The first time I met educator, Black historian and feminist activist Stella Dadzie was in 2022, at a workshop she was facilitating at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Along with a group of young Black women, I had been invited to explore her Freedom Fighters digital trail, and discuss the museum’s Transatlantic Slave Trade gallery, giving feedback on how its language and design could be remodelled to educate a new audience.

Over the course of the workshop, conversations about the representation of Black women throughout history began to reflect onto us, blossoming into anecdotes as we exchanged our experiences. There was a softness in the room on that day; the feeling of ease that comes with sharing a space with faces that look like yours.

Brixton’s cultural legacy

Stella and I now meet at the café in the Ritzy cinema in Brixton. Brixton holds a special place in my heart: after moving from rural Essex to South London in 2018, I was desperate to see myself in the faces of those around me. Brixton was one of the first places I truly felt seen and not just looked at, so it was fitting that this was where Stella and I had decided to meet.

To me, Brixton also represents resistance. Despite its rapid gentrification, pockets of the area still cling to its cultural legacy – a hub for the vibrant and diverse Black community and its rich history.

The migration of people invited from the West Indies to England after WWII saw many settle in South London and create lives for themselves in Brixton. The area is also significant in the British Black Power Movement: being the main base for the British Black Panthers and home to many influential Black figures like the Black liberation and feminist trailblazers Gerlin Bean and Olive Morris. Additionally, Brixton was a space of power and protest during the 1981, 1985 and 1995 Uprisings – collective resistance that arose as a response to the police-perpetrated murders, racial violence, and over-policing of the area.

It felt appropriate that Stella and I met at the Ritzy too – a cinema that, during the uprisings of the 80s, was transformed into a site of defiance by Black organisers: a frontline of resistance against the state and a home for rebellious community gatherings and artistic expression.

OWAAD and ‘political Blackness’

Stella had been at an event before meeting me, unveiling an English Heritage blue plaque on Railton Road for her friend, the late Black feminist activist and squatters’ rights campaigner, Olive Morris. Railton Road was where Olive lived and squatted, occupying a flat above a disused laundrette with fellow British Black Panther, Liz Obi. The building, which would go on to become one of the longest-running squats in London’s history, later flourished into a centre for political organising, hosting meetings for Black activist organisations.

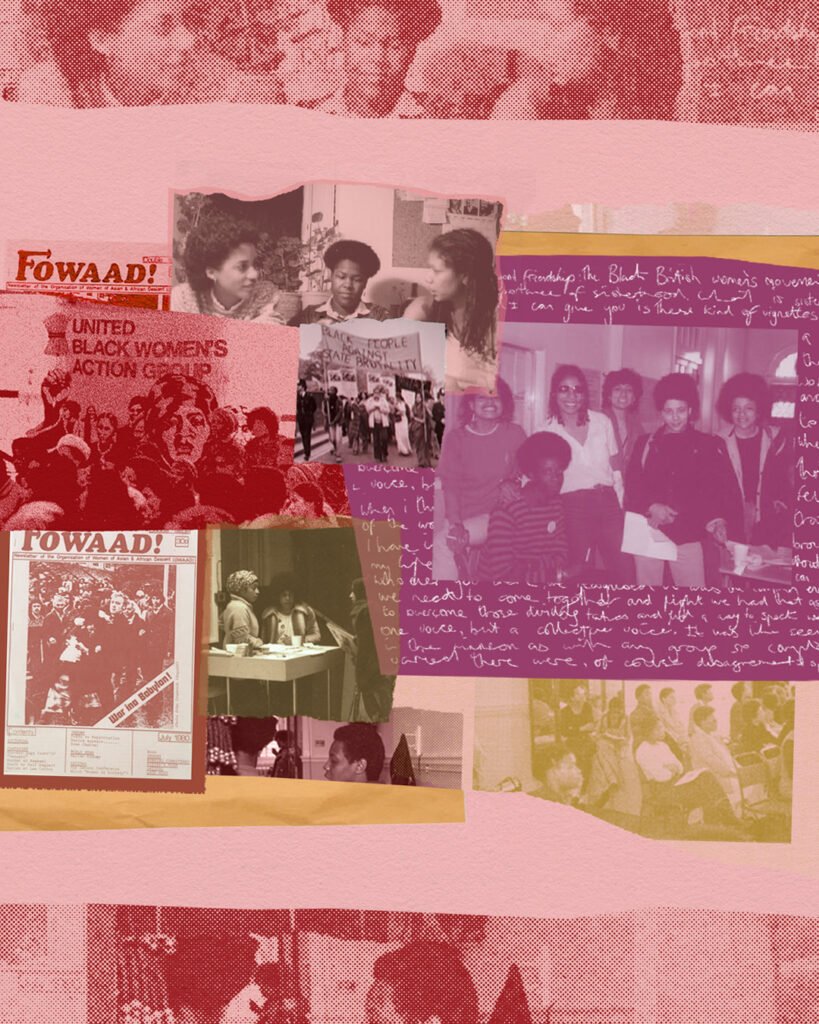

Olive co-founded the Brixton Black Women’s Group, one of the first Black women’s groups in the UK, and later, alongside Stella and other women, co-founded the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD).

OWAAD was a grassroots activist organisation formed in 1978, fighting for the rights of Black and Asian women across the UK. Feeling unheard in traditional feminist groups that privileged white women, and overlooked in Black liberation groups, it was founded to respond to the intersecting issues of sexism, racism and classism, and to highlight the contributions of Black and Asian women to the UK. Though the term intersectionality was not officially coined until 1989 by critical race scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, the group recognised these interlocking systems of oppression and operated under this framework.

Noticing some similarities in the treatment of these women of colour, OWAAD organised around the principle of political Blackness, a term that emerged in the UK in the 1960s. Blackness, in this sense, was not a descriptive category, but instead an umbrella term acknowledging those experiencing structural and institutional racism based on the colour of their skin and their common history of colonial oppression.

OWAAD also acted as a site of refuge and solidarity: to share space with like-minded women and no longer feel isolated in a sea of white faces.

Spotlighting Black women’s stories in Britain for the very first time

During OWAAD’s first conference in 1979, Stella tells me that they had no idea who would turn up. But the turnout reached almost 300, more Black and brown women than any of them had ever seen in one room.

“It was like seeing myself in the mirror,” she says. As with any group so complex and varied, there were, of course, disagreements and specific issues within and between cultures. No group is homogeneous, and other factors like class and colourism contributed to the discrimination they faced. But ultimately, they were united in a common struggle.

“We definitely recognised that racism and sexism had no place for colourism,” Stella tells me. “Whoever you were, we recognised it was the common enemy that we needed to come together and fight. We had that aspiration to overcome those dividing tactics and find a way to speak with one voice. Not just one voice, but a collective voice.”

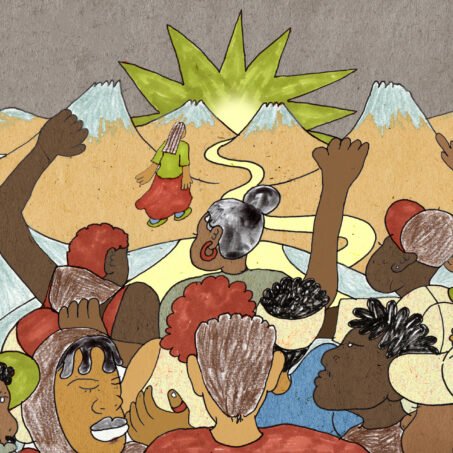

Activism becomes most effective when harnessed through collective power. Recognising that as victims of colonisation, and other interlinking structures of oppression, we must unite as a shared entity – one that confronts, challenges and resists.

Stella went on to co-author the seminal Black feminist text, The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain. Published in 1985, this book was formed from discussions held by OWAAD, exploring the migration of African-Caribbean women to Britain, and their personal, political and everyday struggles.

It was unprecedented – up until that point, Black women’s stories in print were written from an American perspective, or not written at all. It was the first British account created by Black women, and quickly became a revolutionary text for the women’s movement.

This was a time, Stella tells me, that Black women “were pretty much unheard, unvoiced, unseen” – and so The Heart of the Race was instrumental in introducing lived experience and women’s stories as a valid source of knowledge. Its legacy is still resounding today.

Reclaiming our history

As we begin talking about the significance of this book, Stella recalls one of the first launch events OWAAD held. “This young sister stood up and said, I’ve heard these stories around my grandmother’s kitchen table for years, but I’ve never seen them in print. She was very emotional about it. It was about saying: now we have a voice, now we will be heard.”

This representation is integral to the wellbeing and empowerment of Black and other marginalised peoples: to see ourselves and our struggles and wins in books and across different forms of media.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

The privileging of lived experience is crucial to ensuring accurate representation. We know that the retelling of history, traditionally, has come from the perspective of colonisers. Told through a warped lens, concerned with the maintenance of power and the upholding of colonial values, narratives bear burning holes of absence.

Historically, stories about Black women are not truly about us. They rarely include us, or our voices, and if they do, we are seldom the main focus. They detail the events we have been swept up in or the violence we have suffered, written from a perspective that looks around us but never directly at us.

“As a historian, I’ll say this: history can be constructed to tell any story you wish depending on who has access to the tools to do that,” Stella expresses. “History tells the dates and the times and the acknowledged context, but to actually get beneath the skin of the experience, you need people’s lives.” Lived experience as knowledge becomes a form of reclamation, of rewriting stereotypes and false narratives. True stories cannot be reached without the real flesh.

Books and literature, in this respect, can become forms of resistance, enabling radical imaginings and liberated futures. Not only do they act as communication tools to educate and inform, sharing theory and experience on revolutionary matters, they also become a way to express solidarity; to let those suffering know they are not alone in a struggle.

As well as The Heart of the Race, women in OWAAD produced newsletters promoting Black feminist groups and campaigns, and literature from members about issues oppressing Black and Asian women. Stella tells me that she sees writing as “a window into somebody else’s world, somebody else’s reality. It’s a way of exploring ideas and making sense of the world as far as that’s possible.” Black women’s stories are integral to this world-making; to provide glimmers of our realities and conjure up shiny, radical ways of thinking and being.

The simplicity of Black sisterhood

Our conversation moves on to Black sisterhood. When I ask what this means to her, Stella thinks of her activist sisters whom she stood with at the unveiling of Olive’s plaque: “We recognise each other. We slip into a natural groove whether we’ve seen each other recently or haven’t met for 20 years.” That is the beauty of a sisterhood based in solidarity – something that transcends ordinary friendship.

It’s an understanding and recognition so deeply rooted, one I feel blessed to know profoundly. Of seeing pieces of myself in the women around me, of catching my reflection in the fleck of their iris; the air warming when we laugh, outside issues softening and slipping away at once. Of falling back into the ease of friendship, the absence of judgement, not having to worry about code switching or socially masking because we immediately recognise one another. “There is a sense that you don’t have to explain yourself”, says Stella. That you can just sink into the comfort of an unspoken understanding. There is something so sacred about these relations.

Black women so often exist through the eyes that racialise us, in dimensions of harmful preconceptions. Rooted in colonial stereotypes from the days of enslavement, these views have been repurposed and repackaged, existing to contain and oppress us.

They say that we are to be indomitable, superhuman; that we cannot be too confident or outspoken, that we must be without emotion, grow up and harden fast. In public spaces, this is all we can be seen as. There is a coldness that comes with our existence.

Spaces that cultivate Black sisterhood are therefore crucial in allowing us to express ourselves unapologetically, to let us feel vulnerable within ourselves. Environments without the need to conform or bend. No longer do we have to worry about being misunderstood, about being perceived as too little or too much.

Sisterhood from afar when it mattered most

The purest type of sisterhood is unconditional. It can feel instinctive, written into something larger than us all.

Stella tells me a story: one morning after her mother had passed, she found herself sitting on the floor of her office, surrounded by papers and weeping. When, out of the blue, she received a phone call from a sister she had known from ELBWO (East London Black Women’s Organisation). The woman expressed that she felt the need to ring her, because the previous night, she had dreamt about her sitting on the floor, surrounded by papers and weeping. At the end of the call, she invited Stella to pay her a visit.

“That was one of my most poignant moments of sisterhood,” Stella tells me.“This sister wasn’t even a close, close friend, but she was part of our circle. And she immediately tuned into what I needed at that time, which was someone to listen and to be present, and sit with my grief and just let me be.” She continues: “What is sisterhood? All I can do is give you those kinds of vignettes.”

When I think of the women I have in my life, I think of the ways we repeatedly show up for one another. How, when together, it feels as if something around us, a tenseness, a hardness, sheds. I think of the acts of gentle care, how we nurture one another and silently tend to wounds that we ourselves had not even recognised. I think of the way we fell into one another’s lives, became rooted, and how our love has never faltered.

As our conversation draws to a close, Stella’s words linger: “I have a sense of the ancestors working on us and trying to intervene where possible. There’s a force field in us that has brought this about, and all we can do is honour it, value it, and make sure it is remembered… that to me is real sisterhood.”

What can you do?

Read:

- Pre-order Stella’s new book, A Whole Heap of Mix-Up – a collection of personal, political and creative writings

- Stella’s other books: The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain and A Kick in the Belly: Women, Slavery and Resistance

- Do You Remember Olive Morris, an anthology of personal and archival writings about Olive’s life and activism

- Speak Out!: The Brixton Black Women’s Group, a collection of writings by the Black women’s liberation group

- What is Gentrification?

Visit:

- Stella’s collection at The Black Cultural Archives to learn more about her, OWAAD, and UK Black feminist organising

- Round Table Books, an independent inclusion-led bookstore in Brixton, celebrating global majority and other underrepresented voices

- The Ritzy Cinema for independent films, documentaries and events

Watch:

- Mangrove and the Uprising collection by Steve McQueen for more information on the British Black Power Movement

- Rocks (2019) for a tender depiction of young Black British sisterhood