The sharp rise of the Black Lives Matter movement earlier this year has made anti-Black racism an increasingly highlighted issue. The death of George Floyd, an American man strangled to death under a white police officer’s knee has become a global symbol of Black oppression. George Floyd’s death is not an isolated case by any means, but often our discussions around Black oppression revolve around cisgender male’s experiences, and Black woman’s oppression and threats to their livelihood becomes secondary, if discussed at all.

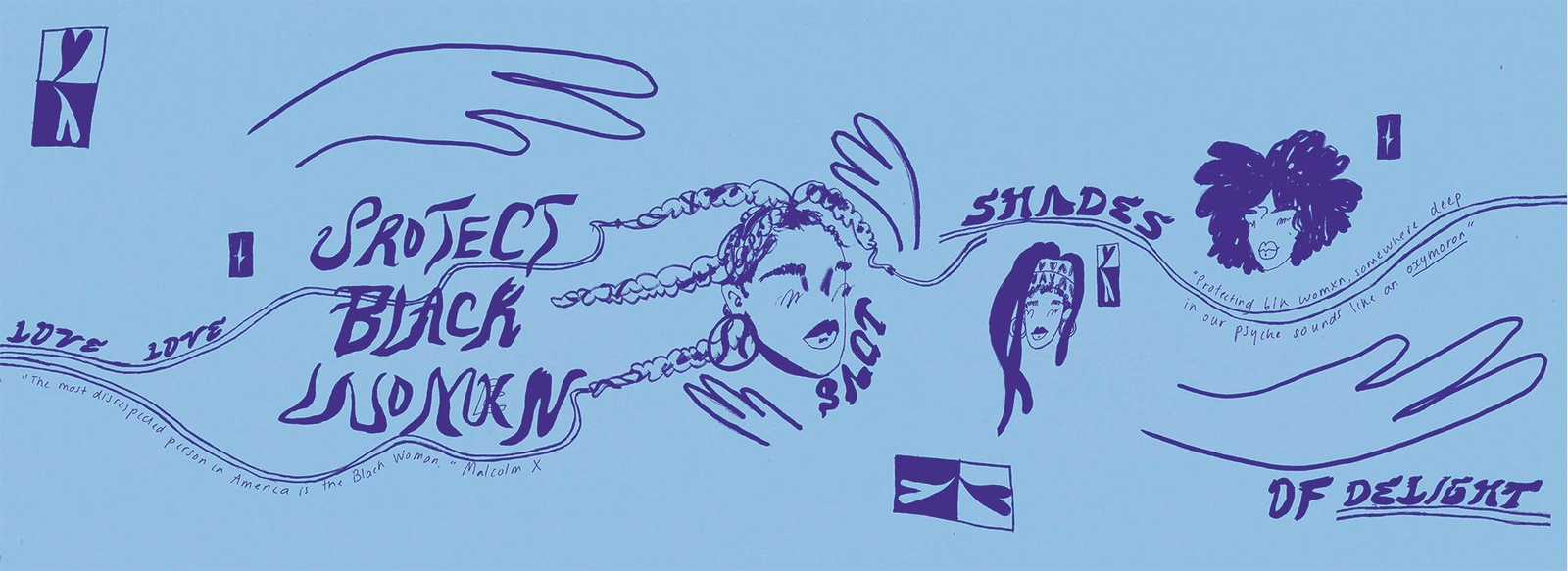

Megan Thee Stallion has bravely used her platform to address these double standards, calling for us to “Protect Black Women” at a recent SNL performance and penning an emotional essay for The New York Times. Megan has first hand experience of what it’s like to be unprotected; following a shooting with male musician Tory Lanez her claims that she had been shot whilst walking away from him were met with scepticism and disbelief. She had to share explicit images of her ankle with bullet holes in it on Instagram to quell people’s doubts – an often familiar narrative when it comes to Black physical pain; it must be visually seen to be real.

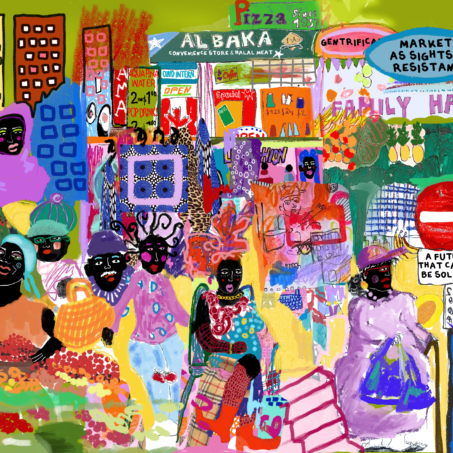

We live in a culture of disbelieving Black women, minimising or ignoring their pain and hurt. Malcolm X said clearly and unequivocally “the most disrespected person in America is the Black woman”, a statement that clearly still rings true today. It’s now been confirmed that Black women played an integral role in defeating Trump in the US elections. Stacy Abrams in particular has been noted for her grassroots efforts to get Black people to vote Democrat in Georgia. But even in this new Black Lives Matter era and being on the cusp of a new political administration, is America as a whole showing up for Black women?

‘Protecting Black women’, somewhere deep in our psyche, sounds like an oxymoron. Black women are rarely painted as vulnerable or in danger. Every Black woman has been told explicitly at some point that she’s “strong”, the literal antithesis of how we view femininity typically. Black females are “powerful” and “independent”, statements that sound positive but can be insidious microaggressions. The flipside of this narrative is that it becomes difficult to imagine Black women as ever needing help, feeling pain or having emotions. The ability to see Black women as humans who can be vulnerable becomes severely limited. This is the complete opposite of how white women are portrayed – as soft, fragile and ‘damsels in distress’. Disturbingly, even the Black Panther leader Elridge Cleaver professed that “there’s [a] softness about a white woman” but a Black woman “seems to be full of steel, granite hard”. Fast forward to 2020 and serious contender for Karen of the year Lana Del Rey awkwardly compared herself, painted as a fragile, vulnerable white woman who sings sad songs, to a host of mostly Black women who she hypersexualised and alluded to as, you guessed it: “strong”. Consequently, this embedded belief in Black women’s perceived lack of fragility makes it completely unnecessary to care about or protect Black women.

Being viewed as strong also means Black women are hyper-masculinanised; like Black men, they are also viewed as a physical threat, prone to violence and anger. Women caricatured as mouthy, angry and difficult rarely garner sympathy and are easily dehumanised – the British press played on similar stereotypes with the Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle to devastating effect. This was of course in contrast to the fragile, delicate English rose Kate Middleton who behaves as a “good woman” should and keeps quiet. This attitude leads to Black women also facing some of the harshest consequences of police brutality. The horrific death of Breonna Taylor, shot to death nine times by police in her bed with no reasonable justification, has not received the same level of attention as other recent instances of police brutality against Black men. Black women’s plight against racialised violence becomes simply invisible in conversations around racism.

The African American Policy Forum released the report #SAYHERNAME to increase awareness of police brutality against Black women, highlighting cases where Black women have been killed by police in front of their children. India Kager, a post office worker and Navy veteran, was killed by the police with her four-month-old child in the back seat. The concept of Black womanhood has to extend to the trans community as well; Black trans women are extremely vulnerable to physical abuse in general and have a life expectancy in America of just 35. Even in the context of Black Lives Matter, Black trans women are at greater risk: Aja Raquell Rhone-Spears was stabbed to death at a peaceful vigil for Tyrell Penney, another homicide victim, in Portland. Her name was added to the growing list of Black trans women murdered in the US. The irony cannot be lost that Aja’s murder happened in the state where people are still on the streets protesting about George Floyd. Our approach to conversations around anti-Black racism has to be intersectional, and not just centre around Black cisgender men’s experiences.

The phrase “protect Black women” remains controversial – but ultimately it’s because we don’t really view Black women as human. The basics of how Black women are viewed through a racist lens continue to be largely ignored or misunderstood by many people. When we reduce people to a one-dimensional caricature we cease to view them as people like us, who are multidimensional and deserving of the same rights others enjoy.

Many white American liberals are no doubt relieved that Black women have shown up in this election and voted for Joe Biden; certainly, they have been more reliable than white women, 55% of whom were happy to vote for a nakedly racist, misogynistic candidate. But to what extent has America really shown up for Black women? The receipts are there, and America owes a hefty debt to Black women that is long overdue. So let’s hope this new movement for anti-racism, and what could be a new political dawn can extend to all Black women too. Until then, the phrase “protect Black women” needs to keep being said.

See more of Luci’s work on her instagram HERE