It wasn’t the vehicles you noticed first. It was the listening.

In Minneapolis, people began listening differently. Conversations paused mid-sentence. Heads tilted toward distant sounds. A whistle, shrill and piercing, could send a ripple down an entire block. It was the warning system neighbours built for one another: immigration agents nearby.

As norms disintegrated and what people knew to be true collapsed, even the sound of whistles seemed to detach from reality. We began to hear it everywhere, in everything. The shriek of a tea kettle, the hiss of a radiator, the beeping of a car. Even in the utter silence.

That is when the word began to circulate, quietly at first, then everywhere: occupation.

“It feels like you’re under an occupation that never ends,” said Jamael Lundy, a St. Paul resident and Minnesota Senate candidate, when we spoke at the scene of a high-visibility ICE abduction on 11th February. This was the legacy of “Operation Metro Surge,” the immigration enforcement crackdown that has rocked Minneapolis for the last two months.

According to International Humanitarian Law (IHL), occupation describes territory placed under the authority of a hostile army or state without consent.

For many of the residents of Minneapolis, this felt akin to their lived reality over the last two months. Governance experienced as force without accountability, power that was everywhere and yet nowhere answerable to the people living under it.

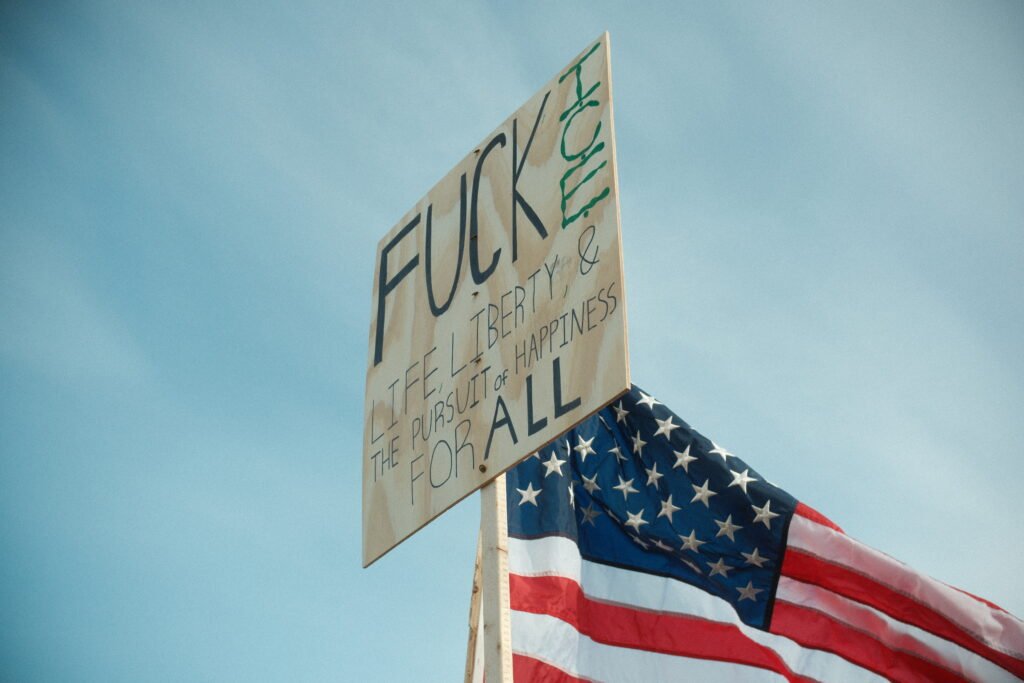

Public conflict between federal enforcement and local leadership deepened the sense that authority had slipped beyond local control. Despite statements by Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey (including the very clear direct: ‘ICE, get the fuck out of our city’) and demands from Tim Walz, they were met with a DOJ investigation for impeding federal operations. This only reinforced what many residents already felt: decisions shaping daily life were being made elsewhere, and imposed here.

And so, for the many Minnesotans I spoke with, they felt like they were living under an increasingly fascist government.

It wasn’t just local leadership being punished for speaking out. Journalists, activists, and protesters alike were being arrested, leading to further fears that our constitutional rights were being violated.

As a journalist myself, I was witnessing the spectacular crumbling of our First Amendment right to Freedom of Press. I’ve seen journalists get pepper sprayed and threatened; I myself have been pushed, aimed at, and hit with munitions – all for doing our jobs.

So when the announcement that Operation Metro Surge is ending arrived on 12th February, people across the Twin Cities – Minneapolis and St. Paul – the reaction was not so much as relief but caution.

We’ll believe it when we see it – became the common refrain.

Why declarations don’t end occupations

An occupation does not end when an authority declares it over. It ends when the conditions that produced it are dismantled: when presence is no longer ambient, when power is accountable, and when daily life no longer reorganises itself around fear.

By that measure, many residents say, nothing essential has changed.

I spoke to several people across the Twin Cities to make sense of the complex emotional landscape that followed the announcement.

A community member tells me: “I want to feel hopeful, like ‘Oh thank goodness, they’re finally leaving.’ But honestly, zero part of me believes that (even if they did), it would return our state to any semblance of normal.”

That distrust is echoed by people observing enforcement in real time. Rory, an ICE watcher and community patroller, tells me that activity has not slowed since the announcement. “ICE is still hitting us hard,” he says. “They’re getting faster, smarter, and changing their tactics. But they’re still here. In the days after the announcement that Operation Metro Surge is over, I haven’t felt like it’s gotten less.”

I heard this echoed across the city. On the surface, you could start to find the traces of normal life seeping back in. Paired with warmer weather, the streets of Minneapolis started to look more vibrant, filled with people – a stark contrast to the empty, ghost-like city of a few weeks ago. But if you looked a little closer, you could still see the fresh scars everywhere.

From a legal vantage point, the picture looks similar. James, a lawyer working with impacted families, says the phone has not stopped ringing.

“Anecdotally, nothing has changed. We’re still getting so many calls a day. Federal agents are hitting people further out in the suburbs now, but I’m still getting calls.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Many fear that this is simply a tactic to divert eyes away from Minneapolis, and that it could simply mean a redistribution of force rather than a withdrawal – one that could become harder to see, harder to track, and harder to contest.

Living inside it

It wasn’t until I briefly left Minneapolis that I could contextualise the intensity of what life had become. I visited family in California for a few days, but couldn’t seem to stop checking my rearview mirror for suspicious vehicles, scanning roads for masked men, and hearing whistles everywhere. What had been protocol and necessary in Minneapolis felt like unfounded paranoia in California, where headlines about ICE existed, but it was possible to move through the day without noticing. You could opt out of awareness.

In Minneapolis, there was no such privilege. The presence of ICE was ambient, impossible to escape.

I would frequently be late to interviews, meetings or events because I would run into some form of ICE operation. Tear gas became a constant presence; I carried a gas mask, goggles, and my camera wherever I went. We learned to clock tinted windows, oversized SUVs, or out-of-state plates as potential ICE vehicles, to check our mirrors just a little longer, just to make sure we weren’t being followed.

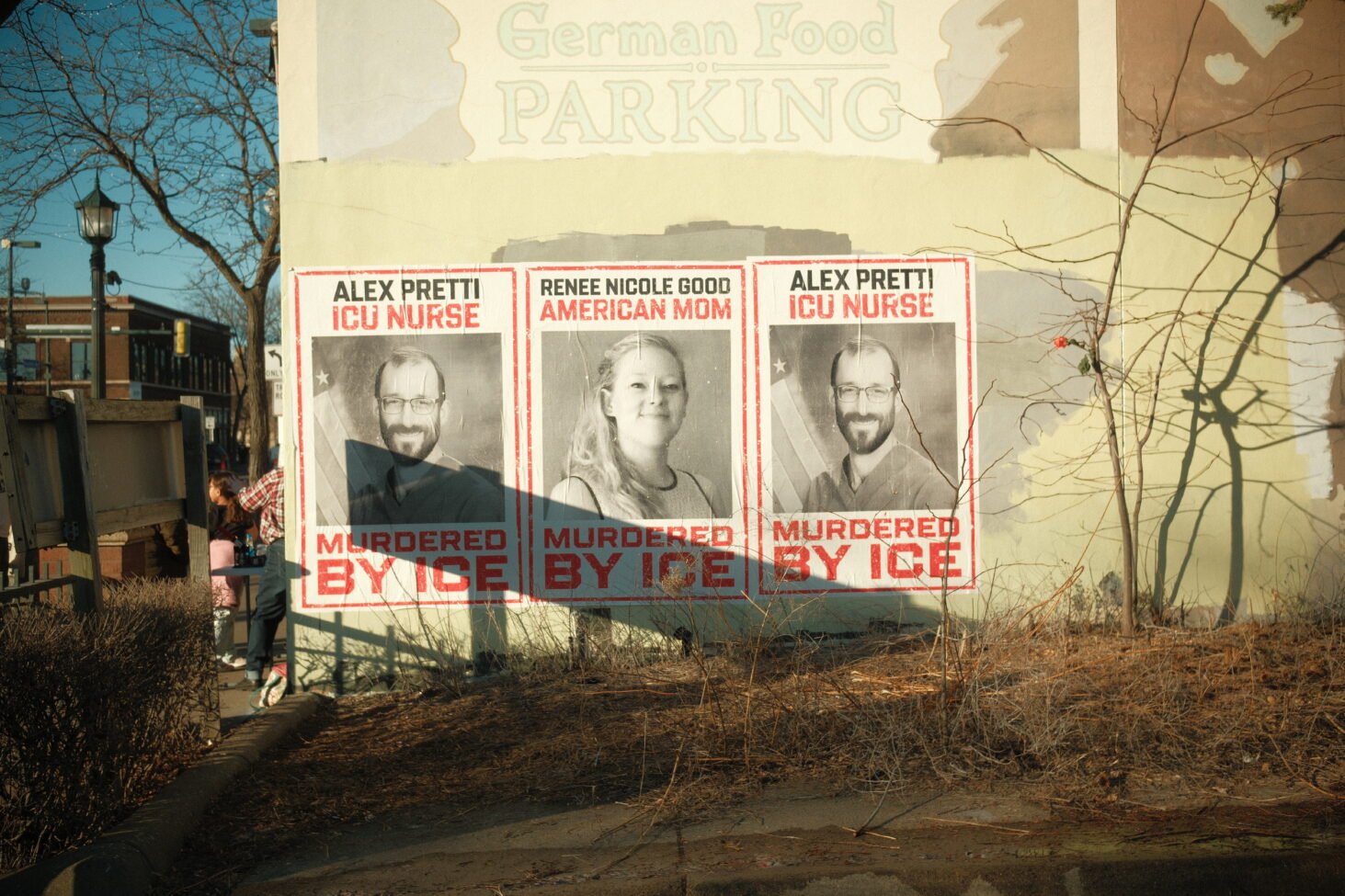

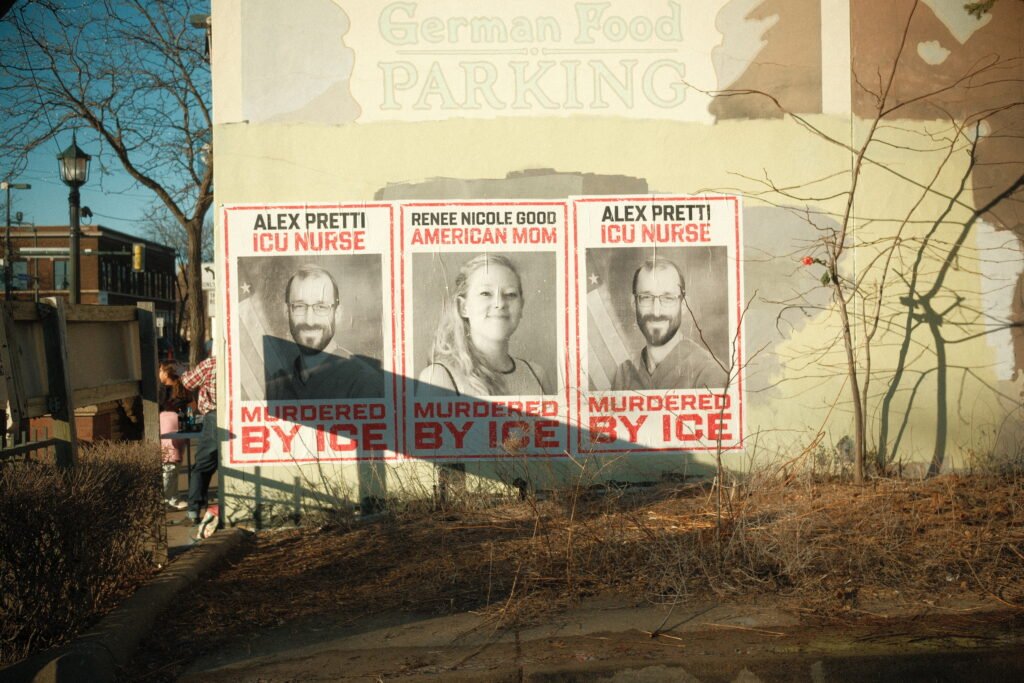

The sentiment unfolded on the walls and street corners too. Graffiti that says “FUCK ICE” adorn the most mundane of urban relics, from unassuming blank walls to stop signs. You can scarcely walk a block without seeing an anti-ICE poster, or the image of Renee Good or Alex Pretti staring back at you. I once counted signage in 80% of the homes on a three-block radius.

Fear and trauma have become a collective experience, one that will take a long time to heal.

I ask a community member on how they viewed moving forward. “There is no ‘unseeing’ our neighbours being ripped from their cars and homes, dragged, chased, beaten, tackled, shot… and sent to concentration camps,” she says.

“I’ve learned that the protocols and behaviour of police, ICE, and anyone who calls themselves ‘in charge’ while carrying a gun creates a tornado of dehumanisation,” she continues. “Simple situations turn into chaos because of secrecy and fear – and it’s amplified by prior trauma.”

Minneapolis has many battle wounds as a city. When asking about what it means to rebuild, nearly everyone here in the Twin Cities mentions the legacy of the George Floyd uprisings. Their trust in law enforcement had already been eroded, but now, it seemed to feel irreparable.

Ed, a longtime community member, describes the rupture in trust as potentially permanent.

“The trauma alone is going to take decades to fix. It might take years to get our neighbours back. And the trust between police, political leadership, and citizens is inconceivably damaged. We’ve watched who stood beside us – and who stood with domestic terrorists.”

Yet despite the harm and havoc brought by the last two months, it had also brought a certain clarity. That while there was little trust to be placed in those in power, there was so much trust to be placed in the community – and that was where the real power lies.

What would it take for this to truly end?

In Minneapolis and St. Paul, people learned quickly that the presence of force is only one part of what makes something feel like an occupation. The deeper shift happens when ordinary life reorganises itself around fear, when neighbours become warning systems, when trust dissolves faster than it can be repaired. That kind of rupture does not disappear with an announcement.

Many residents say the same thing in different words: the damage is not temporary. It is structural, emotional, and relational. Ending a surge of agents is an administrative decision. Rebuilding a civic fabric is something else entirely.

Zola, a community organiser, explains: “I hope this gives us more space to continue to organise and hold our elected accountable and take real actionable steps to remove funding from Minneapolis Police Department, State Troopers, for their complicity in this occupation and their constant allegiance to property over people.”

For many, this was a wake-up call. That the problem stemmed much deeper than the presence of ICE agents – it was the system that enabled and incentivised this institutionalised, large-scale racialised state violence.

As one resident puts it, even if enforcement subsides, “We cannot pretend our society doesn’t need to be rebuilt.” In her view, the ongoing immigration crackdown is only a symptom of a larger historical narrative. “Our entire country has been built by the hands of Black and brown people, enslaved or exploited. None of this is new. It is designed intentionally to commodify people through private prisons, commercialism and whatever the billionaire class feels that day.”

She says the fight is far from over. “This is just the beginning of a revolution, and Minnesotans are showing up. Now we have to figure out how to sustain it.”

And so, despite the declaration that the operation is over, many people don’t believe the occupation has ended. Like they say – and like I, too, now find myself saying: I’ll believe it when I see it.

Instead, across the Twin Cities, one lesson continues to circulate quietly, persistently, as both warning and instruction:

Who protects us?

We protect us.

What can you do?

- Follow MN Ice Watch, an autonomous collective documenting and resisting against ICE, police and all colonial militarised regimes

- Support mutual aid efforts in Minneapolis

- Volunteer for a local community defence/rapid response network

- Read Joi’s other articles on shado