In the WWII chapters of British history textbooks, the Kindertransport — the organised rescue of nearly 10,000 predominantly Jewish children from Nazi-occupied territory to Britain — tends to hold a certain pride of place. It’s a safe, celebratory story of philanthropy done right, a tale of British derring-do on the eve of war. Its status is immortalised in Frank Meisler’s 2006 bronze sculpture of five refugee children in Liverpool Street Station; its lessons of trials and redemption narrated by Judi Dench in the Oscar-winning feature documentary Into the Arms of Strangers (2000); since 2001 its key heroes have been celebrated as part of Holocaust Memorial Day. Its characters, archivist Caroline Sharples writes, ‘have proven themselves to be respectable, educated, and hardworking individuals and valuable members of the community.’

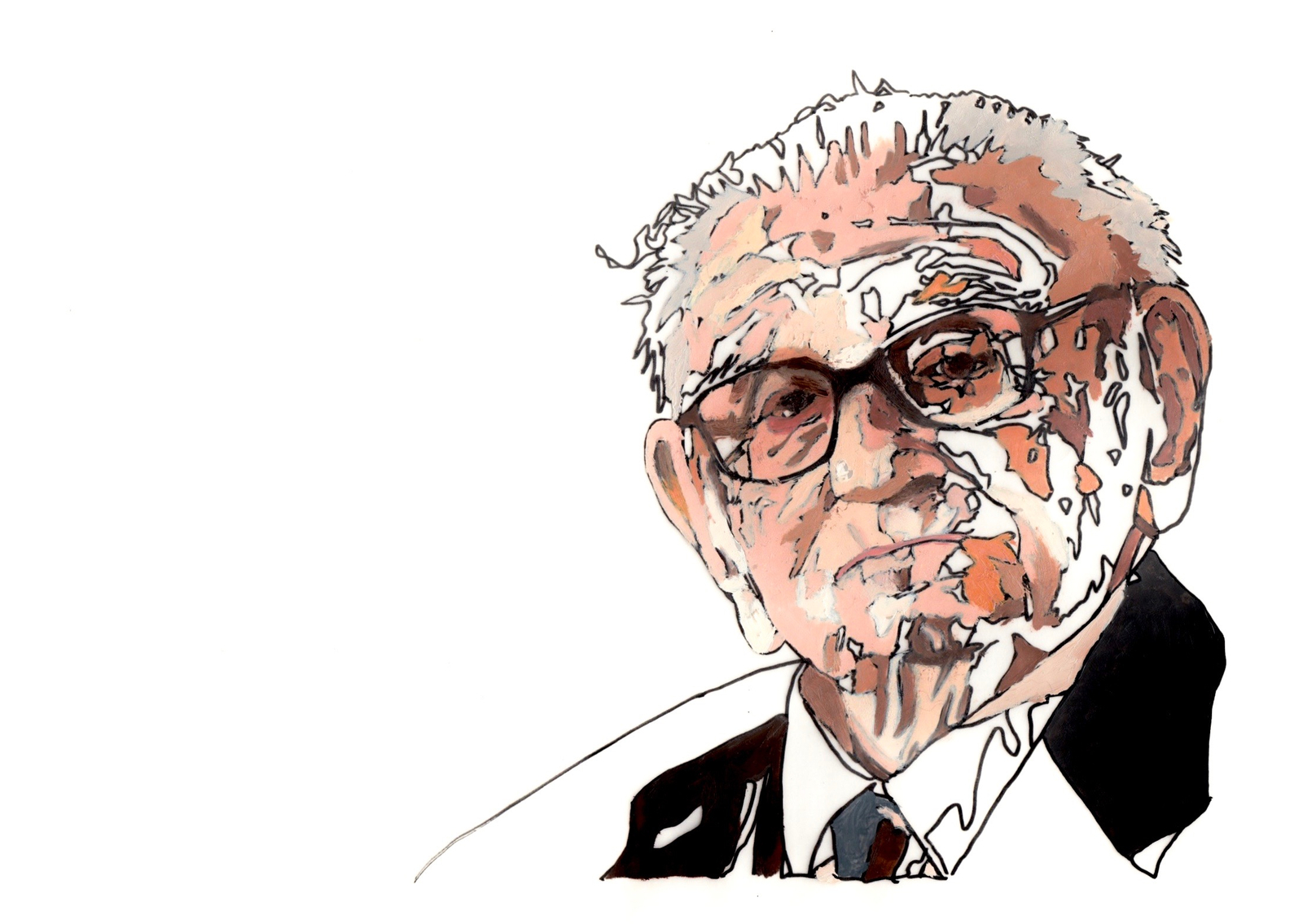

Arguably its biggest protagonist is Nicholas Winton, a British businessman who co-ordinated the rescue of 669 children from Prague. ‘The lay observer may be forgiven for believing that the history of the scheme starts and ends with Winton’, wrote Sharples. In 2003, Winton was both knighted and the recipient of the Pride of Britain Award for Lifetime Achievement; he has subsequently been named a British Hero of the Holocaust by the British Government, and a minor planet, 19384 Winton, was named in his honour by two Czech astronomers.

Winton, who has always downplayed his role and never sought recognition, has often been called the ‘British Schindler’.

While such a tale is satisfying in its ability to apply a narrative balm to the unfathomable horrors of the Holocaust, historian Tony Kushner argues it leads to ‘on the one hand, to the beginnings of heritage construction and, on the other, to the absence of history and critical reflection.’ Kushner’s aim here is not to undermine Winton’s exceptional humanitarian contributions. Rather, he is encouraging the reader to think critically about what is silenced as dominant narratives become louder.

Last year, whilst researching the Kindertransport for my final year dissertation on the UK’s treatment of child refugees, I came across an article on the transports’ ‘invisible children’, written by archivist Claudia Curio in a 2004 edition of Shofar, a Nebraska-based journal of specialist Jewish history, tucked away in the back shelves of the Wiener Collection in Russell Square. Curio undertook extensive archival research of the Jewish emigration agencies in Vienna and records of the Viennese Jewish Community, with the aim of unpicking why some children were chosen and others not. She wrote about Sarah Hochheim, a Jewish girl initially accepted and then refused passage on the transports due to her face bearing visible scars from an operation. She did not survive the Holocaust. In trying to find out more about Sarah, I came across more stories of children whose fate rested on the grounds of their attractiveness, age, gender and/or medical records. One of these was Hans Reich, a young boy originally registered on the first transport, whose mother was already in England and able to guarantee him; Hans was removed from the transport at the last minute due to indication on the mandatory health certificate that he was ‘not a completely normal child’. It is not known what became of Hans.

In 1938, the British Jewish Refugee Committee had been operating successfully for five years, accepting Jewish refugees on the condition that they were privately sponsored or their expenses fully met by the Anglo-Jewish community. When the world awoke on 10th November to the news of Kristallnacht — a pogrom which saw the desecration of over 1200 synagogues, over 90 murders and the deportation of 25,000 Jewish men to concentration camps — the committee was asked to formulate a plan whereby ‘the largest possible numbers’ of children could be moved out of the Reich ‘with the greatest possible haste’. The initial number of children proposed for immediate transfer to Britain was 50,000. This being financially and logistically unfeasible, a procedure for selection and prioritisation became necessary. ‘From this emerged the special character of childhood exile’, wrote Curio. ‘Children could not prove their suitability as immigrants through funds or job qualifications – they had to meet other criteria’.

Selection processes for Kindertransportees can be categorised into two waves. The first wave, from Dec 1938 to about March 1939, saw urgency take precedence over suitability, with orphans and those from explicitly threatened families pushed to the front of the queue — 2000 were evacuated in the first four weeks of the scheme. But money shortages saw the Refugee Children’s Movement, the London-based organisation co-ordinating the transports, no longer able to issue group guarantees. This meant private monetary backing and pre-arranged accommodation became a necessity. Children henceforth needed to meet the individual requirements of potential guarantors or foster parents.

Prospective carers could flick through a card index with photos. If they couldn’t find a child who met their specifications, they could submit a request. A typical request, received by the Vienna office, read: ‘We have an enquiry after a four- to six-year-old girl, non-orthodox, preferably an orphan (without a mother), that the family in question can take care of for a long time. We ask you to send us the required documents with photos right away… so that the woman in question can find a child.’ The majority stipulated girls seven to ten, and if possible fair. Boys of twelve and upwards were hard to place – one welfare worker from Prague recalled that children had to be ‘well-bred’, ‘attractive’ and ‘could fit in with [the host family’s] life.’

One particularly desirable quality of a child was a (permanent) lack of parents. More than once, a guarantee that had been given was withdrawn after it emerged that the children’s parents wanted to come to England; often prospective parents made the possibility of adoption a condition of their offer. There were an excess of enquiries about small children and girls – often whose parents were reluctant to send abroad alone – yet teenage boys, who were often seen as being independent enough by virtue of their age and sex to travel alone, had slim chances of finding a guarantor in England. Curio finds that in fact, many orphans were not accepted – ‘in short, there were very few orphans with all the right references.’ Such references included coming from the social milieu that reflected the wishes of British middle classes, not being born out of wedlock and having impeccable behavioural and physical and mental health records. In one case, the committee requested another, more detailed health report for a pair of siblings for whom a private guarantor had been found and financing already secured, because ‘the boy looks depressive and the girl looks emotionally retarded’. The children were later accepted.

It was no secret that the organisers took great care send the children deemed capable of integrating in order to give a positive impression and support further emigration. This bestowed upon the successful children a profoundly adult burden: not only must they assist relatives left behind — many memoirs detail efforts upon arrival to help parents or siblings emigrate — but they prove themselves worthy of rescue and draw sympathy for all those still in Europe. The liberal press sought to emphasise their assimilation and gratitude. The images below of the Kindertransport arrivals, published in the liberal newspaper The Picture Post, look like they could be fresh out of the pages of a Hampshire boarding school prospectus: the boys, like brothers, play football and darts, looking hopefully and bravely into the middle distance as if anticipating what their futures might hold.

Correctly servicing the memory of the Sarah Hochheims of history is not the only reason to examine how we represent and remember unaccompanied child refugees.

When the unaccompanied children brought over on the Dubs agreement came to the UK in 2016-17, the arrivals were subjected to a torrent of racist abuse, suspicion and trial by popular press from much of the general public. In the same way the granting of asylum to the Kindertransportees hinged on the terms and conditions of host families, the Dubs children’s asylum was granted on the condition that only the right kind of children would arrive – young ones with big eyes, smooth skin, and muddy toys, whose childhood would be all but lost if Britain had not extended its gracious arm to save them from their certain peril. The Dubs arrivals, by virtue of not being walking exhibitions of need, vulnerability and gratitude, were deemed to violate the coded terms set by the popular press for their stay.

An image-saturated tabloid culture, Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment’ policy and the right of the far-right in the UK make for a potent cocktail when real, living asylum seekers and refugees are taken as the target – in November last year, a Huddersfield teenager was charged with assault for attacking a 15-year-old Syrian schoolboy; two months previously a teenager in Scotland had been sentenced to seven years in jail for attempting to murder 25-year-old Syrian refugee Shabaz Ali. The NSPCC last year revealed that there were 5,349 incidents of a child being targeted because of their race or religion in 2016/17, up 14% on the previous year. Historical and national memory, an increasingly entertainment-driven mass media and imbalances of socio-political power all work together to form meta-narratives that disproportionately define those with diminished voice and capacity for self-protection. That process of definition has real-life consequences for the men, women and children seeking asylum in the UK who navigate this hostility every day.

As articulated by journalist Gary Younge at a recent talk for the Bristol Cable, ‘we are in the middle of an immense battle of stories.’