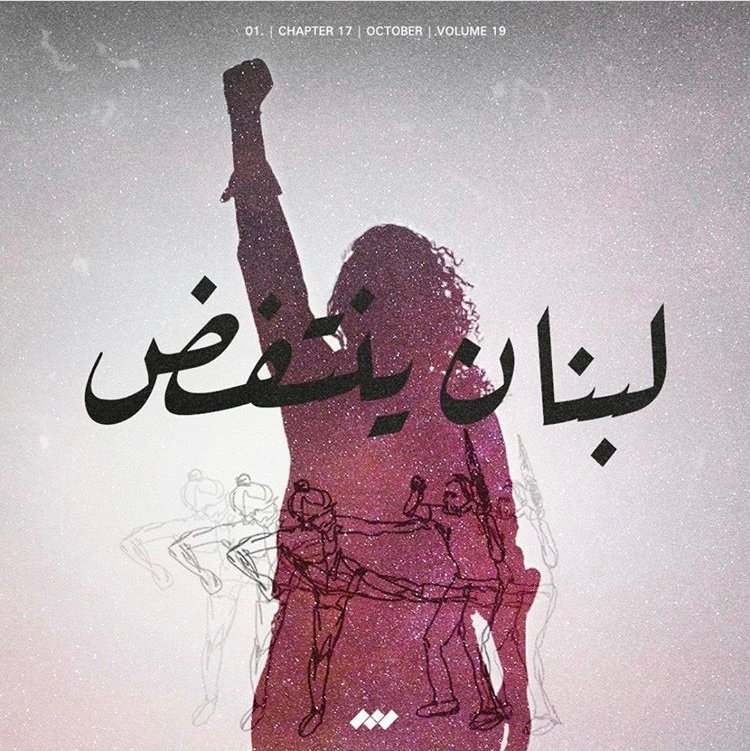

Ever since it erupted on the night of October 17th, the uprising in Lebanon has unleashed a wave of creativity that continues to rock the very foundations of Lebanese politics. Whether to express anger or joy, or somewhere in between, the chants have become a central point of unity. They are often created on the streets, improvised from scratch or adapted from a pre-existing chant or tune from Lebanon or the region.

HELA HELA

We start our exploration of the chants with the one that became the earliest unofficial anthem of the protests. It’s fairly explicit, and it goes like this: hela hela hela hela ho, Gebran Bassil [foreign minister] kess emmo. It translate as Gebran Bassil, fuck him (literally ‘fuck his mother’), and you can hear it here on the first night of the protests. The point really isn’t just to insult Gebran Bassil, but to degrade him so much as to make him symbolically equal to everyone else. In other words, being so ‘rude’ to politicians like him is part of the process facilitating the taking of the streets. Here, you have to understand that these warlords-oligarchs are usually addressed with honorifics to separate them from everyday people. Think of them as the equivalent of ‘your excellency’ in addition to those (like Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah) who have more overtly religious ones. The chant’s outrageous ‘catchiness’ lead to dozens of covers, including an opera one, a techno one, and even an instrumental ballad one. These all travel via WhatsApp and social media channels, and have been adopted by Lebanese in Lebanon and in the diaspora.

But given the misogynistic element to the hela hela song, other protesters have since reclaimed it. Feminists have, for example, replaced the second part with ayreh bi Gebran wa bi Aamo (“fuck Gebran and his father-in-law [the president]”; ayreh actually means “my penis”). This has been especially powerful as some other anti-Bassil chants have taken an extremely homophobic tone, despite the fact that Bassil is himself very homophobic, and so is his party the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM): as part of their disinformation campaigns against anti-government protesters, one FPM member even said on live television that the protesters want to bring down established religious norms in Lebanon, including promoting a secret gay agenda and ‘promote’ homosexuality. The feminist interpretation, in other words, focuses on the source of corruption, the politician, without throwing vulnerable groups like women and/or LGBTQ+ people under the bus. It is both a rejection of the individual politicians and of the patriarchal structures that are at the core of the sectarian system as a whole.

Furthermore, protesters blocking the ‘ring’ bridge for the past few days have changed the second part of the chant to el jisr msakkar ya helo (“the bridge is closed, oh handsome one”), with drivers joining in by honking. This has also been credited with transforming the more common road-related emotion, anger, into something more joyful. There have been videos of angry commuters getting out of their cars to join the fun (instead of honking and getting angry). By doing this, protesters are channeling the frustration felt by commuters everyday – Lebanon does not have public transportation, and traffic gets pretty bad – away from protesters and towards politicians. A simple chant is able to transform negative into positive energy, thereby helping maintain the momentum against the sectarian status quo.

As of today, one can still hear the original chant but it has since been replaced by much angrier ones.

KELLON YAANI KELLON

Kellon yaani kellon, “all of them means all of them”, has different versions, but the general idea is to add wa [name] wahad mennon, or “and [name] is one of them”. So, for example, wa Nasrallah wahad mennon, “and Nasrallah is one of them”. This became a hashtag in itself, with people (including yours truly) replying to pro-government users with customised kellon yaani kellon. A supporter of president Michel Aoun would get kellon yaani kellon, wa Aoun wahad mennon.

The message is simple and powerful: no politician can ride this revolutionary wave as it explicitly and pre-emptively excludes them all. In some ways, this has been the most effective chant so far. It denotes a complete and total rejection of the sectarian status quo, and firmly places blame on all politicians, no matter how high-ranking or low-ranking they are, who participates in it. Usually, supporters of sectarian parties try and separate their preferred leader from the rest, swearing by his (and it is always a he) honesty, his genuine desire to serve Lebanon only to be sabotaged by everyone else’s preferred leaders. Kellon yaani kellon leaves no doubt: they are all guilty, and they must all be held accountable.

So threatening has this chant been that Hezbollah supporters have even appropriated it, though rather awkwardly. Instead of saying wa [name] wahad mennon, they’ve been saying wa Nasrallah ashraf mennon (“and Nasrallah is more honourable than them”). Needless to say, it hasn’t really caught on. Hezbollah supporters have even taken footage from the protests and dubbed over their own song mish kellon abadan mish kellon (“not all of them, not all of them at all”) to make it look like Nasrallah is not one of the politicians opposed on the streets. This has been betrayed by Nasrallah himself, who waste no time in throwing his weight behind what is arguably the most unpopular government in recent history – no government has really been ‘popular’ in decades. Ironically, by doing so he only furthered protesters’ resolve to repeat kellon yaani kellon.

ASH-SHAB YURID ISAAT AN-NIZAM

The people want the downfall of the regime.”

This popular slogan first emerged during the Tunisian revolution of 2011 and has since been adopted throughout the Arabic-speaking parts of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), from Libya to Yemen, passing by Egypt, Bahrain, Syria and Iraq. In Lebanon however, it is not a single ruler who is the problem. There is no Assad or Mubarak/Sisi or Gaddafi/Haftar or King. The regime here is the sectarian regime, proposed up by a collection of warlords and/or oligarchs who benefit from it and benefit those around them. The closest system in another Arab-majority country is in Iraq, which has been seeing its own protesters, and has been facing much more brutal repression with extraordinary creativity and resilience.

While ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam has been chanted several times in previous protests in Lebanon since 2011, there has never been such a widespread acceptance of the slogan in a usually hesitant political culture. Up until now, the warlords and oligarchs have managed with relative success to pacify the population by comparing Lebanon to Syria or Libya or Iraq, the message being ‘if you continue, you’ll end up like them’. In recent weeks however, the proverbial wall of fear has been brought down, and protesters have been chanting ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam on a quasi-daily basis from northern Lebanon to southern Lebanon, passing by Beirut, the Mountains and the Bekaa valley. One of the most impressive manifestations of it has so far been in Tripoli, since dubbed the capital of the revolution, where tens of thousands chanted it on the night of October 22nd. It was prefaced with the message, “if they [the government] close all squares, you are all welcome in Noor [light] Square [main square in Tripoli]”. This has lead the Lebanese writer Elias Khoury to call Tripoli the light of the revolution. The most popular version of ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam is a song by veteran Lebanese hip hop artist Rayess Bek called thawra (revolution). Although originally created several years ago, Rayess Bek re-released it some days ago, no doubt responding to its popularity on the streets.

HAYOO [city/region name], HAYYEHA

Hayoo, or ‘hail!’, is a way of expressing solidarity with other parts of Lebanon, followed by hayyeha! as an affirmation. It follows the following format: hail [city/region], hail! One protester with a megaphone would say hayoo Beirut and the crowd would reply hayyeha! For example, in Tripoli, protesters could be heard repeating in their tens of thousands their calls for solidarity with others parts of Lebanon. Most notably, and this is unprecedented, protesters in Tripoli (which is a Sunni-majority city) sent their solidarity to Shia-majority areas of Lebanon such as Nabatiyeh and Dahieh, and vice versa from Nabatiyeh to Tripoli. Protesters in Beirut have also regularly used it, such as this one on October 25th where they chanted in solidarity with Chyah, Tyre, Nabatiyeh and Bint Jbeil. This serves the same purpose as kellon yaani kellon, but the main difference here is that hayoo focuses on other civilians rather than the political class.

It is like saying ‘we are all in this together’ and ‘they can no longer divide us like they used to’.

There have been some chants in solidarity with others MENA countries, particularly in Beirut and Tripoli, linking the struggles in Lebanon to those faced by other people from Algeria to Iraq. Tripoli has had more of these than other parts of the country. In Beirut on October 19th, protesters chanted in solidarity with Sudan, Algeria, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Palestine, Iraq and Tunisia. They also made a point of chanting to all regions of Lebanon, including the Palestinian refugee camps that are so often ignored in the national discourse. On October 20th, protesters sung a Libyan ballad by Adel Al Mshiti that was popularised during the 2011 uprisings. On October 26th, protesters in Tripoli chanted ‘Oh Idlib, we are with you until the death’ as the Syrian city of Idlib continues to face brutal bombardments by Russian and Syrian forces, before repeating the same chant for the Lebanese city of Akkar to Tripoli’s north, thereby linking the two cities.

YALLA ERHAL YA [name] and HUR HUR HURRYEH

In addition to chanting ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam for eight years and counting, neighbouring Syria has provided several chants to the protesters in Lebanon. Two of them are especially noteworthy.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Yalla erhal ya [name], “come on leave oh [name]”, is a popular Syrian revolutionary chant that has been used by Syrians since 2011 to call for the downfall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. You can hear it here in Hama in 2011, with tens of thousands of protesters repeating yalla erhal ya Bashar. Protesters in Lebanon have repurposed it to target the various warlords and oligarchs. As with the original Syrian version, the lyrics change a lot depending on the context. In Lebanon, a dozen different versions have popped up since the beginning of the uprising on October 17th. To name but two examples: In Akkar, protesters chanted yalla erhal Michel Aoun on October 30th, and protesters in Beirut followed suit the next day. The tune has also been adopted with the lyrics changed. On October 29th, protesters in Beirut replaced the main sentence with ‘come on rise oh Beirut’ in front of Telecommunications Minister Mohammad Choucair’s house. That same night, following prime minister Saad Hariri’s resignation, protesters chanted ‘Hariri has fallen’ to the same tune.

As for hur hur hurriyeh, “free- free- freedom”, it remains one of the most popular chants in the region. You can hear it sung in Aleppo and in Hama in 2012 and in Idlib in 2018. Given that Lebanon is ruled by multiple warlords and oligarchs, various chants were needed. On October 19th, protesters used it against Nabih Berri [speaker of parliament], Saad Hariri [prime minister], Gebran Bassil as well as Hassan Nasrallah, Michel Aoun and all of the others. The other main sentence is ghasban aannak, or “despite you”. A common chant would thus translate as “free- free- freedom, we will reach our freedom. Despite you oh [name], we will reach our freedom.”

Given that some of these chants have been adopted from previous contexts, this phenomenon will likely continue, particularly as the structural problems behind the most recent crises are unlikely to be resolved in the near-future. Political chants will continue to be re-imagined on the streets and online, with unpredictable repercussions on the country’s politics.