With fascism on the rise, in years to come we will look back at this political moment as a crucial time in organising history. In the present, that comes with heavy responsibility for stewards of the resistance. Black Lives Matter UK (BLM UK) which, it bears noting, exists independently of its namesake and BLM’s originators in the US, will celebrate its tenth year in 2026. Over the past decade, BLM UK has solidified its positions as one of the many lighthouses in this ideologically dark time, arming anti-racist organisers with political education, resources and community.

I spoke with Kojo Kyerewaa who, on behalf of the national organising team, shared the pressures BLM UK faces, their collectively imagined future for Black liberation and how they are ushering that vision into reality. In this struggle for liberation, that ‘how’ is an essential part of the equation, and many are looking to organisations like BLM UK for the next move.

Contending with class war

BLM UK describes itself as a national, member led, anti-racist organisation fighting to end systemic racism. Though accurate, this pithy description is unable to contain the breadth and depth of the organisation’s challenges, nor its ambitions. Describing the tough landscape that forms the backdrop of their work, Kojo mentions some of the things ailing Black communities in the UK: “fascism and colonialism are rising; our communities are under financial stress, facing increasing surveillance, state violence, and less respite.” Kojo went on to tell me that over 50% of Black children in the UK are currently living in poverty. He spoke about the ongoing struggles of the Windrush generation, and the exploitation of African migrants working in the care industry. The list, of course, goes on.

This cross-section of interwoven hardship is not circumstantial, it’s exactly by design. In fact, the system is working perfectly for those who have weaponised their wealth to shape it – that much is evident in the statistics. While the working class have teetered on the tightrope line between scraping by and destitution, the rich in Britain have been getting richer. Quoting Oxfam’s Takers Not Makers report on unjust poverty and unearned wealth, Kojo explains that, in 2024, UK billionaires’ wealth surged at triple the speed of the year before, bringing its total to £182bn. As he put simply: “what is happening is a class war, and we’re losing.”

Holding on to hope

It’s a bleak but accurate description of where we find ourselves. I asked Kojo what gives him hope. After a pause, he reflects on both the present and the past. He gets animated speaking about the “radical defiance” and “boldness” of young people, and the determination of migrants who – despite the onslaught of the state and the multitude of barriers placed in their way – still manage to overcome, and make it here.

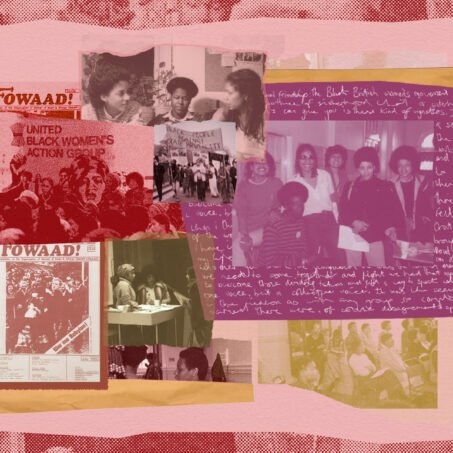

Looking back on the past, he says another source of hope is the giants on whose shoulders we stand. Often, when activists use this phrase they’re honouring our ancestors – as we should! Though, it strikes me as important that he intentionally started by speaking about the elders of the movement who are still with us. Kojo explains that the steadfastness of elders like Zainab Abbas give him hope. As former International Secretary for the Black Liberation Front, a member of the Brixton Black Women’s Group and a contemporary of Olive Morris, she could have understandably become disheartened by the constancy of struggle. Quite the opposite: Kojo recounts that she attended BLM UK’s Festivals of Collective Liberation both last year and this year. “The fact that there are elders who have been fighting longer than I’ve been alive gives me hope,” he says.

Hope and vision for Black liberated futures is what continues to fuel BLM UK. In opposition to this barrage of calculated injustice, the team have developed an even heftier counterweight of revolutionary response.

Turning the tide of class war

On 19th July 2025, BLM UK hosted its second annual Festival of Collective Liberation. Kojo explained that this year’s festival, entitled “Building Black Power” had three themes. The first was facilitating communities to “build mutual aid against poverty”, fostering abolitionist organising against austerity. In the wake of the 2024 race riots and the fascist attacks on migrants, another theme was “strengthening collective resistance to street and state far-right violence”. The third was to “celebrate our thriving Black cultures and engage with cultural production in a critical way”.

As Kojo lamented the commodification of Black culture, and the way it is often siphoned and packaged up devoid of connection to our communities, he was determined that reclamation was possible. “The culture sustains us!” He continued, “it’s our spirituality, our lyricism, our music, our dance which passes on knowledge from generation to generation,” These themes came to life through workshops, panels, film screenings, artistic performances, and in the conversations that happened in between. They created space for people to listen, to share, and to learn.

Crucially, BLM UK has long been turning education into action. On 2nd May 2024, in partnership with a number of anti-raids organisations, BLM UK mobilised people on the streets of Peckham to successfully halt the then-Tory government’s attempt to relocate migrants from a hotel to “a rancid and very unsafe barge” – the Bibby Stockholm.

Kojo also shared the work BLM UK is doing to intervene with the ongoing Windrush scandal. Alongside the Windrush Justice Community Coalition, the organisation is supporting those impacted and making claims to get funded legal aid.

Citing research from JUSTICE, the University of Sussex and Dechert LLP, Kojo illustrated the need for this aid by sharing the story of ‘Sandra’ whose preliminary award was £300, shooting up to £170,000 on Tier 2 review of the case once she had funded legal aid. Putting this in context, he explained, “unlike the four different post office compensation schemes, and unlike the infected blood scandal compensation scheme, the Windrush compensation scheme is the only [one] where the claimants do not get funded legal support.”

Then, he retorted, “we just need to look at each other, we know why.” Through this work connecting those harmed by the Windrush scandal to resourced legal support, BLM UK is making sure our elders get some relief from the financial strain that this state-manufactured scandal brought upon them.

Though, BLM UK refuses to exceptionalise this scandal. With a disapproving look on his face, Kojo spoke about the likes of David Lammy, who will “stand up for the Windrush generation and say this shouldn’t have happened to them because they were British”. Setting apart BLM UK’s position, Kojo affirms “this should not happen to anyone. This violence is never legitimate. Because you don’t have particular paperwork, the state has the capacity to deny you healthcare, to throw you in prison, to remove you from your loved ones? We say no.”

Giving a preview of action they hope to get going with, Kojo mentions the team’s aspiration to make community service provision a part of their strategic approach. He lists two current examples – Global Majority Cop Watch’s breakfast club in Peckham, and the Rastafarian community providing lunches, fresh fruit and veg in Catford – as inspiration. But I’m unsurprised when he also honours the seeds that the Black Panther Party planted when they did the same.

He reminds us, “they didn’t just do breakfast clubs. They did rat catching services, housing maintenance, provided suits or shoes for interviews, helped with travel so people could visit loved ones in prison.” He admits, “I can’t say we’re quite there yet but, in terms of the battle for ideas, it’s not about how you articulate yourself, it’s about showing up for the people.” After 15 years of austerity where many have felt abandoned, this strikes me as a powerful next step for the Black liberation movement. Between their direct action, their advocacy and community resourcing, Kojo was painting a picture of resistance that forms a multi-pronged front in this class war.

Where do we go next? It’s up to all of us

Many of us look to BLM UK for news about what’s happening to our people, how we are resisting, how we get involved. It’s a lot of concentrated pressure. Preparing for the interview, I wondered: should all of us (me included!) be doing more to help situate BLM UK within a broader ecosystem of Black resistance in the UK?

For those looking to engage more directly with the organisation, Kojo says BLM UK is actively looking for people committed to the same values – who want to transform education, end the hostile environment, organise for abolition, build global solidarity, and radically pursue Black liberation.

In practice, that engagement entry point is manifest in Project Timbuktu: an eight-week political education course made up of community-led circles where participants discuss topics ranging from why it is so expensive to be Black and poor, to what reparations, and even exploring freedom dreams where you can reimagine safer, liberated futures by and for Black folks. Though, Kojo adds, “we definitely talk about ideas but the key aspect of Timbuktu is: how do we build community together? How do we learn from each other? How do we realise that our liberation lies in each other?”

With 160 spots open across 5 cities, this programme feels like one of BLM UK’s most open and accessible call to action to date. Its first cohort, concluded just last month and had more than 50 attendees across London, Birmingham and Manchester but this second iteration sees an expansion to Leeds and Bristol. BLM UK is reaching into communities in the hopes that we will clasp their hands in return.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

As an especially visible and vocal part of the anti-racist movement’s lifeblood here, BLM UK faces a complex mix of pressure, responsibility and opportunity. Kojo seems grateful for the recognition of what the team are carrying but, more than anything, humbled by it. “It’s a heavy responsibility,” he admits, “but it’s a privilege to serve the community.”

Collectively building presence

Speaking further about Project Timbuktu, Kojo elaborates: “Ruthie Wilson Gilmore tells us that abolition is not absence, it’s presence. That is what we are trying to develop: presence in community. The white supremacy we have suffered under is not our story, and it’s not our future. We are building a presence to say: we are all that we’ve got and we are enough. We can organise. We can support each other. We can change the world into one that honours our lives.”

As he says this, it threads a loop in my brain between his service, that of the whole BLM UK team, and what they’re asking of the community through participation in this project. They are inviting us to stand alongside them and model the future by believing that all of this is possible.

With an engaged movement, this could become an even more powerful vehicle for growing and sustaining Black organising across the UK. Not yet a decade old, the organisation is still at a nascent stage of that journey. It’s up to all of us to pour into BLM UK’s work – to contribute what we can, to both learn and teach, to take action, and to mobilise our communities – if we want to see that potential fulfilled. We must remember: the Black Lives Matter movement belongs to each Black person who dares to dream of a liberated future.

What can you do?