Our world has been fundamentally transformed by COVID-19. Our vocabularies have expanded, our emissions have (very temporarily) reduced, and we’ve had to accessorise more than usual, while over 229 million people have been infected and over 4.7 million people have succumbed to the virus. Hundreds of millions of people have lost their homes, their jobs, and their loved ones. Some industries have halted, innovated, and evolved in response to pandemic conditions. Others have not. Some countries are now enjoying the privilege of opening up freely. Others are struggling to stay afloat.

Throughout the past two years, my mind has lingered on one industry that has refused to fundamentally change in any meaningful capacity in over a century. The factory called school. While every country has its unique scholastic quirks, the general model has remained fairly consistent over the decades. Not even a pandemic could shake things up, as the vestiges of colonial and industrial capitalist conceptions of schooling retain their stranglehold on education.

Despite the heightened stress, uncertainty, and anxiety of the pandemic, young people have been expected to maintain their ‘careers,’ logging on to online school every morning, turning on their cameras, sitting through exhausting lessons, and submitting their assignments, perhaps with slightly more flexible submission dates. And as the pandemic exposed, some children simply can’t access online schooling, due to their socioeconomic circumstances, so have been left to fall behind and slip through the cracks. Even before the pandemic, we’ve forced children and teenagers through early starts, long hours, rigorous exams, demanding assignments, and excessive regulation, robbing them of their curiosity and freedom. Why?

The legacy of school has been fairly ugly thus far, marked by the breaking of young spirits into the capitalist system, creating useful workers for the factories of industry. All by design. One of the fathers of state schooling (and German nationalism) Johann Fichte, argued that schools should be used to create a cohesive and compliant citizenry who would submit to the nation and the virtues of the State.

Prussian educational theorists created a schooling model built around centrally controlled curriculums. This included constant fragmentation of days, with changing classes signified by the sound of a bell which promoted obedience and teacher-directed classroom groupings. The father of scientific management, Frederick Winslow Taylor, outlined the purpose of schooling as follows:

- To increase the efficiency of the labourer, i.e. the pupil.

- To increase the quality of the product, i.e. the pupil.

- Thereby, to increase the amount of output and the value to the capitalist.

His ideas were adopted, interpreted, and applied by school administrators all over the world. Alexander Inglis, Assistant Professor of Education at Harvard University in the 1920s, reinforced the purpose of state schooling through six basic functions:

- The adaptive function, establishing fixed habits of reflexive obedience to arbitrary authority.

- The conformity function, producing compliant, predictable, and easily controllable masses.

- The diagnostic function, determining each student’s ‘proper role’ in society, based on their academic record.

- The differentiating function, sorting and training children for their designated role, and no further.

- The selective function, reinforcing hierarchies of superiority and inferiority to ‘improve the breeding stock’ by tagging the ‘unfit’ with poor grades, poor placement and punishments.

- The propaedeutic function, creating an elite group of children capable of propagating this system of dumbing down, declawing, and controlling the populace.

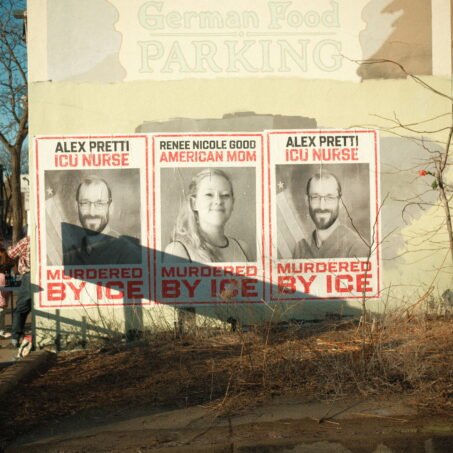

Schools have retained these primary functions through wars, revolutions and pandemics. Throughout the world, whether in former colonies or the heart of empire, they serve as tools of classism, racism, ableism, sexism, nationalism, statism, and other systems of oppression. Schools exist to maintain class- and race-based segregation; facilitate bullying and harassment on the basis of race, sexuality, or neurodivergence.

They do this by funnelling low-income students into further poverty, crime, and eventually prison; stripping Indigenous peoples of their cultures and lifestyles; penalising disabled children for missing school and learning differently; enabling rape culture through the pervasive regulation of bodies; and propagandise children to accept the virtues of a broken world.

By their fundamentally authoritarian nature, schools demand the submission of their students to the authorities, including the authority of the school bell itself. In many schools, children are expected to beg for permission for the simplest of behaviours, including drinking water and using the bathroom. We’ve accepted as normal that children should have little to no choice in their own learning. And when children do speak out against their conditions, they are punished, scorned, mocked, and told to grow up. “Everyone goes through it,” people say, as though that were any excuse for the maintenance of a damaging and deeply unhealthy institution.

When children start school, they are self-guided, curious about the world they live in, and believe everything is possible. When they finish, they are cynical, miseducated, propagandised, and used to dedicating 40 hours of their week to an activity they never chose. And yet we force them to go anyway. Something needs to change. What currently exists is antithetical to actual learning. We need to abolish schools.

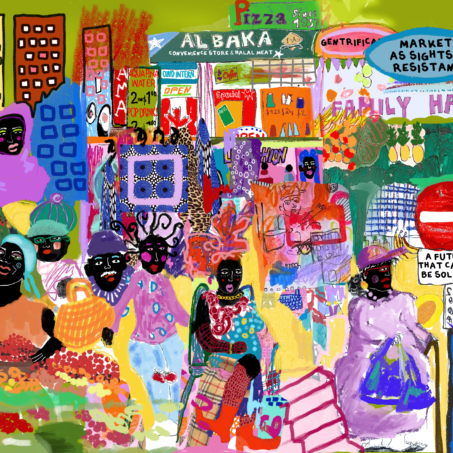

We need to free education from the grip of compulsory schooling. I understand the impulse to seek legislative reforms, but top-down solutions cannot solve the fundamental issue with the structure of schools, they can only reinforce it. No government or school board would willingly give up their total monopoly on indoctrination. This revolution of education requires a grassroots approach, allowing a multiplicity of learning styles to bloom across regions.

Children and teens need to take the reins of their own education, an education philosophy that already has a precedent in many parts of the world. Democratic, self-directed education (such as in Sudbury schools, where students and staff are equal citizens) afford students the freedom and responsibility to manage their own learning, with great success.

These philosophies and models recognise that truly fulfilling learning can only occur where there is trust, respect, and self-determination. They recognise that learning is a life-long journey, and we should prepare children to carry on that journey outside of the formal learning environment, equipping them with the tools they need to lead a balanced life.

But how can we get there? Students, teachers, and parents all have a role to play in seizing education from the grip of the state. While individual students may pursue unschooling and individual teachers may afford their students more freedom, a truly comprehensive transformation would require the organised efforts of autonomous students’ and teachers’ unions.

These sorts of grassroots organisations can strike, walkout, and wrest control from school boards and authorities in order to construct a more equitable and democratic system of education, without the restrictions of exams, homework, and curriculum. The fight won’t be easy, but we can’t carry on as we are. We need to break the cycle so that learning and freedom can flourish.