the fake news mantle in Hungary, using it as a weapon to silence arguments which run counter to the official state narrative.

Fake news only means what the regime wants it to mean – we have surpassed genuine concerns about the public being misled and moved into the realm of information control.

This is part of a worrying trend of governments using fake news concerns as masks for punishing internal dissent. In Central Asia too, autocratic governments of the region have been similarly keen to police media spaces in an even greater capacity. In June 2020, Tajikistan’s President Emomali Rahmon introduced amendments to existing laws which empowered the government to directly tackle fake news around the COVID-19 pandemic. This included large fines and jail time for the vague offences of disseminating false information. Although it is yet to be concluded whether this measure has increased arrests, the power it has to enact arbitrary repression and expand existing censorship in the country is chilling. Without clear guidance on how the government will ascertain how false any piece of information is, the law is rife for abuse by the authorities, with the very real potential to further harass journalists and curtail freedom of assembly and protest.

Similarly, in Uzbekistan the pandemic has created a situation where emergency measures can be pushed through, limiting freedom of speech in conjunction with other rules such as temporary confiscation of mobile phones for those isolated in quarantine wards. Civil liberties have been suffering at the hands of authorities eager not to lose face during the health crisis but also exercise control of information as a guise for tackling fake news. Kyrgyzstan almost passed an even more draconian law regarding the ‘manipulation of information’, which would have allowed the authorities to shut down access to websites promoting ‘false information’. Going further, it had the potential to make online anonymity punishable and force internet service providers to allow government access to user data. It is speculated that the only reason President Sooronbay Jeenbekov sent the bill back to parliament for revision is due to a need for the government to avoid extra scrutiny on civil rights after Kyrgyz activist Azimjan Askarov died in police custody in July 2020.

The irony of all this is that many of fake news’ greatest opponents have promoted actual falsities to secure their grip on power. There have been patterns of distorting events and fabricating national statistics, as well as circulating false stories to discredit political opponents. Coming from a place of authority, such tactics strengthen the ruling ideology and pave the way for destructive policies, such as Duterte falsely claiming that there are over four million drug addicts in the Philippines to fuel his authoritarian drug war.

This is evident too in Brazil, where far-right Bolsonaro’s election was fraught with social media spamming, encouraging homophobia and racism through shared WhatsApp stories. One tale that circulated claimed Bolsonaro’s opponents would introduce ‘gay packs’ into schools, amongst other bigoted lies. Floods of disinformation have plagued Brazil during the pandemic, where its numbers were some of the highest in the world, often downplaying the virus or, crucially, bolstering pro-Bolsonaro support. The most morally bankrupt leaders are hyper-critical of fake news when it targets their administration, but soft or even complicit in the dissemination of misinformation when it benefits their control. Spreading false information is not a problem if it has political advantages to the ruling class, which illustrates the utter contempt such leaders have for their own citizens in deceiving them this way.

What has followed the adoption of the term fake news by the ruling class is a complete dilution of its meaning. The range of situations where it can be apparently applied has allowed shrewd governments to attack free speech and political dissent under the guise of tackling this phenomenon. The number of countries which are enacting new laws that mention fake news or aim to stop its spread is growing, compacted by the COVID-19 crisis. But instead of countering misinformation by encouraging transparency and demanding higher journalistic standards, leaders have taken it upon themselves to censor and limit criticisms of the government, which often pointed to medical supply shortages and other failures as evidence of poor handling of the pandemic.

What unites such disparate countries is a shared desire to crack down on dissent, riding the wave of attention and power that the nebulous term has garnered in the past few years. In our hypernormalised world, the fact that fake news is mixed in with genuine critiques of authoritarian governments is alarming. This has set a trend for governments worldwide to punish their own citizens in the name of fighting this unconquerable beast. Conclusively, persecuting instances of fake news is about stifling opposition to prevailing orthodoxy instead of a genuine need to tackle the misinformation crisis. The ruling classes do not accept narratives which harm their power, only eager to tackle the kind of news that they view as a disruption to their order. Unscrupulous leaders will always have a reason to police certain speech; it would be wise to keep this in mind whenever the term fake news is bandied about by those who wield power.

See more of Natasha’s work on instagram