In September 1884, the Highland Land League gathered in Dingwall, a small town near Inverness, to lay out their demands for land reform. 140 years on, and the Dingwall community hall was packed out with crofters, land workers, activists and radical historians gathered to discuss issues of land in modern Scotland, and to learn from our 19th century comrades about how to take action for land justice.

A legacy of land resistance

It’s not the history I learnt about in school, but Scotland has a strong tradition of land resistance. In response to an early wave of enclosures in lowland Scotland, the farmers of Dumfries and Galloway staged the ‘Levellers’ Revolt’, which included coordinated dismantling of stone dykes (walls) used to enclose previously common land, as well as rent strikes, rioting and mass protests.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Highlands were subject to a brutal programme of land clearances, with hundreds of thousands of people violently dispossessed and displaced to make way for large-scale sheep farming. This was met with fierce resistance from Highland communities, culminating in The Crofters’ War in the 1880s.

The Highland Land League played a central role in organising this resistance and campaigning for political change. Modelled after the Irish Land League, they mobilised communities across Scotland to demand the redistribution of land to the people who worked on it. Their tactics included boycotts, rent strikes, land raids (what we would now call ‘occupations’), mass protest, physical confrontation, and – my personal favourite – mischievously relocating large numbers of sheep.

In tandem with coordinated direct action, they formed a political party and had members of parliament elected to advocate for their cause. This medley of approaches resulted in a significant victory in 1886, with the introduction of crofting legislation granting secure tenure and fair rents to agricultural workers. Crofting continues to this day, with more than 20,000 crofts present across the Highlands and Islands. It is a unique form of small-scale agriculture, in which tenants incorporating communal grazing rights and traditional sustainable land use practices and continuing a shared cultural community.

In the early 20th century, crofters returning from World War I were denied land which had been promised to them if they went to fight. Highland communities responded with another wave of land raids, particularly in Skye, forcibly occupying and farming the land that should have been theirs. The government eventually stepped in to purchase various estates across the Highlands and Islands and redistribute them to returning servicemen and their families. In more recent years, mass trespass and public pressure resulted in the introduction of the Right to Roam in 2003, granting everyone access to land for recreation.

Researching this history in preparation for the event in Dingwall, it struck me that meaningful changes to land legislation in Scotland have rarely been brought about by asking nicely.

The struggle continues: barriers to land access in modern Scotland

However, despite the remarkable actions of our forbearers, the land system in Scotland today remains pretty dire. We have the most concentrated land ownership in all of Europe, with just 433 people owning more than half the country. The largest private landowner in Scotland is currently the guy who owns ASOS.

Corporate land grabs for natural capital projects and carbon offsetting schemes are pushing up land prices and increasing the concentration of ownership. Crofting is increasingly inaccessible, with crofting tenancies now selling on the open market for hundreds of thousands of pounds. In spite of centuries of resistance, enclosures and clearances were highly successful overall – today only 1.2% of the population works on the land.

Access to land is a major challenge for people who want to work in agriculture, be they new entrants to the sector or folk whose families have been farming or crofting for generations. The price of land makes ownership impossible for all but the wealthy, and market pressures have greatly reduced the number of farming tenancies.

At the Landworkers’ Alliance, a union for land-based workers where I work as a campaigner, we have many skilled and dedicated members who are struggling to obtain land on which to work. I myself dream of having a wee farm when I grow up and producing food for my local community – but I am already well into my thirties and the prospect still seems fanciful.

Reviving a movement for land justice

It was in this context that the Landworkers’ Alliance and the Scottish Crofting Federation organised this gathering for land justice in Dingwall this year, to commemorate the feats of the Highland Land League and revitalise a grassroots movement for land reform in modern Scotland.

The event brought together folk from across several generations and with a great diversity of perspectives and experience to begin planning how we can take action for land justice today. The strategies and tactics which emerged from the discussions were as exciting and varied as those employed by the Land League, including guerrilla growing on unused land, political education and storytelling, coordinated occupation of second homes, and local boycotts of companies involved in private natural capital projects.

The political plotting was punctuated by a delicious meal produced by local farmer and activist Col Gordon, and the day was rounded off with a Gaelic waulking song – traditionally sung by crofters as they worked wool. I was so buoyed up with excitement from the day that I gave an interview to BBC Alba. They didn’t show it in the end, which I’m taking as proof that my words were too revolutionary to be aired.

However, our action wasn’t contained within the one gathering. We have also been involved in running local workshops on land justice across Scotland, including a memorable and lively tour of sites of historical land resistance in Skye, which took place in horizontal rain.

Harnessing grassroots energy

Everywhere we have been, in both rural and urban settings, there has been a huge amount of enthusiasm from local people to tackle land inequality. Describing my experience of campaigning for land reform at the Scottish Government level as disheartening would be a colossal understatement, but running these events has reassured me that the spirit of land resistance is alive and well in communities across Scotland.

The challenge before us is to harness this energy into a coordinated movement advocating for the redistribution of land to the people. While in other parts of the world peasant and farming communities have successfully led revolutions through sheer numbers, centuries of dispossession have left much of our population here with little connection to the land.

To overcome this, we must build our movement around shared material needs of working class communities across the country, such as access to housing and good local food. Those who work on the land must play a central role in this fight, but we need a much broader grassroots movement to effect real change. As the Highland Land League put it: “Is Treasa tuath na tighearna – The people are mightier than a lord.”

What can you do?

- Explore the history of land and resistance in your own area, and be inspired by international peasant-led movements for land justice.

- Holding your own land justice workshops can be a great way to learn from others in your area and begin action planning – reach out if you would like a workshop template to get started!

- If you are based in Scotland, you can get involved with the Landworkers’ Alliance campaign for land reform – follow us to find out what events and demos we have coming up.

- If you are based in England, you can get involved with the Right to Roam campaign, who host regular protests and mass trespasses calling for public access to land.

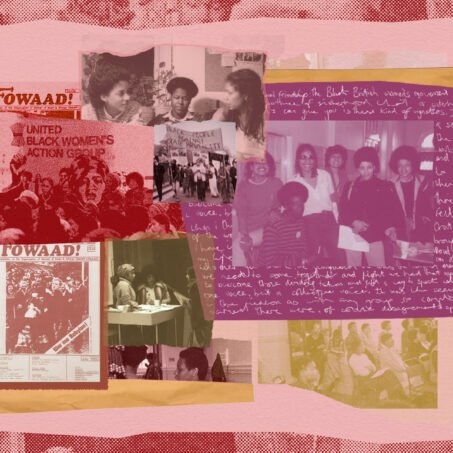

- Check out Land in Our Names, a grassroots BPOC collective who do some incredible work connecting land, racial justice and reparations in the UK. Housing is also a vital aspect of land justice, so consider joining your local tenants’ union.

- Listen to Shado-lite S2 Ep5: Home on the move, the Right to Roam

- Read: The road to common ground, an extract from Nature Is A Human Right