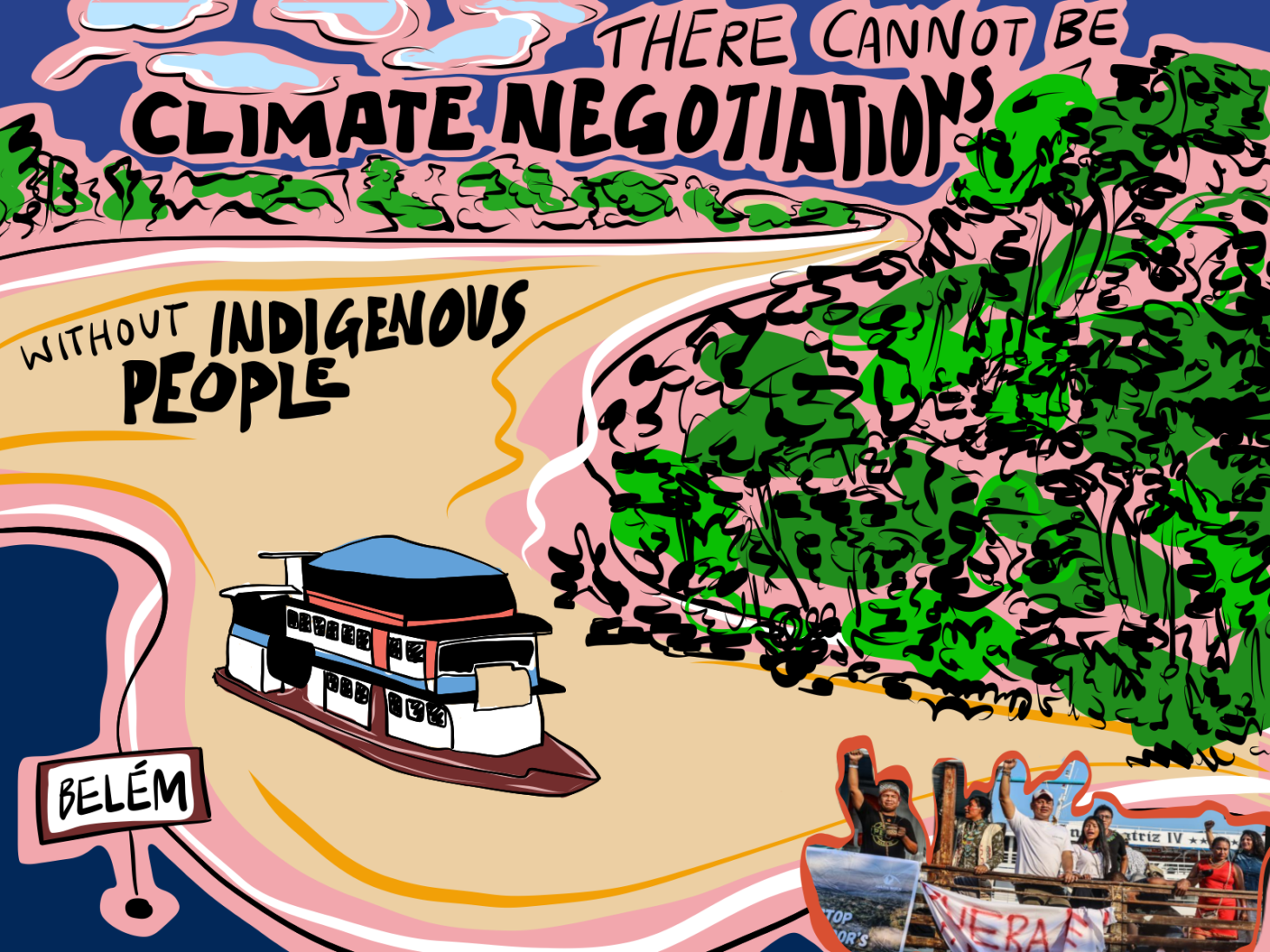

On October 16th 2025, in Coca, Ecuador, 60 Indigenous activists and leaders started their journey of 3000km, navigating towards COP30 in Belém. Their boat, named the Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla, is an initiative to make their collective journey, as well as their presence in the international climate negotiations in Belém known and visible.

This year’s COP30, also named the Amazonia COP, put Brazil and Latin America at the forefront of international climate negotiations and diplomacy, with a special spotlight on the Amazon region. Historically, COPs conferences have been infamous for sidelining Indigenous voices and activism, while evermore promoting the interests of fossil fuel and gas lobbies.

As a French-Peruvian journalist, with family roots in the Amazon region, and working specifically on themes related to environment, climate and international governance, I was particularly interested in the intersection between Indigenous activism and COP30 in the Amazon region.

With the International Court of Justice ruling in 2025 that climate action is an obligation and not an option for states under international law, coinciding with a strong environmental backlash globally, COP30 arrived at a crucial intersection between global setbacks and the renewed urgency of ambitious climate action. In this context, the Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla offered a renewed strategy for visibility, awareness and collective political action of Indigenous actors in global stages.

On 9th November, the Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla arrived in Belém, in time for the beginning of the COP, which will take place from November 10th to 21st. During this COP, the participation of Indigenous leaders and collectives has been central in challenging the status quo, as witnessed during the action of indigenous protesters blocking the main COP30 entrance on 14th November, or the organisation of the “Great People’s March” on 15th November, where thousands of environmental organisations and Indigenous groups organised a protest in the city of Belém to call for action and express their demands.

The Yaku Mama Amazon flotilla

During the journey of the flotilla, I spoke with Lucia Ixchíu, a Mayan Xi’che Indigenous journalist from Guatemala and part of the flotilla coordination team. “We are travelling in a flotilla in an act of revindication, dignity and solidarity between territories,” she explains. The boat has set off from Grandmother Kayambe, a glacial grandmother, where the Napo river, a tributary of the Amazon River, begins. The group left from Coca, travelling upriver, and visiting Indigenous communities on the way.

“Our demands are clear,” Lucia tells me. “There cannot be a climate negotiation without Indigenous people, as a starting point. Indigenous people’s knowledge is central to bring alternatives to the climate crisis and to the destruction of biodiversity.”

The location of COP this year is significant: Belém, a city in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, following COP29, in Baku, Azerbaijan, in 2024. The global conference is also attended by activists and civil society organisations, and hosts a series of events alongside the official negotiations.

This year, one of the most notable events is the People’s Summit, which took place between 12th and 16th November, bringing more than 1200 national and international organisations together. This Summit organised activities and events throughout the city, with representatives present in the official COP30 negotiating spaces. These unofficial spaces allow for organisations to meet and create an alternative space to the Blue Zone (the official venue for negotiations) which not all organisations and activists have access to.

This space creates an organised counterweight to the official space of negotiations, where the demands of civil society, communities and Indigenous groups are more central and visible. On 15th November, a protest, led by the People’s Summit in Belém, was joined by tens of thousands of people to demand climate justice. Members of the Yaku Mama Flotilla have joined the People’s Summit and the protest, sharing their participation on the official page of the flotilla.

10 years after the Paris Agreements were signed, this year is a milestone in international climate negotiations. And for Indigenous activists from the Latin American continent, this is an unprecedented opportunity to make their voice heard in the space of the global conference.

A journey through the Amazon region

“The flotilla articulates solidarity between different territories of Abya Yala,” Lucia explains. “There are people from different parts of the continent, Indigenous leaders from Mexico, Guatemala, Panama, Ecuador, Perú, Colombia, Brazil.”

The Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla has made their action visible globally by being active on social media, sharing their journey with the world with regular updates. Members of the flotilla have stopped in many communities along the way, and organised collective activities, such as movie screenings in collaboration with Muyuna Fest, a jungle based and floating cinema festival.

To understand the participation of Indigenous activists in the COP from a historical perspective, I speak with Jean Foyer. He’s an anthropologist from the National Center of Scientific Research in Paris and a member of the ClimaCOP project, a collaborative research project aiming to document international climate negotiations.

Choosing to sail as a flotilla has a political significance in the history of Indigenous activism, Jean tells me. He explains that the flotilla is inscribed in the history of the recorridos or caravans, which are tours used by Indigenous groups in Latin America to make their demands known in a vast territory. One previous example is the political tour Caravana Zapatista a Europa organised by EZLN (Ejercito Zapatista para la Liberación Nacional), the Indigenous political organisation from the Chiapas region in Mexico.

“This is the COP of the Amazon, the COP of the territories, and we want to amplify the places we reach,” says Lucia. The journey of the flotilla starts by bringing the spotlight first to the diverse territory and communities of the Amazon, at the heart of the defence of Indigenous territories and knowledges.

Making Indigenous voices heard in COP30

The international climate negotiations are infamous for sidelining Indigenous voices, in a context where more than 1500 environmental defenders, between them many Indigenous defenders, have been murdered since COP15 in Paris.

Jean tells me that the first milestone of Indigenous peoples’ participation in climate negotiations is during the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio, otherwise known as the Earth Summit. Here, five major documents were signed: Agenda 21, a set of forest principles, a Biodiversity Convention, the Rio Declaration, and a convention on climate change.

In September 2007, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly of the UN. During COP15, the accords recognised the role of traditional knowledge and innovations by local communities and Indigenous peoples in understanding and tackling the climate crisis.

“Indigenous groups have a particularity to tie the local and the global together, bringing a territorial perspective to global negotiations,” Jean says. “By doing so, they weave these different spaces together, and are able to mobilise different levels of actions, from the international UN arena with Indigenous diplomats, to grassroots activism.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

COP30 is the largest Indigenous summit ever organised, with around 900 Indigenous people registered, and 3000 Indigenous delegates present. “This is both a strong political presence and a symbol,” Jean says. However, the presence of Indigenous activists might not be enough to ensure their voices are considered in the official negotiations.

Back on the flotilla, Lucia questions this history with the present reality of the participation of the activists present on the flotilla. “It is important to guarantee effective participation, with Indigenous people having a voice and a vote in climate negotiations – something that continues to be an enormous challenge for the United Nations,” she says. “Within the framework of COP and these types of spaces, there is a lot of exclusion and violence. We demand direct financing for the territories and communities that are defending biodiversity on the frontlines, and believe that there can be no climate justice without racial justice.”

After the confrontation between Indigenous protesters and security forces of the COP on 14th November, it became clear that spaces of negotiation continue to be spaces of exclusion.

She adds that some of the activists present on the flotilla do not have accreditations yet to enter the official spaces of the COP, preventing direct access to these spaces and adding a challenge to participation. Despite the lack of accreditations for some of the members of the flotilla, they have been part of many meetings and encounters organised alongside the COP – during the People’s Summit, for example – creating new connections and making their journey and presence meaningful in Belém.

After COP30

With COP30, Brazil takes a central role in leading the future of global coordinated climate action, with the world looking at the Amazon and at the hope of multilateralism, democracy and diplomacy, at a time where these are being called into question by the current rise of anti-multilateralism and authoritarian governments in Latin America and around the world.

Jean believes that one of the central challenges of this COP is the effective implementation of what has already been negotiated in previous conferences. Some new mechanisms have already been announced, such as the Tropical Forests Forever Facility, a Brazil-led proposal to compensate countries for preserving tropical forests, with 20% of the funds reserved for Indigenous people.

However, with the progress towards maintaining climate warming under 1.5 degrees still too slow, and the oil, gas and coal industries lobbying to prevent changes, with 1600 fossils fuels lobbyist present at COP30, an increase of 12% since COP29 in Baku, the gap between ambitious negotiations and ambitious climate action needs to be urgently addressed. With Brazil approving on 20th October an oil drilling license for PetroBras on lock FZA-M-59, in the sedimentary basin of the Mouth of the Amazon, the contradictions of economic progress versus prioritising climate action and biodiversity protection remain in Brazil and in the world.

Lucia remains determined. “We will continue to do our work before, during and after the COP. We know that it will be important. Obviously, the challenges are enormous, but we will continue to do our work and raise awareness of the viable alternatives to the climate crisis that Indigenous peoples represent.”

During the meetings taking place on the sidelines of COP30, representatives of several flotillas present in Belém – including Flotilla 4 Change, the Gaza Freedom Flotilla, and the Caravana Mesoamericana por el Clima y la Vida – met with members of the Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla.

As the official negotiations enter their final week, facing the challenge of delivering an ambitious agreement, this gathering of flotillas highlights an important reality: when formal spaces reach their limits, it is often in the unexpected connections and alliances that grassroots activism continues to grow.

These encounters strengthen the collective work of civil society, Indigenous political action, and intersectional networks, helping to build a counterpower which contributes to creating the future and to question with force what happens behind the scenes of international climate diplomacy.

What can you do?

-

-

- Follow the work of the Yaku Mama Amazon Flotilla during COP30 and after

- Read about Indigenous knowledges from the Amazon rainforest with The Spirit of the Rainforest: How indigenous wisdom and scientific curiosity reconnects us to the natural world by Peruvian scientist Rosa Vásquez Espinosa

- Listen to the podcast serie Amazonas Adentro by journalist Joseph Zarate on political conflicts of the Amazon region

- Read shado’s series on Land Defenders

-