Strewn across my half-basement bedroom were all the things I had accumulated over the last seven years. Shirts draped haphazardly over my chair. Mismatched pairs of socks. Notes from friends. Pictures of my family, now permanently lodged in the scuffed Dollarama frames I bought during my first week in Canada. Two large, worn suitcases lay gaping, open-mouthed on the floor – the same two suitcases I came into this country with – and the same two suitcases I would be leaving with.

I was not alone. I happen to be just one of 1.2 million temporary residents in Canada who lost their status by the end of 2025, facing a painful choice: leave the country we’ve built our lives in, or remain undocumented.

As we packed up our lives behind closed doors, we watched ourselves be recast as a national problem. In the last two years alone, migrants have become the face of economic anxiety and institutional strain in the Canadian landscape. It really is ironic: to feel so deeply powerless and isolated, while being held solely responsible for a country’s decline.

How did we get here?

My decision to leave Canada came after months of uncertainty, as the clock ticked closer and closer to my work permit expiring, with no means to extend my status. I waited for Express Entry draws that never came. I tried to secure a closed work permit from my employer, and was soon hit by layoffs (thank you, recession).

This cycle has grown all too common. Fellow immigrants have shared similar stories: Permanent Residency cut-offs skyrocketing out of reach, layoffs and cuts looming on the horizon, being forced to switch to closed work permits, leaving them at the mercy of their employers. Despite having studied, lived, and worked in Canada for years, this crop of migrant workers is being quietly pushed out of the country, with no clear pathway to return.

Planning for the future now feels like an exercise in futility. As policy shifts grow increasingly erratic, our lives have been thrown into limbo.

In the weeks leading up to my own departure, my peers had begun booking one-way flights and dismantling the lives they had built here. This led to a number of conversations: about why we came to Canada, what we were promised, and what it feels like to be told, after years of hardship, that we are no longer wanted here.

O, why, Canada?

“I’m doing this to honour my parents in a way,” says Janelle, a fellow immigrant. To her, studying and settling in Canada meant that she could help build a better life for her family back home. At the time, she tells me, it felt like the practical choice: a country that marketed itself as welcoming, affordable, and stable, especially compared to other Western destinations.

That promise worked for me, too. Nearly a decade ago, as I weighed my own options, Canada proudly positioned itself in the global landscape as a multicultural haven – a place that actively courted international students and migrant workers, encouraging them to plant their roots on “Canadian land.” What their honeyed recruiting narratives intentionally omit is that this is, in fact, stolen, unceded, Indigenous land.

“This is literally Canada’s brand, and it erases the extremely ongoing, violent legacy of settler colonialism on these lands by erasing Indigenous peoples,” Harsha Walia, activist and author of Border and Rule, tells me.

“In the current moment, however, it distorts the reality that the vast number of migrants in Canada are not permanent residents or people with pathways to permanent residency,” she continues. In reality, many migrants are on various kinds of precarious visa statuses. Upon arriving here, it becomes clear that Canada is built on a revolving door of labour supply, recruiting workers with the promise of permanence, only to discard them when convenient.

“Canada felt like a safer option to me then, because you didn’t hear about hostility towards migrants like the US,” says Aman, a friend who recently returned to India after his status expired. Canada’s illusion of the ‘friendly neighbour up North’ has lured millions of migrants, just like me. When I first arrived in Canada as a fresh-faced undergraduate student, I knew little about its painful history, or what was in store.

As of 2024, Canada has seen a marked reduction in Permanent Residency admissions, and a tightening of pathways that once appeared stable. In response to the current economic downturn and mounting political pressure, immigration policy in Canada has shifted almost overnight. For the country’s growing population of temporary residents, these changes have rendered long-term planning nearly impossible.

And as we scramble to chase a moving target, it is no secret that these drastic shifts in immigration policy are informed by the rising anti-migrant sentiment in Canada – particularly towards South Asians.

Go back to where you came from!

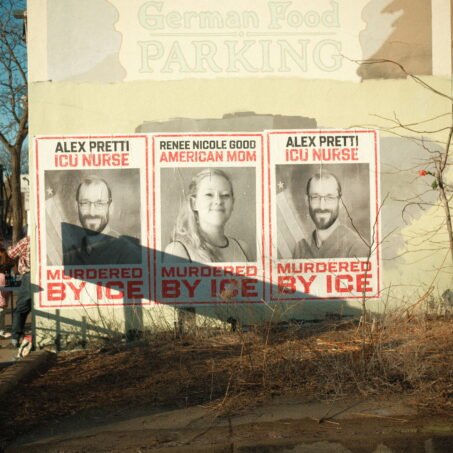

On a particularly bad day this August, I walked head-first into a pole plastered with flyers advertising a “Canada First” rally in my neighbourhood – smack in the middle of Koreatown.

“Stop mass immigration! Start mass deportation! Remigration is necessary!” they read, alongside a cartoonish illustration of Darth Vader holding a shield emblazoned with the Canadian flag.

I was disappointed, but not surprised. As the cost of living continues to climb and public frustration mounts, calls to shut down and ‘secure’ the border are growing louder and louder. Migrants are accused of driving down wages, of undercutting Canadian workers by accepting exploitative conditions.

There seems to be this pervasive idea that migrants are ‘taking over’ Canada amid a global recession, and are a threat to born-and-raised (primarily white) Canadians struggling to put food on the table.

The idea of ‘remigration’ has been positioned, ever so coolly and rationally, as a natural antidote to the financial woes of the average Canadian. But, beneath this framing lies something far more sinister – an ideology rooted in the ‘great replacement’ conspiracy, where the presence of non-white migrants is imagined as a threat to the dominance of a white demographic.

Besides being blatantly racist, violent, and downright deplorable, this ‘theory’ collapses under scrutiny. What this conversation fails to recognise is that migrants are not exactly immune to the recession – they are, perhaps, some of the most vulnerable.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

“Many are working in low-wage work that sustains the Canadian economy, whether that’s literally picking and packing and distributing our food, whether that’s in health care services, whether that’s in service and retail,” says Harsha. “They’re bearing the brunt of the housing and affordability crisis. So, not only is their pain not recognised, on top of that, they’re blamed for it.”

Shutting down the border does nothing to resolve the affordability crisis. What it does do, is jeopardise one of the largest economic subsidies Canada relies on.

In 2022 alone, international students contributed $37 billion to the Canadian economy, supporting over 350,000 jobs. As policies begin to cap the entry of migrants to Canada, institutions are already feeling the pinch, leading to budget cuts and layoffs. International students act as a massive subsidy for the Canadian economy, as do temporary workers, often contributing their taxes to systems that they cannot benefit from, be it financial aid or healthcare.

Instead, hostile policy shifts only serve to push migrants further into precarity.

“When migrants lose their status, they are not deported,” Harsha explains. “They become undocumented – forced to work below minimum wage, in even more precarious conditions. That doesn’t help the labour movement, or the working class.”

The reality is that housing does exist in Canada – it is simply unaffordable. Food prices have spiralled out of control, and the unemployment rate peaked at 7.1% last August and September. Migrants do not engineer this system, nor do they benefit from it: and yet, they are somehow expected to answer for it, absolving those in power of policy failures and corporate greed.

When racism goes mainstream

Racist vitriol circulates freely online, bleeding into policy and everyday interactions. Across the globe, we saw a marked surge in hate speech towards South Asian immigrants as of January 2023.

As a South Asian migrant, watching yourself become public enemy number one wears on you. In the last two years alone, my feed has shifted drastically – filled with racist abuse and misinformation so brazen it would make my skin crawl.

This rhetoric is no longer reserved for fringe forums. Popular creators and accounts like 6ixBuzz TV also hopped on the hate wagon, amplifying inflammatory messaging about immigrants in Canada.

This discourse seeps into our everyday lives: it emboldens policymakers, reshapes how we are treated at work and in our own neighbourhoods, and further alienates us from the Canadian zeitgeist.

What makes things worse, is how this sentiment permeates migrant communities. Even within South Asian communities, newer arrivals are often met with disdain by those who are more settled.

There is a misplaced indignation that this generation did not come to Canada the right way, that international students and temporary workers today are somehow less deserving than those who arrived decades earlier, or than the children of immigrants who now claim distance from new arrivals.

This narrative is an oversimplification, a flattening of history that ignores how pathways to permanence have changed dramatically over time. Older generations often arrived through routes that simply no longer exist: looser labour markets, lower tuition, and clearer pathways to permanent residency.

By turning on one another, South Asians in Canada are forced to compete for dwindling validity, rather than questioning the very system that benefits from our division.

Canada owes you nothing

The retort I often see from Canadians is that those who come to Canada to study or work should do exactly that – and dream of nothing more. Study, then go back. Work, then go back. Do not plan a future here. Canada owes you nothing.

Many of the peers I spoke to were unsure, at first, whether they wanted to settle in Canada at all. But upon arriving here, building community, contributing their labour and creativity, they realised that it slowly became home.

To Canadians, an open border is an act of charity. Immigrants are seen as extractive, as disruptors of the status quo, and Canada may choose to cull them at a moment’s notice. This largely relies on the idea that Canada owes immigrants nothing.

“Canada is not a benevolent nation-state,” Harsha says. “It is an imperial power. Canadian mining interests, arms transfers, and foreign policy – including in places like Palestine – have historically and continue to produce displacement and deprivation elsewhere in the world.”

Migration does not occur in a vacuum. It is a by-product of colonialism, empire, and the extraction of resources. If people suffer the consequences of systems that Canada actively benefits from, then mobility is not a favour to be granted – it is a right owed.

To those who oppose the very idea of immigration, I ask: what would compel someone to gamble everything they have ever known and loved, in exchange for a murky future in a country they have never seen before? For millions of migrants, this decision is not one driven by ambition alone. Economic crises, political instability, and conflict – at the hands of Western powers – push people to seek a better life elsewhere. The privileges that a Canadian inherits by virtue of being born within these borders, are ones that migrants fight relentlessly for their entire lives.

The real question, then, is: who really has the right to a better life?

I asked myself this, again and again, until the day I finally left Canada. I stood in the doorway of my empty room, suitcases in tow. The walls had been stripped of every single artefact, my closet, once overflowing, lay bare.

Whatever I had built here was never mine to keep. After seven years, I left the country with nothing – and that, I realised, was exactly the point.

What can you do?

- Make an active effort to connect with immigrants in your community – make conversation, try to learn more about their stories – the migrant experience is not a monolith!

- Read this piece from journalist Rumneek Johal covering hate crimes towards South Asian immigrants in Canada

- Listen to this CBC podcast segment that delves into the ubiquitous anti-South Asian racism across Canada.

- To gain a deeper understanding of the fallacy of the ‘migration crisis’, read Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism by Harsha Walia.

- Read about the Hostile Environment in the UK