Nationally-imposed lockdowns in light of the coronavirus have resulted in a close-to-complete standstill of trade. Economists worry about the knock-on effects in years to come, on global unemployment, markets and currency values. The crisis perhaps proves the unsustainability of national GDP as a measure of success and growth.

But local communities in Nairobi have been keeping trade alive, outside of the bounds of the national market and currency. The non-profit organisation Grassroots Economics has developed a blockchain-backed Community Inclusion Currency (CIC) called Sarafu, a means of exchange that uses simple SMS technology to enable cash transfer, both between consumers and local small businesses, and between consumers themselves. Supported on the ground by volunteers from the Danish and Kenyan Red Cross, Sarafu not only enables consumers to have access to essentials such as food and toiletries, but also sustains the informal enterprises and food businesses that prop up these communities.

Community Inclusion Currencies are particularly vital in times of crisis: when the national currency is diminishing in value due to market crises, the usefulness and value of a CIC increases. The value of national currencies fluctuate constantly, depending on a number of factors: commodity reserves in the country, conflict and political stability, and ‘soft power’, or the brand that the country has on an international stage. In other words, factors that are essentially out of the hands of local communities and citizens often disproportionately impact those at the bottom, and their access to critical goods. CICs such as Sarafu allow communities to define goods and services that are valuable to them, and with the blessing of local authorities, communities maintain their own, internal economic flows without the disturbance of macro factors.

Sarafu is part of a growing number of currency innovations coming from the African continent. “Telecommunication liberalisation” and widespread internet accessibility across Africa has allowed innovators to leapfrog paper-based currency, which is both expensive and time-consuming to produce. Safia Verjee, Innovations Manager at the Kenyan Red Cross, points out that the blockchain-backed digital technology allows for both accountability and transparency of transactions; the Sarafu Dashboard is constantly gathering data about numbers and types of transactions, and is able to identify where the currency is not being used so that it can be redrawn into a community fund and repurposed as appropriate.

Finally, although the gold standard that was used to attribute value to national currencies was largely abandoned by many countries over the course of the twentieth century, the African continent is moving back to gold-backed digital currencies, recognising its own resource / mineral richness. Returning to the gold standard would not only provide community currencies in Africa with legitimate value and weight, but also allow them to retain control of the commodity in a way that has been denied systematically since the days of colonisation and beyond.

Can we take alternative currencies beyond COVID?

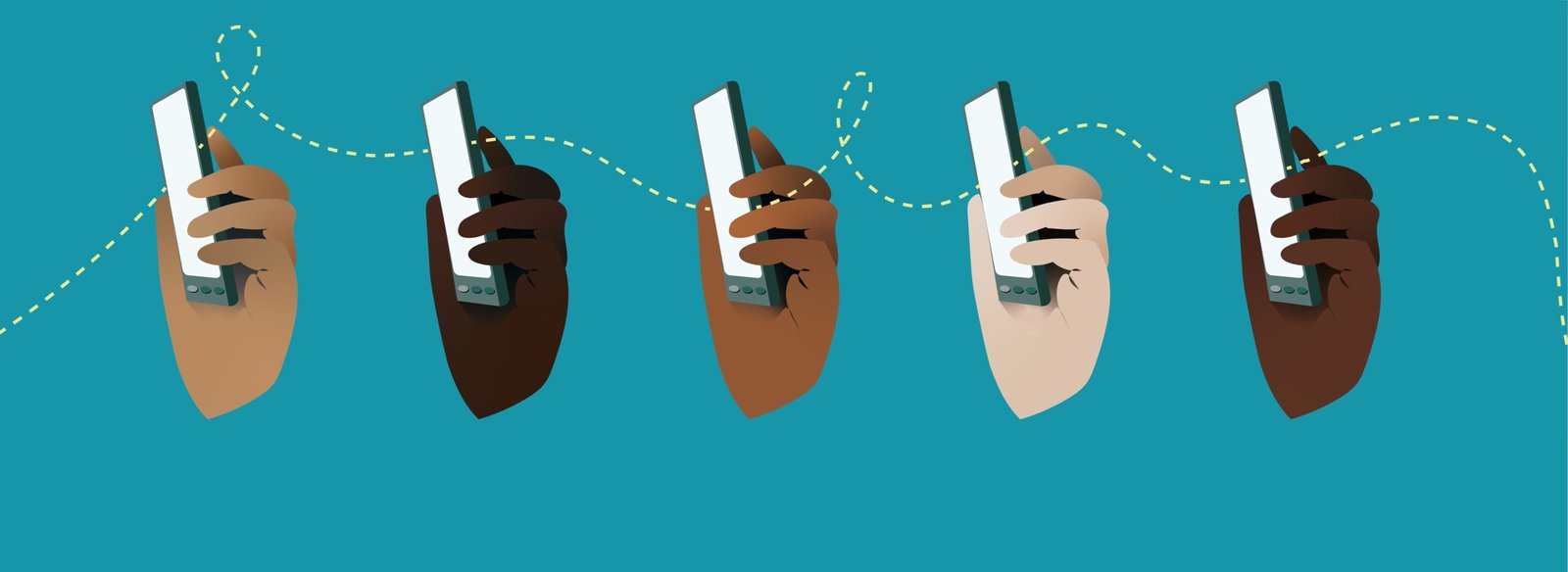

Alternative currencies are not entirely novel ideas; Will Ruddick, founder of Grassroots Economics and Sarafu, has himself founded multiple Community Inclusion Currencies. They, do however, get to the root of what people value. Whilst our current monetary system relies largely on trust and the fact that the vast majority of the global population is embroiled in it, Community Inclusion Currencies centre acts of community as modes of exchange. Mutual aid groups that have popped up during the COVID-19 pandemic represent the sort of society that Ruddick wants to see going forward: “Education, haircuts, waste collection, road maintenance and childcare are all also goods and services to trade,” he says, “and they give people the ability to utilise their skills and capacity.” These exchanges between community members are facilitated through the peer-to-peer money transfer that Sarafu enables using simple SMS technology. Users do not need access to internet technology or smartphones, which in Kenya, can cost three times as much as a feature phone. Only a phone number is needed to be able to transfer Sarafu between community members.

Closer to home, in Bristol, the founders of the local Bristol Pound are pioneering a new payment technology that centres such mutual aid activities through a token reward system. Diana Finch, the Managing Director of the Bristol Pound, is leading the currency through a digital transformation, to become Bristol Pay. They are strategically stepping away from a paper-based currency to an eWallet system that rivals the likes of Google Pay, Apple Pay and PayPal. “The recovery from COVID-19 is the perfect time to trial Bristol Pay,” according to Finch. Alongside a digital currency, she envisions a token system that rewards social, community, and green behaviours, such as cycling around the city or checking in on neighbours. Long-term use of tokens and reward schemes should incentivise sustainable behaviour change amongst Bristol residents.

Alternative currencies often rise up as reactions to crises, as Coco Kanters has found in her time as an Economic Anthropologist. Kanters is currently a PhD Researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands, focusing on the institutionalisation of alternative currencies. Her research interest began in Greece in 2008, where the country was ditching the Euro after the global financial crisis. She saw small currencies pop up as a response to the crisis, which allowed people to trade and keep a sense of local community amongst widespread unemployment and austerity. Kanters’ findings are echoed in a blog post by The World Bank, which states that alternative means of exchange during the pandemic are a method to “get people through an inevitable recession, and not to avoid one.” Crises, therefore, are cyclical, and will keep coming. The key, then, is to move these alternative currencies from reactive measures to proactive forces.

One such inevitable crisis is that of ecological collapse. Several alternative currencies have been stood up to address both environmental sustainability and local economic benefits. In the UK, the Lewes Pound and now-defunct Totnes Pound sought to keep community trade flowing amidst diminishing oil reserves. The Edogawatt in Tokyo allows devotees of a local temple to sell excess solar power to the Tokyo Electric Power Company in exchange for certificates that can be used to redeem ‘favours’ from fellow devotees. Maia Maia was trialed in three schools across Western Australia, and won two UN Environmental Education Awards; it was built on the model of the social cost of carbon, a figure that measures the monetary impact of carbon emissions on present-day economic conditions.

What all three of these currencies have in common is their miniscule scales and radiuses of influence: if alternative currencies are going to be key to proactively decelerating the climate crisis, then the medium of exchange is going to have to become decentralised. National currencies have become a means of asserting state power: “they create monetary desserts, or monoculture economies”, says Coco Kanters, “in a way that leads to a vibrant, diverse economy dying down.” Kanters also highlights how a nationalised currency does not take in-country inequality into consideration. Looking at cities as a basis for economic life not only highlights where trade truly happens, but also prevents money from being redirected to financial hubs. Peer-to-peer transactions keep money circulating amidst a community and personalise exchanges, thus better facilitating the creation of a truly circular economy. Where nationalised money and globalised supply chains have an invisibility to them, Community Inclusion Currencies bring the impacts of production and consumption to your doorstep. As Judith Schwartz writes in Time:

People have a stake in their neighbor’s well-being because that neighbor represents both market and supply chain. Some argue that such transactions are more secure than others because knowing the person you’re dealing with, and his family and friends, serves as a kind of social collateral.

For the African content, Community Inclusion Currencies offer a door to a decolonised economy as well. Historical socioeconomic inequality that has stemmed from imperialism, alongside the factors that determine the inherent value of a currency, have always left African national currencies undervalued. Enough crises have shown us that capitalism is not working for the masses, and will continue to deepen divides in the upcoming climate crisis. After working with economic specialists, Kanters has found that “money is consciously designed to have social rules, determine our behaviour as humans, and our economy.” So changing the rules of money is the first port of call.

Illustrations @raquelboira