Trigger warning: war, violence, murder, rape, torture

Disclaimer: All statements made in the article are the individuals’ views only and do not represent any group or organisation.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has entered its second month, claiming thousands of lives on both sides. Unlike many other wars in recent history, the world has watched intently rather than looking away as Russia’s aggressions dominate the news cycle. While countries in the West have been lamenting the fading echoes of “never again”, many have yet to commit to phasing out Russian fossil fuels – a failure which will undoubtedly enable further aggressions.

The climate movement in Ukraine refuses to be shut down, and has been mobilising to raise awareness of the root causes of the war. Recently, hundreds of thousands of activists around the world marched with Fridays for Future (FFF) in solidarity with Ukraine, and international efforts urging political leaders to phase out Russian fossil fuels are ongoing.

I spoke to three activists from Ukraine and Russia on their experience of the war, what action we need to see from world leaders, and how people can support activists and refugees from both countries.

“The war wasn’t a surprise for me; it was only a matter of time,” says Ihor, who speaks to me from Kyiv, a Fridays for Future flag adorning his room. “When Putin’s aggression began, there were explosions in the streets. In these situations, it’s important to prepare and not panic. We try to evacuate climate activists from cities under attack, or help in any way we can. I didn’t evacuate because my father has cancer and we couldn’t transport him to a different city. Also, if we evacuate, how are we going to protect the world against Russia’s imperialism? So instead, I’m telling people the story of Ukraine. Putin’s most powerful weapon after its nuclear weapons is propaganda. We have to do our best to stop him.”

Anastasiia, who had fled to Germany from Ukraine a week before I spoke to her, tells me: “It’s been stressful. I remember my grandmother calling me at 6am, then reading the news and thinking, fuck, there is a war. At first I stayed because I was afraid of being separated from my brother – men between 18-60 are not allowed to leave the country and can be mobilised to serve. However, every time I heard an alarm or aeroplane, I was wondering whether they would hit us. When they bombed a city close to my home town, I decided that I had to leave.”

She tells me of the confusion surrounding Russia’s propaganda – soldiers had been seen to empty all food from local stores, only to then hand it out as ‘humanitarian aid’. Although Russia had established humanitarian corridors to allow Ukrainians safe passage to flee different cities, they have since attacked civilians attempting to leave through them.

“Their narrative makes no sense, it changes every day. It’s hard to know what Russia wants,” Anastasiia says. “I volunteered in the refugee settlement centres in my hometown and I heard stories from people who were trying to leave [the Ukrainian city of] Kharkiv while Russian soldiers were shooting at their backs. It was hard to listen to. I talked to a woman in [the Russian republic of] Chechnya, where young boys around the age of 18 were forced to fight in Ukraine. The military threaten to rape and kill their mothers and sisters. They don’t want to fight, but they don’t have a choice and are sent to Ukraine to die.”

The war has sent shockwaves around the world, with many countries condemning Russia’s aggression and expressing solidarity with the Ukrainian people.

“I’m so grateful for the support from people in the EU and across the world,” says Anastasiia, “but I feel so sorry for the refugees from Syria and Afghanistan, who don’t even get half of that and face racism on top of it. I wish people recognised they are also continuing to experience the horrors of war.”

The war has also been heavily opposed in Russia, where about 15,000 anti-war protestors have been arrested at demonstrations. Russia has some of the most draconian protest laws in the world, with activists facing intimidation, torture, and long prison sentences.

Vlada, a FFF coordinator in Russia, tells me: “I have been in opposition to the Putin regime all my adult life, and I strongly condemn this current invasion. I have friends from FFF Ukraine who have been bombed by my country. Although they are safe now, sometimes I still can’t hold back my tears. Russia is now also the most sanctioned country in the world, and the coming economic crisis will destroy all my plans for the future.”

In our conversations, there is consensus on the root cause of the war: “Putin gets his power from fossil fuel money, which funds his wars,” Ihor explains, “not just in Ukraine but also Syria, Venezuela and Libya. And European countries finance his regime. During the Syrian war and the Crimean annexation, European leaders were afraid to stop him because the European market depends on Russian oil and gas.”

Anastasiia tells me of numerous attacks on energy infrastructure, including chemical plants, oil factories and nuclear power plants. She believes the solutions are clear: “If we were not dependent on fossil fuels, it would be much harder to have a war. All this devastation wouldn’t be happening. If we had established decentralised solar and wind power across the country, the impact of bombs wouldn’t cut off power on a large scale. Instead, oil and gas companies are using the war as an opportunity to push for more oil and gas production.”

Many countries have now significantly ramped up their plans to shift to renewable energy. But those commitments don’t mean much if they don’t pull the plug on Putin’s gas at the same time. Western governments are still sending billions of dollars to Russia every day, with gas being exempt from many countries’ sanctions. So far, nine European countries and the US have imposed sanctions on Russia – but since the war broke out, the EU has sent €35 billion to Russia for its energy, which makes up about 40% of total consumption in the EU.

“Fossil fuels are the basis of autocracy in Russia,” Vlada stresses. “You don’t have to listen to the demands of your people if you receive a constant income from fossil fuels. If Putin loses oil and gas money, he will no longer be able to finance war and repressions.”

Meanwhile, the UK has been pushing for new gas fields, with the Jackdaw project expected to be approved soon. The government’s new Energy Security Strategy also includes plans for increased nuclear capacity – a dangerous move, according to Ihor: “The last weeks have shown the dangers of nuclear power. Putin now controls Chernobyl and the biggest power plant in Europe in Enerhodar. We need to make very important decisions now if we want to stand any chance, and move towards renewable energy.”

”Activist groups across Europe are calling on governments to stop funding Russian fossil fuel companies like Gazprom, to cut off the resources funding this war,” Ihor explains. “I’m very happy that we have so much support all over the world.” In Russia, resistance is focusing on the immediate impacts of the war. “Our activists have switched to individual anti-war actions,” Vlada tells me. “The climate crisis has now receded into the background for us – but when this nightmare is over, we will take action again.”

Being an activist in times of war can be dangerous. In our interview, Ihor shares his suspicion of being watched, and warns that campaigners in occupied territories have to exercise caution: “Russian special forces try to kidnap and imprison any activists they deem dangerous for the regime.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

The stakes are even higher in Russia, I’m told by Vlada. “Climate activists have always been subjected to repressions. They are unpredictable and random, and previous involvement in climate activism may make them even more of a target as they go on to protest the war .” Some campaigners have already been forced to leave the country to save their lives, Anastasiia recalls: “Russian activists are in immediate danger and are being watched. Recently, two of them witnessed a crime against another activist. Being a witness is dangerous, so they’ve had to flee Russia.”

“People’s assistance should be directed to residents and refugees from Ukraine”, Vlada says, “but if people have capacity to help the anti-war movement in Russia, then they should amplify cases of torture in police stations, criminal cases against anti-war activists and help people leave Russia, especially persecuted activists.”

Upon asking what action we need to see from political leaders right now, responses are unanimous and unequivocal – we need to stop fossil fuels.

“The war has made it clear that the world is too dependent on fossil fuels,” Anastasiia emphasises, “especially Russian fossil fuels.” The EU has set a target to phase out Russian oil and gas by 2027, a whopping five years into the future. Meanwhile, Lithuania and its Baltic neighbours have completely cut Russian gas imports after the gruesome Bucha killings, with immediate notice.

The UK, on the other hand, is planning to end its reliance on Russian gas by 2023 – but prime minister Boris Johnson has been cosying up with Saudi Arabia instead, only days after a mass execution took place.

“Political leaders are doing the right thing by imposing sanctions,” Vlada comments, “but we also shouldn’t buy fossil fuels from other autocracies, dictatorships and repressive regimes either. Replacing Russian fossil fuels with Saudi Arabia’s is a very dangerous decision because it still violates human rights. By buying fossil fuels from such regimes, political leaders are simply feeding new Putins.

“I understand that leaders primarily think about the price of oil and gas in their countries”, she adds, “but cheap fuel costs human lives. We shouldn’t measure it in Dollars or Euros per barrel, but in real people who have already died and will die in the future from the hands of such regimes.”

By taking urgent action to phase out fossil fuels now and prioritising community-owned energy systems, there is hope that future conflicts over or fuelled by oil and gas will become a thing of the past.

While these are difficult times, playing an active part in resisting the status quo is crucial in fighting for a better future. And it is climate activists across the world who are building it now – through their movements, solidarity and compassion.

“I believe there will be better times for the Ukrainian and Russian people,” Ihor says, smiling. “I believe that after this winter, we will see a real spring. And it will be a Ukrainian spring.”

What can you do?

- Donate to Choose Love’s Ukraine appeal

- Read the book Burnt by Chris Saltmarsh

- Read shado Issue 03: climate justice

- Host refugees – especially long term accommodation is needed. Make an effort to help people settle and take time to explain to them how your country works. You can offer accommodation on icanhelp.host, Ukraine Shelter, or the Homes for Ukraine scheme if you’re based in the UK.

- Support the anti-war movement in Russia using this resource

- Follow FFF Ukraine on Instagram and Facebook, and XR Ukraine on Instagram and Facebook and amplify Ukrainian activists

- Follow this Telegram channel holding brands and corporates accountable for continuing to operate in Russia or failing to support Ukraine.

- Follow NotOnlyPutin on Twitter to learn more about why this is not just Putin’s war.

- Take a photo with a sign reading #PeopleNotProfit, #StandWithUkraine, and demand from world leaders to stop financing Russian fossil fuels.

- Volunteer at train stations to help welcome refugees

- Learn about Ukrainian culture and language

Anastasiia Onufriv is an FFF activist and teaches Ukrainian as a foreign language online. She used to run an eco club for teens in her home town before the war. You can follow Anastasiia’s work on her blog.

Ihor Sumliennyi is Fridays For Future Ukraine’s regional coordinator from Kyiv. He organises international communications for FFF activists who would like to help Ukraine.

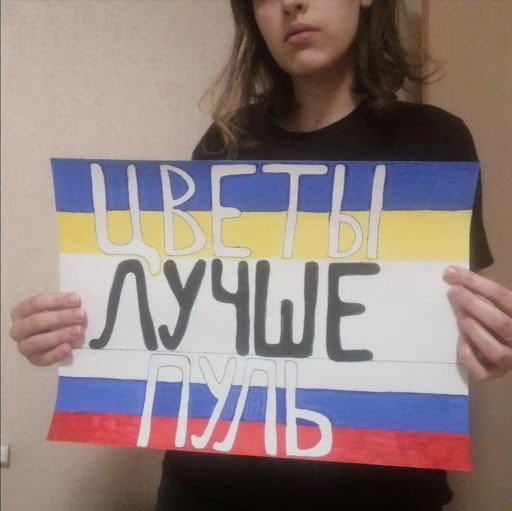

Vladislava Zhuravlyova (“Vlada”) is the coordinator of Fridays for Future Russia. Her sign on the picture translates to “flowers are better than bullets”.