Kerry James Marshall: The Histories is an exhibition featuring the works of internationally acclaimed artist, Kerry James Marshall, curated by Mark Godfrey. It ran at the Royal Academy of Arts in London between 20th September 2025 and 18th January 2026.

Marshall is known for reframing Western art history to centre Black life, identity, and visual presence. We see this in the vivid and large-scale paintings that challenge the traditional absence of Black figures, and instead represents them in various scenes ranging from everyday life to historical contexts, including the civil rights movement. The subjects of the works are often depicted with very dark, almost black skin tones, and are often surrounded with vibrant colours.

As I have done many times, I left it too late to talk about it. I did see the exhibition with a friend at the start of its run, but as you can see, I arrived late to the party when it came to actually discussing it. When I realised it was reaching the end of its run, I decided it was better late than never, so I set out to see it one last time.

The art of loving

When I went to see the exhibition for the first time, Olivia Dean’s The Art of Loving had recently been released, and I was still glowing in the beauty and simplicity of I’ve Seen It. I left the exhibition thinking about that song, singing it in my head, and the journey back home at the end of the day was spent listening to the song on repeat. As I listened, I wondered why I left the exhibition thinking about love…

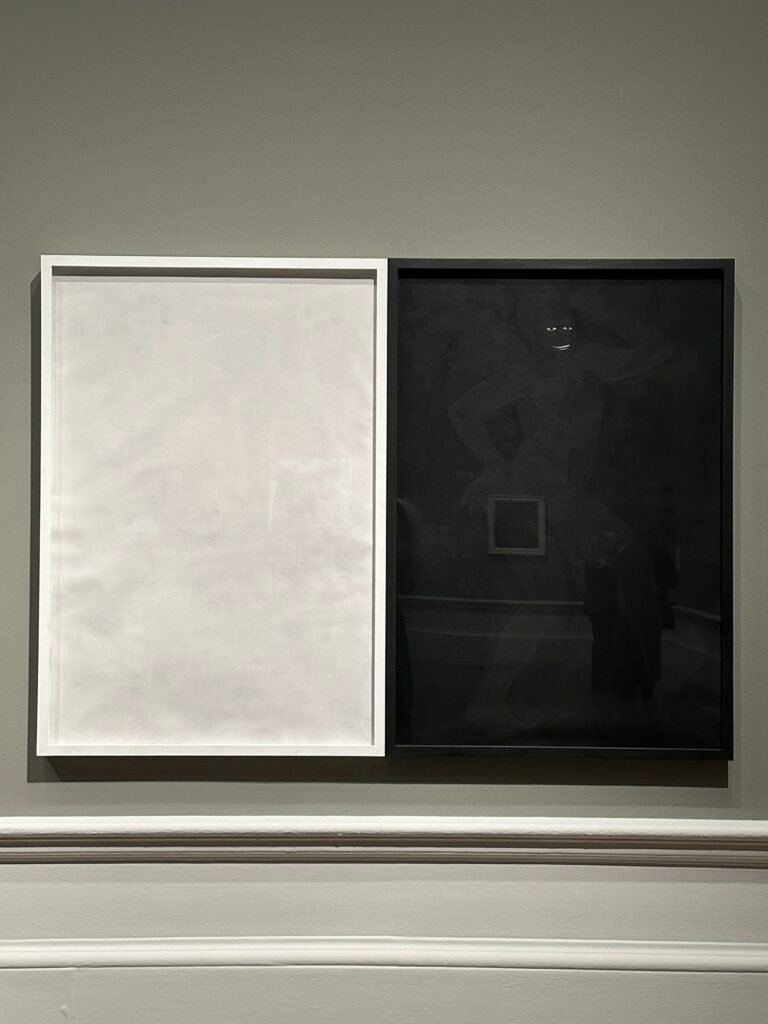

There are around 70 works on display at this exhibition. It’s safe to say it’s extensive. And it is as diverse as it is sprawling. Some of these works explore the condition of Blackness in Western society. The Invisible Man section, specifically, interrogates what it means to be unseen, overlooked, or erased by drawing on Ralph Ellison’s novel, Invisible Man. Many of the works in this room are painted in very dark tones, often black on black. It can be hard to see a subject at the first glance, but the details are often there, either through the textures, the whites of the eyes and teeth, or the deliberate signalling of a figure.

So, in many ways, the exhibition forces us to confront various aspects and tensions of Black lives. Marshall’s work is fundamentally one of resistance and refusal, and I believe one built on artivism (using art as a form of activism) to centre Black subjects in a space where they are underrepresented. While I could see this, I was curious why I was most interested in what it had to show us about romance, and experiencing romance in the midst of these tensions. Why did I simply leave there thinking about love?

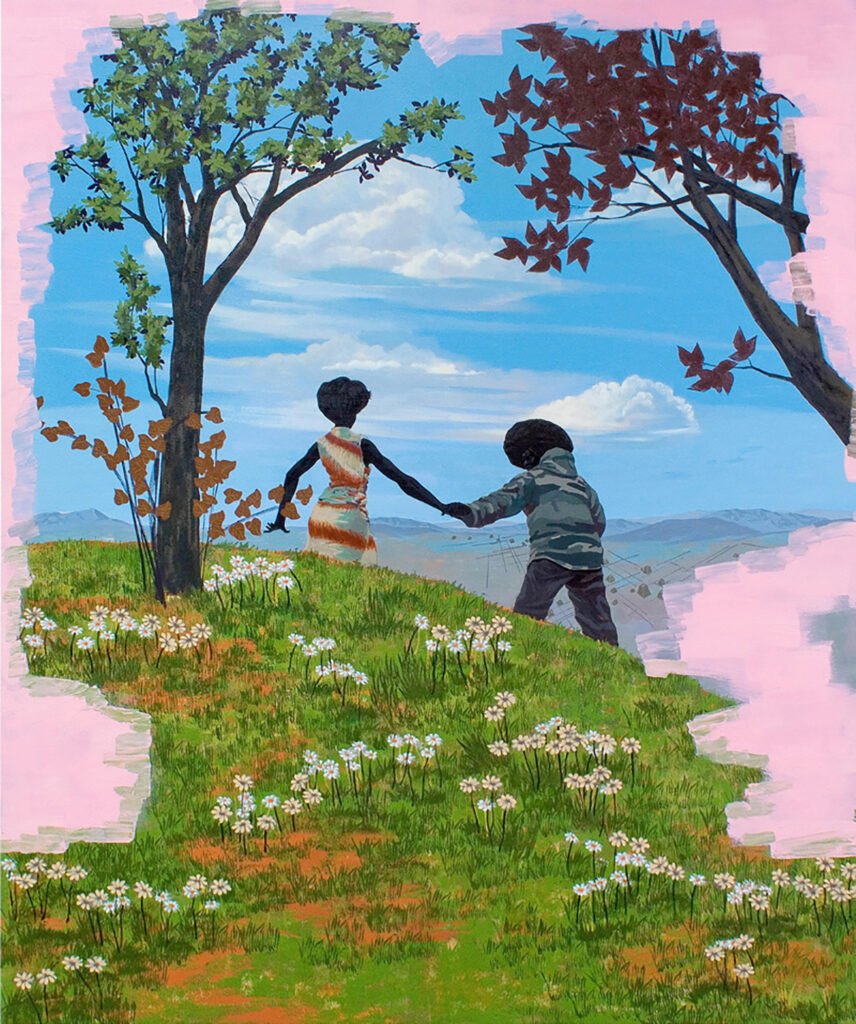

As I thought through this during my second visit, it dawned on me that this is because despite Marshall’s work being about resistance and liberation of Black lives, it also squarely places love within that framing. Various pieces show love in various forms, but especially ones that appear to show romantic love and place Black intimacy at the centre.

One of those pieces that stood out to me was Untitled (Blanket Couple), 2014, which showed two subjects lying on a picnic blanket. It seems to be a quiet and private moment that treats this very ordinary affection as precious.This piece was especially resonant to me because on my second visit, an elderly couple had paused to look at it. They took it in, discussed it, smiled at each other, and the gentleman wheeled the woman off. I hope they are deeply in love, because it was such a simple and beautiful moment to show me that love is, in fact, in the air.

I paused to consider how much tensions are in the world, the constantly shifting yardstick of marginalisation, and how Marshall reflects on these in his works. These thoughts and my experience at the exhibition prompted me to ask: do we have the room for love in the fight for liberation?

Are you currently in love?

Before I explored the room for love in the fight for liberation, my first point of curiosity was to understand which of my activist friends would currently say they were in love. With the state of the world, the cost of activism, and the toll it takes, are they making time for love? I got some interesting responses:

Yes, I am in love… I mean not in the soft, careless way people imagine, but in a deliberate, resistant way. (T)

I am not in love, but I am in love with life and its possibilities (F)

I am currently in love. In love with myself. In love with my friends. In love with every beautiful thing Spirit and my ancestors allow me to experience despite the hellscape all around us (A2)

One thing was for sure: they are in love! They are experiencing love for others and themselves; platonically and romantically; locally and internationally. And I love this for them. They even noted, specifically, that they are happy to be in love despite the ‘shitshow that the world is’, and how ‘on fire the world is right now.’

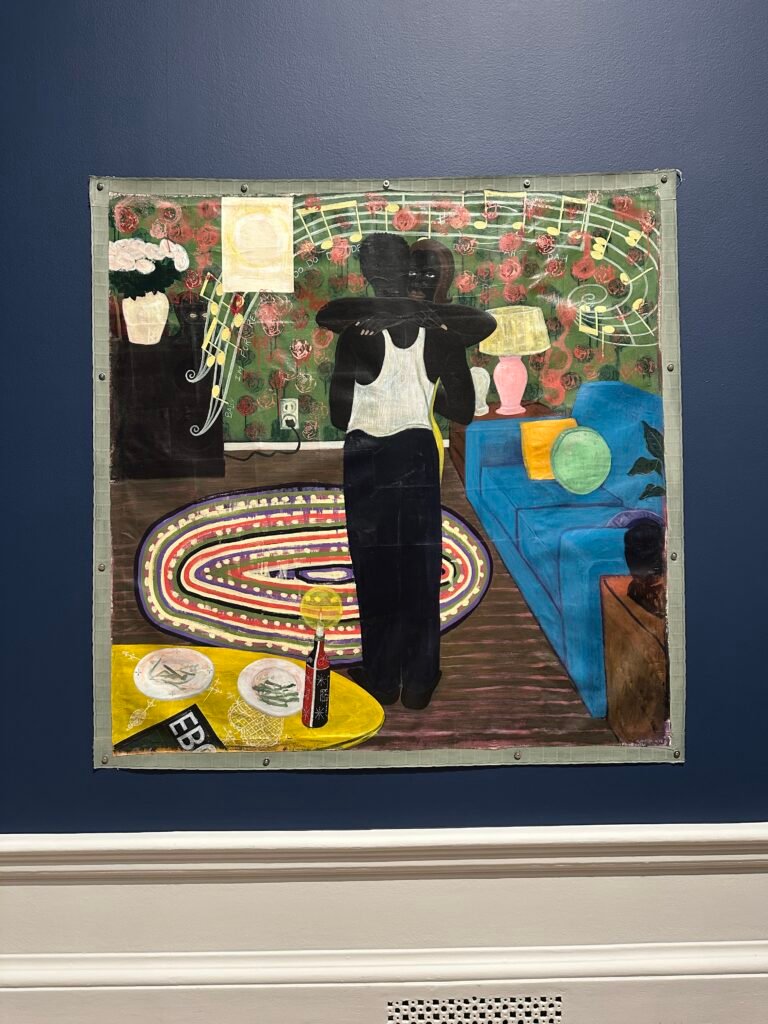

Of course, the subjects in Marshall’s pieces are also currently in love. In Slow Dance, 1992-93, a couple is holding each other in a small room, with music notes floating, with the lyrics to Baby I’m for Real by The Originals.

But perhaps my favourite and the most romantic piece to me is Untitled (Porch Deck), 2014. It perfectly depicts what I describe as the perfect day with a lover. It’s a simple expression of romance, where being in the same space is enough. The closeness of the couple is quiet, they are not embracing, and there are plants. I imagine jazz music playing in the background, and that they are simply enjoying being in each other’s presence. As a true quality time baddie, this was for me. This is why I have the poster hanging on my living room wall as we speak.

Do we have the room for love in the fight for liberation?

And now to get to the question at hand. Anyone who has engaged with any Black feminist thought, including bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Toni Morrison, can tell you the answer to this question is a resounding yes. In fact, they’ll tell you that love is fundamental to the fight for liberation. However, I wanted to see what these activists felt about this, and I would say they agree:

There is not only room for love in the fight for liberation, love is central to it. Liberation that excludes love reproduces the same systems of control it claims to resist. Love is what prevents our movements from becoming purely reactionary or transactional. It grounds resistance in care, accountability, and collective survival. (T)

Fundamentally I think love as a praxis is what guides liberation. I think that part of liberation is the understanding that tearing down systems involves different roles and a lover offers that soft spot to lay your head in order to re-energise, regroup etc. I don’t think it’s supposed to be viewed as a distraction or veering off of liberation’s path. I think it acts as that thing you hold onto for dear life in the midst of it all, because it offers something tangible in the midst of it all. Especially now when the finishing line is constantly being moved. (D)

I think we have room for love in the fight for liberation because I believe the right kind of love will complement what you’re doing and will even be part of the winds moving your sails and giving strength and light in whatever fight one is in. Many of us have the capacity to contain multitudes and complexities when they are aligned. (F)

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

I have room for [love] in this fight. It is what keeps me grounded… I think my partner is in many ways a reflection of all the things I love about doing community work. (A1)

Love is absolutely necessary in this fight for liberation. Without it, we have destruction and subtraction, hopelessness and despair. Liberation requires us to remain hopeful and connected to something bigger than ourselves. Love is what connects us. Love is what keeps us going. In its most expansive and active form, it is the scaffolding for any sustainable movement. It is what allows us to imagine, build infrastructure, care for ourselves and others into the tender futures we wish to create (A2)

I think love is what is most needed in the fight for liberation (H)

So clearly, yes, we have the room for love in the fight for liberation. Those fighting for the liberation have said so, and they ground their reasoning in praxis.

It would seem Marshall and Godfrey, the curator, agree, because it is overtly stated in various sections of the exhibition, but most especially in the VIGNETTES room, which says:

By painting romantic scenes, Marshall produces images of resistance… Although the paintings are filled with flowers and lovebirds, the various scenes are marked in other ways by signs of protest, including burning tyres and political flags. Surrounded by pink brushstrokes and presented as dream scenes, the works also raise the question of whether Black couples can really relax in public spaces or if this idea remains an illusion.

It is precisely to explore this illusion that I felt the need to ask activists if they are experiencing love and how that fits in the fight for liberation. The relaxation in public spaces might not be there, but the love is. Another friend says: “in Nigeria, [being in love] alone is political because to love as a queer person here is to exist in direct opposition to state violence, religious moralism, and laws designed to criminalise intimacy and erase our humanity.” It is not relaxing, and it is definitely not public, but it exists.

Many of the moments of intimacy and romance between the subjects in Marshall’s exhibition are in private spaces. Even when they are in public spaces, they exist in private moments, outside of the gaze of the public. They show how the absence of love, romance and intimacy from public view is not their absence from our lives altogether. They show that visibility and publicity are not the same as tangibility and legitimacy.

While I cannot make out any overtly queer subjects in Marshall’s work, I hope these thoughts can resonate with queer people that exist in spaces where their love has to be confined to the private sphere. Perhaps the love we can access right now can only take shape in private, and that should not make it any less real or tangible.

The room for love in the fight for liberation

The room for love in the fight for liberation is made complex by the state of the world. In fact, one of the people I spoke to for this article says:

I think it looks different now though than what those who came before us had. Like late capitalism has this way of disjointing individual and community needs. It’s something I’m still processing but I’m looking at it from the perspective that capitalism promotes individual success/self sufficiency because there is more to extract from an individual than from a group. The reason why you can’t share a Netflix account in this era. (D)

The part about not being able to share a Netflix account really hit home, because I remember a time where that was how you upgraded the talking stage.

But nonetheless, it would seem love is no longer simply about emotional connection (and bell hooks would argue it never really was) or mutual support, and is instead being experienced under conditions that fragment community and encourage people to operate as isolated units. This is fundamentally antithetical to the fight for liberation.

I cannot emphasise how exhausting it is to see a friend become MIA once they get into a romantic relationship. Love is experienced in silos, and in the nuclear, monogamous sphere that constantly pushes us away from collective and mutual care.

So, it would seem that if we are to have the room for love – which we do – it’s a specific form of love: one that sits within community and collective care. And it would seem this is exactly how the people I spoke to have come to experience it.

When describing their partner, one of the people I spoke to says:

They are hopeful, loving, thoughtful, and supportive of me and random people we are in community with and that reminds me that that’s what we need to overcome, especially when things get dark. All the reasons I do community work are amplified when I’m with them (and everyone else I love, to be very honest, but theirs is the strongest example). (A1)

With that being said, I hope I have been able to convince you and not confuse you that not only do we have the room for love in the fight for liberation, it is fundamental to it.

What can you do?

Watch some (non-exhaustive) rom(coms?) to lift your spirits:

- The Best Man, 1999

- Beyonce (The President’s Daughter), 2006

- Boxing Day, 2021

- Brown Sugar, 2002

- Deliver us from Eva, 2003

- If Beale Street Could Talk, 2018

- The Royal Hibiscus Hotel, 2017

- Rye Lane, 2023

- Two Can Play that Game, 2001

- The Wedding Party, 2016

- The Wood, 1999