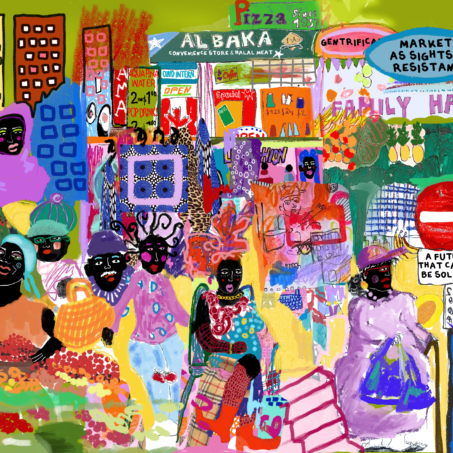

“Inserting the people who you want to be in community with, into your work is a really concrete political act in the sense that you can bring people together in a very beautiful way,” British-Bengali visual artist and writer Mohammed Z Rahman says to me as we catch up over Zoom.

Through illustrations, painting, zines, short stories, essays and more, Mohammed explores and interrogates socio-political and personal histories, and meditates on themes of identity, home, community and more. Exploring their catalogue feels both imaginative and familiar – particularly as a second-generation immigrant myself – as a disruption of pervasive power structures that allows space for collective dreaming.

During the conversation, we share our ambivalence with social sciences and academia, the urgency of cross-community solidarity, and the ways in which art can help us build it. Feeling disillusioned in the current global political landscape and strangely disconnected from my own diasporic community, I didn’t know that a conversation with Mohammed was exactly what I needed to feel re-energised, grounded, and most of all, hopeful for the future.

Growing up in East London as the child of first generation Bangladeshi parents, Mohammed has been surrounded by the art of making for as long as he can remember. Housing was precarious, as was employment, which meant his childhood was punctuated by displacement and resettlement. His mother, aunts and sisters utilised their inherited crafts from living in Bangladesh to make their new digs feel like home – basketry, weaving, embroidery, furniture building and more.

Mohammed reflected on how his domestic art at home didn’t seem to hold the same ascribed societal prestige as other forms of commercialised art.

“When you don’t have things and you can’t buy things, you make and you repair things you already have. Growing up, there was a very utilitarian slant on it, which I only think in retrospect, was very kind of embodied and not very [socially] valued,” he explains.

These early experiences are why you’ll often see Mohammed process identity through an intimate portrayal of the domestic through material culture: food left out on the table, a child watching TV, three women sewing and embroidering together. Mohammed’s work prompts me to reflect back on the role of the home in my own childhood. How it was so often the quiet moments in between that I remember most. In waiting for my parents to come home from work, finding innocuous ways to pass time with my siblings,

Artistic expression as activism

Partway through his social anthropology degree, Mohammed started making zines as a tangible antidote to the wordy, white-washed obfuscation of migrant histories that so often permeates into the academic structure.

Our frustrations in the world of social sciences were similar, there’s a sort of disembodiment and alienation that comes when people are reduced down to purely ideas and thought exercises. It was a feeling I knew all too well studying sociology in university, myself. I remember sitting through lessons where white students dominated spirited discussions about race, and listening while some professors facilitated debates that sought to justify and understand imperialism and spoke curiously on the harm inflicted on ‘brown bodies’, rather than people.

The role of privilege and access in academic institutions became starkly apparent as well. As a person from a working-class migrant background, Mohammed was able to learn more about Bangladeshi history both broadly and specific to East London in uni. They think back to a penny drop moment in an anthropology of South Asia course, where they read a paper about their people, the Bangladeshi diaspora in East London written by an affluent, white academic.

The experience made them painfully aware of how historical information is gatekept through language, location and class. Sifting through complex histories is emotionally taxing itself which was then compounded with the realisation that so many in their parents’ generation wouldn’t be able to engage with this depth of historical information.

“I’d never had access to that kind of detailed information about my people and my background, and it’s about my parents’ generation. But I know, for all these access reasons, they wouldn’t ever be able to read it – and it was really emotionally complicated to do that,” they recount.

Mohammed’s work is also influenced by the immense cultural production that came out of the Independence of Bangladesh in December of 1971. In the eight months leading to independence, Bangladesh suffered a brutal and violent genocide of at least 3 million people at the hands of the Pakistani Armed Forces and allied militias, with immense support from the U.S. government by way of a lifted arms ban on Pakistan. The Bangladeshi Independence movement produced a wealth of art from literature, paintings, to films, documentaries and more.

Creating art and remaining politically engaged are ways we’ve both found productive in staying connected to the humanity of this work. He speaks with a reverence for emotionality in his work, it’s a necessity to be deeply moved by histories of resistance, discrimination and empowerment.

Instead of relying solely upon speaking the language of the institution in order to critique power structures, Mohammed seeks to breathe emotion into his art, weaving grounded personal narratives and imagery into his paintings and illustrations. Beyond the personal, art can give us the tools to connect individuals to social and cultural movements, and strengthen social movements laterally with each other.

“Intellectualising things has become a real sickness of the left. The way that we’re talking about, and trying to understand, issues – it’s not the same thing as taking to the streets and actively building a community with the people who are directly affected by the social issues we’re talking about,” he explains.

A visual piece, a silly, punchy zine or a short story have more power than you might think. Creation is an act of counter-writing histories and imagining new ones – building crucial momentum and resonance around social movements. This is reflected in Mohammed’s inspirations, too, citing Emory Douglas, the revolutionary artist with the Black Panthers, known for communicating the party’s message in the 1970s. “In the UK context, where I grew up there’s a lot of erasure, a lot of negative storytelling, a lot of propaganda really. It’s really important to assume political art, across geography [and] across time.”

I see those exact narrative pitfalls where I live, too – a suburb about an hour outside of Vancouver, Canada densely populated with one of the largest Sikh-Punjabi communities outside of Punjab. Like so many others, our community has so often had our story written for us, or about us in Canadian news media, pushing harmful stereotypes that reduce our identity down to our propensity to do crime, or our ability to be the perfect model minority.

Learning about social movements through the lens of political art has given me the ability to tease those stereotypes to see them for what they are – a failure to define what they never sought to know in the first place.

Our histories never existed in isolation

With increased access to resistance movements around the world via social media, it’s imperative that we think of our fights for liberation as interconnected. A point of frustration for both Mohammed and myself is the prevalence of uncritical and siloed ideas of what liberation really means.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

We see it with the increase in conservative South Asian politicians who use class-privilege to pedal racist and xenophobic rhetoric, in generations who grew up embedded in social justice movements in the 70s, speaking the language of nationalism and neglecting the intercultural solidarity that brought progress in the first place.

Mohammed believes that this thinking “works against intersectional and cross-cultural theories, and serves to form disempowered political projects that just kind of exist in isolation.” In actuality, they say, “there’s obviously been a migration of people, ideas, artistic practice forever, really.”

Thinking historically about activism is important, it grounds us and connects us to the broader context of our resistance. Uncritical perceptions of liberation are often born from what Mohammed calls a “generational amnesia,” that by not tapping into histories of organising, each successive generation feels like they’re reinventing the wheel, despite the fact that our communities have been organising for millenia.

I think back to histories of solidarity amongst Black and brown communities in the UK in the 1970s, fighting in intercultural communities for labour rights, racial justice, gender parity and so much more. Despite these histories of solidarity, there is a troubling level of enduring anti-blackness and prejudice within our community.

“[It] doesn’t really make any sense because these people and these histories have never really existed in isolation. We’ve been neighbours and have lived under the same kind of colonial legislation and oppression. There’s so much more that’s worth connecting and forming solidarity around.”

While access to archives about resistance movements aren’t always accessible, Mohammed talks about dreaming and documenting intercultural solidarity they’ve seen in their work as a way to actively disrupt colonial thinking.

The process of thoughtful artistic reimagining is a tool to destabilise the colonial project and take control of our own narratives, they explain. “I think there’s something so valuable in the archiving of people living with each other…forging and strengthening these solidarities across culture across generations, that’s really a much bigger threat to the persistence of inequality and injustice and erosion that exist.”

Connection and solidarity exist all around us, they’re entrenched in the histories of so many diasporic communities. When we’re told that advocacy for our community is zero sum, that it comes at the cost of not supporting other justice movements, we have to question where that exclusionary thinking came from and who it ultimately serves to benefit. And where we can’t immediately find it, we create it.

The whole process takes a lot of emotional work; sifting through histories, making sense of it all, and then dreaming up ideas and reformatting them in a way that feels curious, digestible and interrogative.

I spend a great deal of time dreaming. It’s essential to my own activism, a beacon of hope that our collective goals are achievable through the commitment to justice in all forms.

For Mohammed, inspiration can come at any moment and ideas are constantly mutating and changing form, as they mull over how to best express them. Our histories, like our identities, are in a constant state of becoming – never static, never monolithic.

Mohammed’s work reminds me of the power of dreaming, of turning to an embodied artistic practice as a form of activism and the commitment to cross-cultural solidarity. Our histories have always been interconnected, and our liberation will be, too.

What can you do?

- Check out Mohammed Z Rahman’s website and follow them on social media

- Try your hand at zine-making with this beginner’s guide

- Read: “Until dignity becomes a habit, we need cross movement solidarity”