Looking for hands-on, feel-good direct action that supports people and planet? Welcome to the growing movement of wholesome botanarchy.

What is guerrilla gardening?

Guerrilla gardening is the act of planting in public places, in a radically grassroots fashion. In other words: it’s when residents take urban greening into their own hands, with total independence from the council or other civic authorities.

It may help to understand guerrilla gardening as the nature-led arm of “tactical urbanism”: a movement in which residents reclaim public space for public good using unofficial, unauthorised, low cost methods and interventions.

In the case of guerrilla gardening, these interventions involve transforming neglected, lifeless corners of their streets into bright pockets of food, flowers and biodiversity.

So, put simply – whether scattering native wildflower seeds on road verges, or building a community allotment in a vacant lot – guerrilla gardening is where people power meets flower power.

Is guerrilla gardening illegal?

Guerrilla gardening is not actually inherently illegal, because no laws specifically prohibit autonomous planting in public places.

However, law enforcers may use laws and by-laws about property and public spaces against guerrilla gardeners, including accusations of: vandalism, trespass, public nuisance, public endangerment, and environmental laws (e.g. not spreading invasive species).

That said, it’s extremely rare for guerrilla gardeners to be even so much as questioned. What’s more, in cases where they have been charged, the green-thumbed rebels tend to win out over red-faced authorities. Take these two high-profile cases:

Ron Finley, “The Gangsta Gardener”

In 2010, LA city authorities decided Ron Finley’s road verge allotment was breaking a by-law about sidewalks remaining unobstructed. They instructed him to tear up the plants, or pay $400 for a permit to keep them. Ron refused to do either, and started a campaign that was soon supported by major global media. The publicly shamed city council not only backed down, but changed the law: now, Angelenos can plant in their nearest parkway without a permit.

Djo BaNkuna, “The Cabbage Bandit”

In Pretoria, South Africa in 2021, The City of Tshwane similarly issued a fine to Djo BaNkuna for “interfering with municipal infrastructure” by planting brassicas in bare streetside soil. “The Cabbage Bandit” (as he soon became affectionately known) refused to pay the fine and, after representing himself in court, won his case. Amidst this, President Cyril Ramaphosa promised to “ensure the unrestricted development of urban and pavement gardens to increase food security.”

Today, it’s getting even easier to argue our case due to growing public support for green cities and community-led change. A 2022 report in the international journal Crime, Media, Culture described guerrilla gardening as “a form of urban intervention that is broadly accepted and welcomed, even by those who enforce the law.”

That said, it’d be irresponsible of me to claim that there’s no chance of a brush with the forces. Check the latest laws where you live (as best you can), know your rights, and stay vigilant, vigilantes!

When did guerrilla gardening emerge and why?

Around the world, guerrilla gardening emerged in or after times when communities’ common ground was seized by a ruling, colonising minority. (Of course, prior to this – in times when land was a communally managed resource – there was no need for guerrilla gardens, and the concept of itself would be meaningless.)

These earliest guerrilla gardens were created in reaction to people’s sudden loss of their former source of food, medicine, firewood, and other essential resources.

Given the life-or-death nature of these gardens, the earliest guerrillas will have kept these lifelines well hidden, to ensure their survival. So, as David Tracey says, “We will never know the name of the world’s first guerrilla gardener.”

We do know of two early instances of guerrilla gardening, however, that support the emergence-due-to-land-theft hypothesis:

Enslaved African Farmers (1600s – 1700s)

As European forces colonised large parts of the African continent, many enslaved farmers braided native seeds into their hair – as a means to retain agency, food security, and a connection to the homes they were torn from. Landing in the Americas, these experts grew in abundance on their oppressors’ land (itself violently stolen from Indigenous communities).

In contrast to their forced land work, these secret gardens were a form of resistance, survival, and sovereignty. As scholar Geri Augusto says: “They were supplementing their diet, but also it was a small, small patch in which they could be human.”

The Surrey Diggers (1649)

Starting in the 12th century, and picking up pace between 1450 and 1640, the British aristocracy carried out a ruthless campaign of enclosing (i.e. stealing) commons, parcels of land that regular folk (known as “commoners”) relied on for food, fuel, and other essential resources.

In response to the resulting cost of living and malnutrition crises, a group of radicals, now known as The Diggers, began planting vegetables on a hillside. Their aim was to restore the land as “a Common Treasury for All… That every one that is born in the land, may be fed by the Earth”.

They probably weren’t the first group to cultivate a former commons. However, somewhat surprisingly, the Diggers didn’t try to hide what they were doing. Quite the opposite: the group’s leader, Gerrard Winstanley, published reams of campaigning papers. While this succeeded in securing their place in the history books, it also devastatingly led to the immediate destruction of their plot.

Historically, guerrilla gardening has swelled at times of civic unrest and financial crisis – notably in New York City in the 1970s, and London in the 2000s. Today, amidst the rising cost of living, climate and ecological multi-crisis, and growing anti-authoritarian sentiment (against the police, the Tories, our new unelected monarch) guerrilla gardening is once again shooting up through cracks in the streets.

How is the movement evolving?

Guerrilla gardening continues to be a social justice movement, and a retaliation against state neglect, community-excluding urban planning, and capitalist notions of private property.

At the same time, as the climate and ecological multi-crisis worsens, guerrilla gardening is increasingly evolving to target climate justice – fighting back against the urban heat island effect, flash flooding, air pollution, and biodiversity loss.

This climate (r)evolution within guerrilla gardening has also changed what guerrilla gardening involves. Today’s guerrilla gardeners are often guerrilla rewilders: spreading native plant species, and supporting so-called “weeds” – edible, medicinal, pollinator-friendly wildflower wonders such as bugleweed, clover, and dandelions – to survive and thrive.

Why is guerrilla gardening such an impactful form of direct action?

Guerrilla gardens have a range of benefits for both communities and the climate. They boost biodiversity, support mental health, reduce the urban heat island effect, absorb air pollution, provide education in nature, connect communities, grow fresh food, and make a political statement – often all at once!

Although guerrilla gardening isn’t a silver bullet to the crises we find ourselves in, it reminds us that we are not powerless. In creating guerrilla gardens, we are able to plant the seeds of a happier, healthier, fairer future and build a connection to community and nature in the process.

Which communities could most benefit from guerrilla gardening?

Almost 11 million people in the UK live in neighbourhoods with insufficient accessible green space. And the residents of these nature-deprived neighbourhoods are disproportionately low-income people, and People of the Global Majority.

Guerrilla gardening can empower these communities to green their streets. Unlike traditional gardening, guerrilla gardening is accessible to everyone: you don’t need your own garden or allotment to participate, helping to democratise gardening and provide equitable routes into growing and nature connection.

Just as the earliest guerrilla gardens provided food sovereignty for marginalised people, so to this day the likes of Ron Finley advocate guerrilla gardening as a means to combat rising food prices and provide nourishment to those in need (especially those living in urban “food deserts”).

What can you do?

- Watch Ron Finley’s TED Talk.

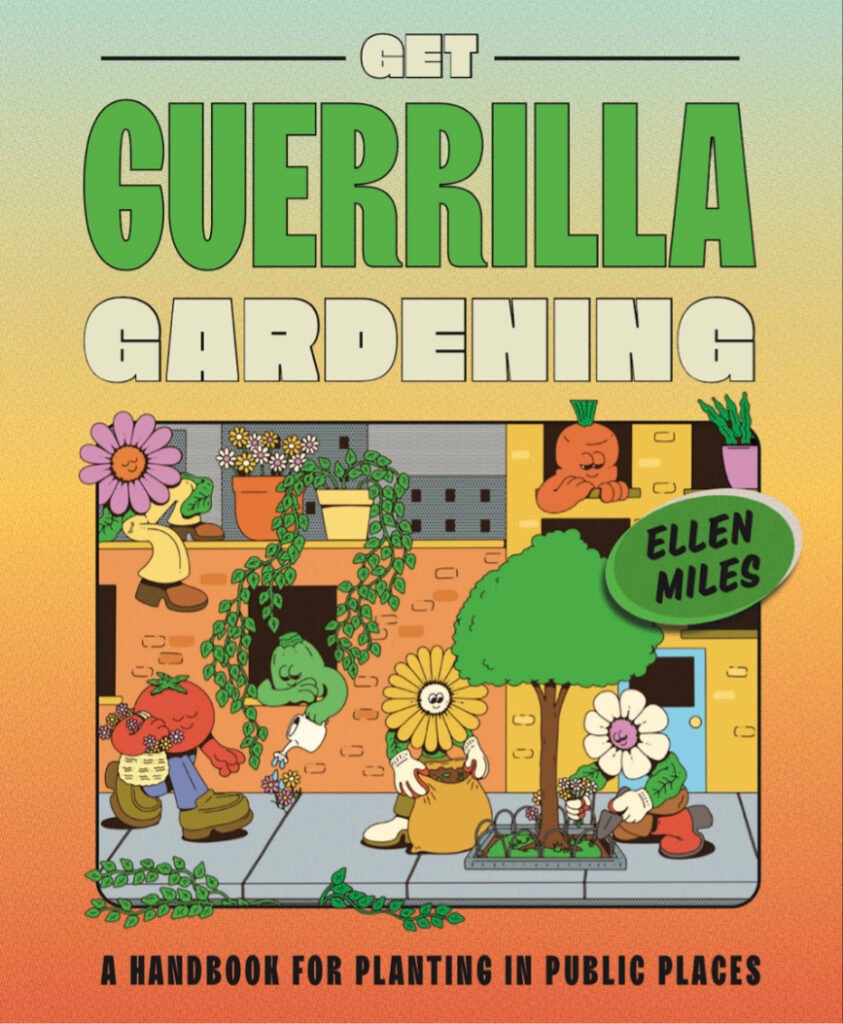

- Read GET GUERRILLA GARDENING, a colourful handbook containing all the information and inspiration you need to create an amazing guerrilla garden.

- Subscribe to updates from dreamgreen.earth, a social enterprise that educates, equips, and empowers people to become guerrilla gardeners.

- Follow these guerrilla gardeners for tips, tricks, and inspiration:

-

-

- TikTok @sfinbloom @sacramentofoodforest @octaviachill (that’s me!)

- Instagram @foodbabysoul @sparkingcommunity @ottawaguerrillagardeningclub

-

- Get guerrilla gardening! Once you feel ready and informed, take action and transform a bleak patch of your street into a little green oasis!

- Read this interview about guerrilla gardening

- Read about trespassing in this article

- GET GUERRILLA GARDENING is the ultimate guide to guerrilla gardening. This hands-on manual contains everything you need to know to start greening your streets. GET YOUR COPY