“Democracy is on trial across east Africa,” says Sarah Bireete, director of the Center for Constitutional Governance in Kampala. This trial is soon coming to a head in Uganda. In two days a general election will be held, which will decide whether the country will continue to be led by President Yoweri Museveni, who has been in power since 1986, or whether 31 year old Robert Kyagulanyi, more popularly known as Bobi Wine, will emerge as the new victor. However, it isn’t that simple – Wine’s campaign has been characterised by violence, he states he has been arrested everyday for the last 69 days and swathes of people were murdered at one of his rally’s last November. Due to this escalating violence, the below piece has been anonymised for the author’s safety.

Commentators in Uganda have argued that since the promulgation of the 1995 constitution, there has been a crisis in young people’s civic and political engagement.

They assert that youth who are eligible to vote in national elections tend to do so less frequently than older generations and are also less likely to join a political party or trade union.

However, this isn’t exactly the case. In fact, I would argue that young people are more politically and civically engaged than ever before. All around Uganda young people are leading movements, demanding change and taking to the streets to ensure their voices are heard. This is because democracy is being transformed; citizens have found new ways to achieve their civic and political goals beyond the traditional forms of democratic engagement in established political institutions.

The most dominant forms of these expressive or ‘non-institutional’ avenues of democratic engagement include petitions, protests and online activism, especially social media campaigns. This has been made possible by the ease and speed with which young people, who dominate these online spaces, can mobilise for a common cause.

In light of this new phenomenon, new voices are being heard and previously marginalised groups are able to lobby for change in civic, political, cultural or social spheres.

Prominent among these new voices are the ‘ghetto youth’ (young men and women born, raised and living in the slum areas and poor neighbourhoods across towns and cities). These have been catapulted to the frontline of national politics after the triumphant entry into parliament of Bobi Wine, a pop star who comes from Kamwokya, one of the poorest slum areas in Kampala. He was elected in a 2017 by-election to represent Kyadondo East constituency.

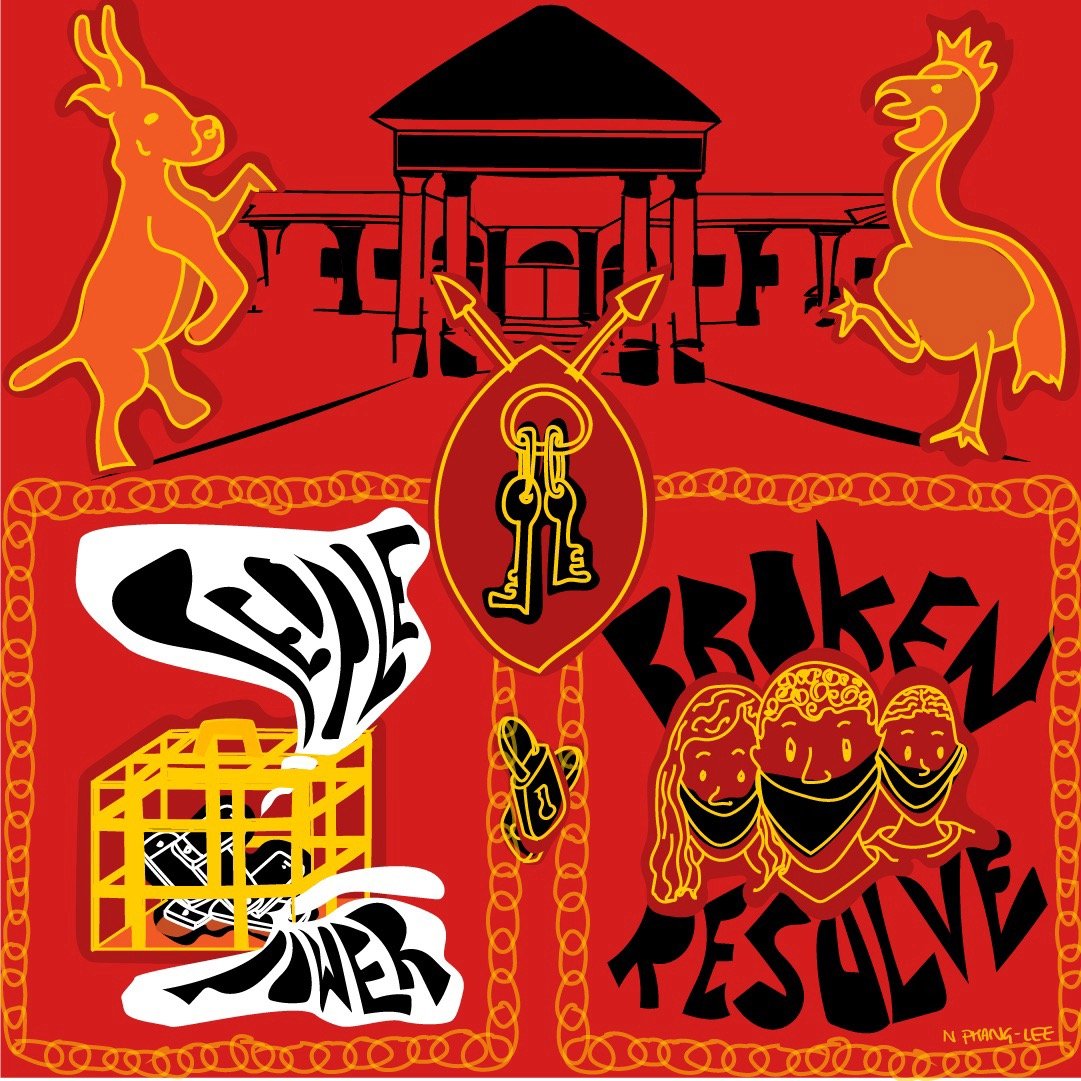

Bobi Wine has inspired a wave of young people seeking political change; the ‘People Power’ movement. In a country where more than two thirds of the population are below the age of 30, the majority of young people living at the periphery of society have long felt neglected by the regime of 76-year-old President Yoweri Museveni. Compared to a man who has been in power for 34 years, the majority of young people seem to easily identify with Bobi and what he stands for.

For the charismatic 38-year-old, who many call the ‘ghetto president’, Bobi Wine has been trending on twitter for the past two years, within seconds garners thousands of likes, retweets and comments on his Facebook posts and has had millions of views on his music videos on YouTube. His fans, supporters and admirers have built a formidable mainstream and social media ‘army’ that broadcasts all his social and political engagements, widely shares his messages and even fundraises for him.

Shortly after his entry into parliament, Bobi Wine’s rise to power was combated by a proposed amendment to Article 102(b) of the constitution. Previously, set in place was a 35 year lower age limit and 75 year upper age limit on the candidate running for president. Removal of these limits would work in the then 73 year old Museveni’s clear advantage to run in the 2021 elections. Furthermore, this would potentially allow Museveni to rule for the rest of his life as he had previously removed presidential term limits in 2005.

Bobi Wine used his influence to organise protests against the amendment he deemed “unfortunate”. He mobilised thousands of young people through his music and online channels. These people then took to the streets and their social media platforms to show their displeasure at what they called an attempt to make Mr. Museveni president for life .

Despite their best efforts, the controversial Article 102(b) was eventually amended and the age limit scrapped from the constitution in December 2017. The spirited fight of these young people, however, had sent a clear message to the powers that be.

Social media had been a crucial mobilising tool for these young Ugandans and therefore political powers naturally sought to restrict it. Shortly after, in July 2018, a daily levy was introduced under the ruse of taming “idle talk” online, when in fact disparaging youth voices were silenced and government revenue was raised along the way. This tax affects more than 60 online platforms including Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter. To access such sites, Ugandans are expected to pay a daily tax of 4Gbx (Ugx. 200).

This is in addition to already established biting data charges. A study by the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) put the cost of acquiring 1 gigabyte of internet in Uganda at £1.98 (Ugx.9,819). Compared with Kenya at £1.79 (Ugx.8,863), Rwanda at £1.62 (Ugx.8,017) and Tanzania at £1.62 (Ugx.8,017), Uganda has the highest tariffs in the East African region. In a country where 1 in 5 people still live in extreme poverty and more than a third of the population live on less than £1.41 (Ugx.6,982) a day, (according to a February 2020 World Bank report), these punishing data tariffs and a daily tax makes internet access reserved only for the privileged. It is no wonder, then, that in the three months following the introduction of the levy, the UCC reported that the number of internet subscriptions to such services fell by more than 2.5 million subscribers. Already, according to 2019 World Bank indicators, less than 30% of the population in Uganda has access to the internet, as a result of limited access to electricity, poor internet infrastructure and high levels of poverty. These deliberate, irrational government policies are only worsening this dire situation.

This electrifying evolution of democratic and civic engagement has concurrently created a fresh battleground: the quest to ensure symmetric internet access to all people, irrespective of class, economic status and social or political views. As activists and citizens looking for answers and solutions to this sad reality, we are often met with insults and graphic comments on our social media posts from government sympathisers and threats from unknown people. We also face censorship from mainstream media channels, meaning we are unable to write opinions, debate policies and criticise these irrational policies. In extreme cases, some activists have been charged in courts of law for the violation of the Computer Misuse Act.

The prolonged ridicule and vilification of these young critics and activists has often broken the resolve and determination of many of our colleagues. And for some of them, because of the promise of material benefits and ‘better’ opportunities, they have gone on to defend these unfair policies and even turn against the cause. They mock and despise those of us who have remained true to the fight for the fundamental right to information.

To be honest, I too hate the ridicule; so much so that sometimes I want to relent. Because I am not merely a noise maker. Nor am I just a wishful thinker. I know that criticising unfair and unjust policies is a big risk that not everyone is willing to or able to take. But also, I know that the bigger risk lies in doing nothing and staying quiet whilst the right to information is being denied.

Without this access to information, my people; poor people, the unemployed youth, and all those on the fringes of society will not be able to make informed and conscious decisions regarding the future of our beloved nation, Uganda. The thought of this terrible predicament is my worst nightmare.

It is necessary to acknowledge that there are host restrictions in place which exist to stifle the diverse and wide availability of information to the population. They exist to curtail the growing movement of political and civic engagement of young people who are the majority users of the internet and its applications.

So, are we, the people of Uganda ready to reconcile with the uncomfortable truth that the internet policies imposed on us are largely unfair? Do we commit to relentlessly engaging and sacrificing our comfort to ensure the data tariffs dramatically go down and the social media tax scrapped? Is the continued unjustified restriction of online content creators and media space a grave concern to us?

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

I hope we have the courage to speak truth to power because for us, the internet is the most potent, if not only available tool to educate, engage, reflect and mobilise.

All this is for the sole purpose of changing the course of our lives through seeking democratic change, structural adjustments, policy reviews and freedoms we have previously only dreamt of but are now firmly within our reach.

We must do this with the firm recognition that struggle is our life.

See more of Natasha’s work on her website and instagram here