Juno Roche has written extensively on trans sex and intimacy for years. However, her newly released memoir A Working Class Family Ages Badly offers a deeper and more intentional look at her own experiences.

In recent years I’ve struggled to read books in any length of reasonable time, but this one I breathe in over two sittings – an eye-watering 180 pages devoured in one afternoon on my sofa.

Juno is irresistible, and the prose is relentless and absorbing. It’s not a page turner in the traditional sense, but in reading it, Juno grasps your hand and pulls you along for her journey, and you simply don’t want to let go. You sit beside her as she experiences heroin withdrawal in Egypt, a lover’s intense battle with AIDS, and the terror of the early days of COVID-19 in a remote Spanish village.

In the days leading up to our interview, I’m nervous.

It feels strange to say that I find A Working Class Family Ages Badly affirming, but I do. It’s not often that I, a working class trans person with a typical plethora of trauma, gets to read about someone like them persisting like Juno does in this book – and that alone makes the book very special.

Many of the experiences Juno describes throughout her memoir are harrowing, and I struggle to think of questions about the content that don’t feel intensely personal. I decide that, instead of asking her about her experiences with drugs and sex work, which she speaks of very candidly in the memoir, I’m more interested in finding out about her craft, and reflections on COVID-19, and in particular to gain her insights on the state of trans life, and trans youth. I’ve worked with trans youth for several years now, and I’m still finding my way – so I also hope that I learn something from her wealth of experience.

When I meet her, all my notes go out of the window, because she is just as irresistible in person (or, more accurately, on Zoom).

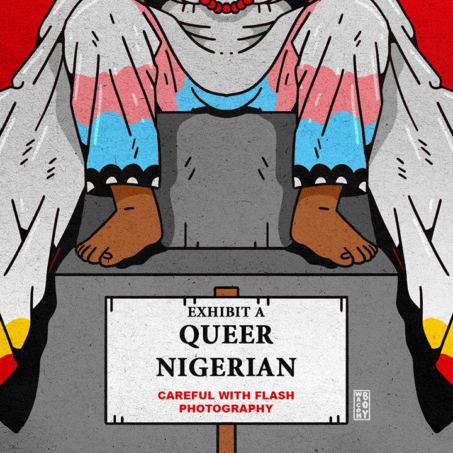

“We’re always given a limited amount of space, and as I’ve gotten older, I’ve just become belligerently joyful about being trans and about being working class and about all the other stuff that I’m about, all those things that intersect in my body,” she tells me – and it shows. Despite the best efforts of transphobic movements both inside and outside the electoral system, trans people like Juno and myself continue to experience untold joy in our communities and in our bodies.

The phrase “queer joy is resistance” is cropping up more and more on tote bags, prints and badges and there’s a reason for that – in a world that wants us to be miserable and scared, being happy feels like a real middle finger to our oppression.

Juno is well used to giving that finger to those who deserve it. She talks openly and passionately about HIV (“it’s just a virus. We get viruses every day – it’s just a virus that they decided to moralise over”), about classism (“I think England has a class system which kills – it kills children’s education”), and about the gender critical movement (“the thing we’re dealing with now that’s really insidious is people not being ignorant – understanding that we can be happy but not allowing it.”)

I discover that Juno wrote A Working Class Family Ages Badly during the early days of COVID-19, and it really captures the intense fear for the future that we all felt in that first year. “For me, Covid had all the intensity of the AIDS pandemic. In a way, it was even more intense, ‘cause everyone was fair game. Everyone was at risk, so everyone was scared.”

You can palpably feel that in the book, and as COVID-19 creeps into Juno’s village you sense that she starts to take better care for herself, physically and mentally.

The intense, traumatic recollections are split up by walks with her dogs up into the mountains, and visits from her mother. It really does feel like you’re sitting on her shoulder, living it all alongside her.

“I didn’t feel safe going in there on my own again, so all of you came with me,” she explains. It makes for an intense and quite singular reading experience, especially if you share some of Juno’s experiences. You feel a real sense of solidarity with her, and after our conversation, I feel solidarity from her, as well.

I came to read A Working Class Family Ages Badly, and to meet Juno, at a bit of a crossroads in my life. I’d made the decision to stop community organising two years after co-founding Trans Aid Cymru, and while I knew it was the right decision for the sake of my wellbeing, something had me feeling guilty.

In her book, Juno recalls with brutal honesty the way that she has carved out space for herself in a world that has kept her at the margins from birth. And in our interview, as I apologise for taking too long to get my words out, Juno fiercely insists: “take as much time as you want! When you are queer and trans and working class, there’s always this rush to be something for somebody, and we really shouldn’t.”

I’m relieved that we’re meeting on Zoom because I feel my throat close up as she says it. It’s something that I hold onto for days afterward when guilt flares, and something I think I will for the rest of my life.

There’s very real external and internal pressures on working class queer people, and on youth in particular. I’m reminded of results day, when thousands of people in comfortable jobs preach on social media that no-one should worry if they have poor exam results. It’s a time where I always ache for young people like me who see good results and a university place far away as their only escape from poverty and abuse. University guarantees money and housing for three years while you figure things out: that is a literal lifeline for working class queer youth. It’s also a hell of a lot of pressure for a 17 year old, when the difference between a B and a D grade feels like life and death.

When there’s no representation for people like you, you have to become a person like them – like the smattering of trans celebrities and influencers who are almost exclusively born from money and given access to private gender-affirming healthcare soon after coming out. You spend your life running towards money, towards things that will be systematically denied you because of your class, or race, or disability, and you’re made to feel like it’s your own personal failing.

Maybe that’s why I feel so strongly about Juno, and about this book. Knowing that someone like me could settle down in a village in Spain and take space for her peace would have been something earth-shattering for me at 17. Honestly, it was fairly earth-shattering for me at 27. My conversation with her really hammered home that it’s not an “us” problem – it’s a “them” problem. “They’re only lesser for it,” Juno says, when I bring up the topic of those who want to deny us access to resources. “We’re getting on with our lives and producing great music and great art.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

She talks several times about wanting to be a mother in the book, and I can’t help but think that she is a mother, at least in a spiritual sense.

We talk about that, about her affection for the next generation of queer youth, and she lights up when she talks about “looking out and seeing this kind of world of brilliance and space and transness and queerness opening up and being completely unapologetic.”

It’s clear Juno adores them. She notes that Gen-Z are the generation that most aligns with her personal politics: “I think I’ve always been like that. The unapologetic-ness is what I’m about. Because we’ve got nothing to apologise for!” Juno has unshakable trust in the trans community, and especially in the younger generations. “All we’ve done is improve the world,” she shrugs. I wholeheartedly agree with her.

I think Juno Roche is the mother that all trans people traumatised by poverty and class look for, and A Working Class Family Ages Badly is a love letter to those like her, from mother to child, to hold their hand. It shows that we, all of us, will experience belligerent joy regardless of the violence of state capitalism and patriarchy raging at us.

What can you do?

- Shon Faye talks about how trans rights discussions don’t adequately include rates of poverty and homelessness in The Transgender Issue

- Sabah Choudrey’s book Supporting Trans People of Colour gives practical advice on better supporting trans people of colour, and the entire trans community as a result.

- Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke’s collection of essays, Transgender Marxism, dives into what it’s like to be trans under capitalism.

- Lindsay Walker’s film “Queens Cwm Rag” follows a group of Welsh drag performers as they climb Mount Snowdon, the highest mountain in Wales, for charity. Watch it here: Queens Cwm Rag

- Shon Faye’s Call Me Mother podcast features short intergenerational conversations between Shon and a range of guests: Call Me Mother

- I wrote for voice.wales about poverty and the trans community in Wales: Our Trans Community Faces A Poverty Crisis, Yet We’re Hounded By The Media

- I wrote for voice.wales about state surveillance and control as a working class disabled trans person: As A Trans Person On Universal Credit, You See How Invasive The State Really Is