Not an economist here, but Canada’s biggest export of 2025 isn’t lumber, or oil, or any of that other boring crap. It’s Heated Rivalry.

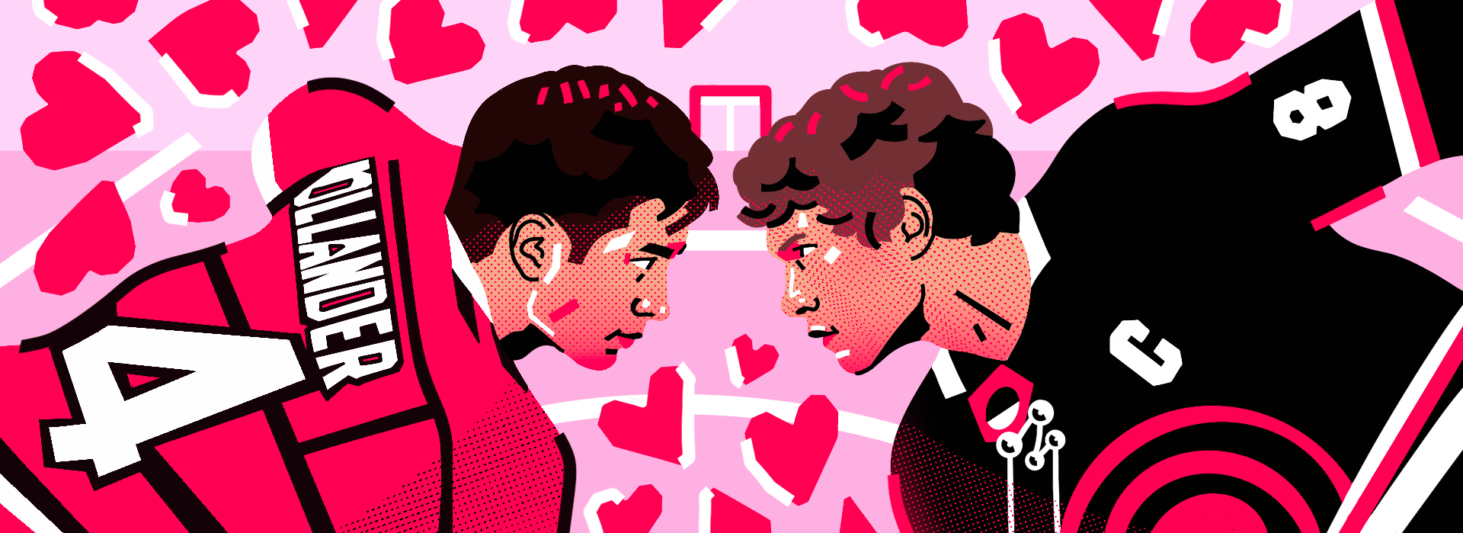

Based on the best-selling Game Changers book series by Rachel Reid, Heated Rivalry follows the years-long clandestine romance between two professional hockey players, all-Canadian boy Shane Hollander and his brooding Russian rival, Ilya Rozanov, as they navigate their attraction for each other in a toxically hyper-masculine hockey setting.

Produced by Crave TV on a relatively small budget, it has become an unexpected breakout TV hit. In the US, it has topped HBO’s list of most-streamed series, and audiences and critics alike have found themselves charmed by the searing chemistry between the series leads. Like show writer-director Jacob Tierney notes: “The slow burn is that they have feelings for each other, not that they are attracted to each other.”

In the lead-up to the Christmas Day series finale in North America, fan obsession and media response has reached fever-pitch. Scroll Instagram or TikTok, and it’s like a gay hockey echo chamber. You’re as likely to find a 20-minute long GRWM with Hudson Williams as you are a heart-wrenching fanedit to 400 lux by Lorde.

The complicated conversation of representation… and why it’s the wrong approach

The other thing you notice about the effusive praise and frenetic fandom is that it comes from a primarily female audience. Women have largely been the producers, purveyors, and consumers of romance fiction – even gay, men-loving-men (MLM) romance fiction – and Heated Rivalry is no different. The romance book market is dominated by a projected 85% female readership, and HBO estimates that about half of Heated Rivalry’s viewership is female.

Like other people in the queer community, I had a natural instinct to raise my eyebrows at Heated Rivalry’s popularity. There aren’t enough gay romance stories out there, and it’s par for the course to be worried about content meant to fetishise, titillate, or objectify. Consequently, queer people also deal with the opposite swing of the pendulum: portrayals of homosexual love that are pointlessly tragic, de-sexed, or just blink-and-you-miss-it representation that ticks a checkbox.

It’s also suspicious to hear straight cis people gushing about queer sexual relationships. Whether it’s creepy men leering at lesbians, or rude and rowdy women in gay bars, the community has had a healthy amount of prickly skepticism around straight people in gay spaces. That was my first instinct when I went to write about the phenomenon of Heated Rivalry – what are generally straight cis women doing in the world of gay hockey players?

The simple answer? This is a different story.

In a world without perfect representation, or enough representation period, subjecting Heated Rivalry to an identity politics discussion around boundaries and ownership neglects the more interesting reality of its existence — and how it sprouted from a rich history of cis straight women, queer women, gender minorities (and yes, gay men) pushing cultural boundaries. They are all part of the environment that made Heated Rivalry possible.

Queering the world of professional sports

Take just the sub-sub genre that Heated Rivalry falls into: gay sports romance. I talked to film and media studies Professor Bridget Kies while I was formulating my thoughts for this article, and she made a connection I had never thought of before:

“It’s not a coincidence that the rise of gay sports romance came with the rise in popularity for women’s sports,” Professor Kies says. “As women’s sports become more visible, so do WLW couples in sports — and then we see a spike in interest for gay sports romances of all kinds.”

This connection is quite evident in the case for Heated Rivalry. Let’s roll the tape: At the final game of the 2019 Women’s World Cup, Kelly O’Hara kissed her girlfriend in the stands after the US victory, de facto coming out of the closet in front of millions of viewers in the stands and at home.

With both the explosion of interest in women’s sports in the past few years and greater acceptance for and representation of out gay female athletes, it may be hard to realise how much O’Hara’s act did to break the culture of silence. But keep in mind, less than 20 years earlier, WNBA player Sue Bird reported that she was pressured to stay in the closet, and play the “straight girl next door” at the start of her career, only coming out in 2017. And now, queerness in women’s sports isn’t a burden or barrier for entry — it’s actually often a draw for female and queer fans who finally see themselves on the pitch.

Flash forward: In 2025, art imitates life: in Episode 5 of Heated Rivalry, based on “The Long Game,” gay hockey player Scott comes out on national television by kissing his boyfriend Kip on the ice. Shane and Ilya watch, transfixed. This was the sign they had been waiting for, that hockey — brutal, misogynist, violent hockey — could be a place for out and proud queer men.

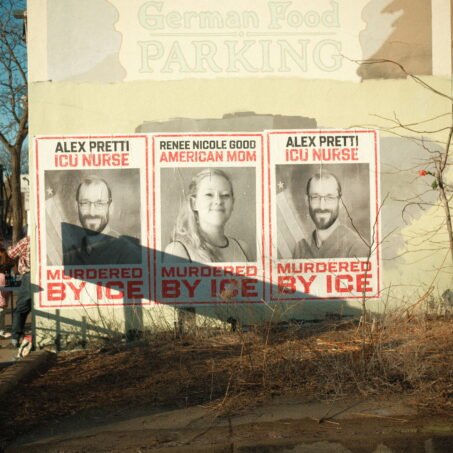

Compared to other sports settings, the National Hockey League (NHL) remains the “last closet,” the final frontier in the big four national leagues — baseball, football, basketball — to not have any players or retired players identify as openly gay. Even as recently as 2023, the NHL came under fire for players eschewing Pride jerseys, the league banning Pride tape on the ice, and the commissioner defending homophobia as “[respecting] individual choice.”

Coach Jackie J, a women’s sports commentator on TikTok, summed it up in a video she made about Heated Rivalry, saying: “I was like, ‘we have so many lesbians in our leagues, and what do the men have?’ And as soon as I had that thought, I was like… what do the men have? The men don’t have anything.”

She continued: “It’s not like there’s no gay players in men’s sports, it’s that there are no out, gay professional athletes in men’s sports.”

A Kelly O’Hara moment has previously been unthinkable for hockey, but Heated Rivalry takes that torch from women’s sports and runs with it, imagining a future where it is possible.

And we’re seeing the toxically masculine hockey culture start to thaw in real time: at the moment of writing, Heated Rivalry is helping to diversify and open the narrative of hockey, from inviting closeted athletes to see themselves in the show, to causing a surge of interest in both the men’s and women’s hockey leagues among gay fans. At a recent game, the NHL played the trailer on the Jumbotron for the crowd at large. It could just be lip service — but it could also be a sign that the last closet’s door may be ajar.

To boldly go where no publisher has gone before

And romance makes the perfect vehicle to shift these expectations and imagine a better future — not simply getting-the-guy, but having everybody live happily ever after. Romance has historically threatened heteronormativity, even before gay romance started becoming popular.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Much like masturbation, reading romance was a long-time deviant behaviour for its majority female audience. Not reproductive in nature? Not male-centred? Imagining a future where your happiness actually matters outside of being a womb? Not worth any social credit. It was to the point where romance publishers were denied space in bookstores for their mass market paperbacks. Instead, they sold books in so-called “women’s stores” – supermarkets, drugstores and retailers.

Despite being a feature of “lowbrow” culture, changes in the romance genre often marked milestones in social progress, especially around sexuality. The first racy bodice rippers were published in the early 70s in conjunction with the movements for sexual liberation and contraception, and it’s also not a coincidence that the sex positivity movement (eg. SlutWalks) and Fifty Shades of Grey were both prominent in early 2010s culture.

Of course, gay romances and their audiences have always existed, but they have usually been relegated to illicit erotica or the cottage industry of fan-fiction, where largely women and gender minorities saw opportunities to interact with well-loved worlds by filling them with characters, storylines, and arcs that they saw themselves in. Fans created the first MLM fan-fiction pairing (Spirk (Spock-Kirk)) in the late 1960s, much earlier than the first mass-market MLM romances. But as queerness was increasingly accepted in society, published gay romances became popular as well, from Heartstopper to Red, White and Royal Blue. Their success has been buoyed by drawing inspiration from and giving kudos to the fanfiction communities that cross over — and help diversify — the romance fanbase.

Today, the normative shifts have caught up. In the last few years, the romance genre has roared out of the furtive shadows, and become a celebrated, highly-profitable sector of the publishing industry. Gone are the days of cheap Julia Quinn paperbacks thumbed over in the secrecy of the home — now, as per my friend in publishing, “we do special-edition smutty romance books, with foil, sprayed edges and a bookmark included,” and people read them in the open.

From Alchemised (Draco Malfoy-Hermione Granger, set in the Harry Potter universe) to The Love Hypothesis (Rey-Kylo Ren, set in the Star Wars universe), bookstores have tables flooded with work from fan-fiction writers. Fan-fiction’s exploration of previously unconventional stories has given us romance bestsellers with monster-fucking, sure, but it also helped mainstream queer stories with happily-ever-afters that you would never have seen on shelves years ago. In fact, some existing fan-fiction pairings might be familiar to Game Changer readers too.

Perhaps today’s widespread popularity of romance defangs its radical history, but it’s good to be reminded that what we take for granted had to be earned: in conversation with Professor Kies, I learned that Carina, the imprint that published Heated Rivalry, made history as one of the first imprints of a major romance publisher to even accept gay romance drafts.

Progress and visibility, for all

The confluence of factors that make Heated Rivalry and its success possible are incompatible with the gatekeeping impulse. It’s not a question of who owns it, or who can consume it, or who should be the creative force around it. Rather, it’s a conversation about how representation and inspiration are contagious, and what’s possible when we have media that privileges the happiness of people who have been written out of the mainstream. It’s a conversation about how powerful it is to imagine better futures, not just the trite getting-the-guy, but everybody living happily ever after.

So now, you have a world where a gay producer, Jacob Tierney, can pick up a bestselling book by female writer, Rachel Reid, and create a global phenomenon centring on a queer love story that is “sweet, sexy, romantic, and, most importantly, happy.” Heated Rivalry is the latest piece of media that shows: everybody benefits from progress and visibility — both in fiction and in real life.

What can you do?

- Heated Rivalry is streaming on January 10th in the UK

- Read more about how romance can inspire us to dream of better futures

- Read more about how reclaiming and queering cultural touchstones can pave the way for change

- Read more pieces by Ning HERE