Seeking asylum in the Age of Offshoring

Shrinking space for human rights protection in London, Copenhagen and Berlin

Only a few years ago, offshore immigration policies – the idea of shifting the responsibility of processing asylum claims to a different country – were considered an idea only palatable among the populist far right.

Now, on the brink of unfolding climate emergency and in the midst of a war at Europe’s border, countries are recanting their obligations under international human rights law and pushing for policies that take people who seek asylum out of sight and over the border. In this context, shado mag and Unbias the News present a collaborative investigative series into how these policies are affecting activists and communities that stand for freedom of movement and the right to refuge.

On a Sunday at the end of July, a few hundred people gathered outside the Prinzenbad, a public swimming pool in Berlin. They had come to protest the securitisation of public swimming pools following a racist debate around incidents of young men getting into fights there.

Right-wing politicians and the media had used these incidents to promote racist narratives. By connecting them to increased migration since 2015 and speaking of the consequences of “multicultural swimming” they suggested that migrants, especially young Arab men, were a danger to German society. Their narrative was supported by the fact that the Prinzenbad is located in Kreuzberg, a district marked by Turkish and Arab migration and often referred to by police and the media as a ‘crime hotspot’.

One of the protesters at Prinzenbad held up a sign that read: “Public baths = dangerous? War zones = safe countries of origin? No to borders and security controls.” The sign sums up concisely the issues activists have with the mainstream discourse on migration in Germany over the past years.

On the one hand, certain politicians and media outlets use every opportunity to claim that migrants are a threat to Germany. On the other hand, Germany has played a leading role in the EU’s policy of keeping migrants away from their borders and, ultimately, eroding the right to asylum.

These two developments go hand in hand, with the demonisation of migrants being used to justify the fortification of borders.

They are creating an atmosphere of hostility towards migrants in Germany that expresses itself in the success of right-wing extremist parties like the AfD (Alternative for Germany) and the rise of attacks on those perceived as foreigners.

The discourse around migration puts people’s lives at risk – not just on EU borders but also in European cities like Berlin.

Here in the capital, it can seem as though Germany has embraced its status as a diverse country of immigration. Having moved to Berlin shortly after the 2015 “summer of migration” I have had the pleasure of experiencing the growing of a vibrant Arabic cultural scene, adding to the presence of longstanding Turkish, Arab and other international communities. I love places like Prinzenbad for the fact that veiled women in full-body swimsuits are able to casually hang out there alongside topless sunbathers.

But it feels like every season in Berlin has its own racist debate: this summer, they’ve come for the swimming pools. Last winter it was about some troublemakers with firecrackers who attacked police and fire brigades on New Year’s Eve and sparked a debate about ‘failed integration’ of Arab youths. Instead of looking at the socio-economic issues that lead to violence among young men, these incidents, too, were instrumentalised by politicians to feed on anti-immigration sentiments among their electorate. In this case, the law and order narratives adopted by the right-wing conservative CDU (Christian Democratic Union) party played a major role in helping their candidate win the mayoral elections.

Uniting the EU at the expense of migrants

“Politicians add fire to racist debates, then use them to justify tightening migration laws,” says Tareq Alaows, spokesperson for asylum politics at the refugee-rights organisation ProAsyl.

Tareq, who is 34, came to Germany from Syria in 2015. In 2018, he co-founded several organisations to support people on the move before joining ProAsyl at the end of 2022. The organisation supports people with their asylum cases, documents human rights violations on borders and campaigns for the protection of the right to asylum.

On 8th June, 2023, the EU agreed on the new Common European Asylum System (CEAS). It allows the EU to detain certain people seeking asylum – even families with children – for months in closed camps on the borders until their cases are decided. It also makes it easier to deport them to transit states without allowing them to ever set foot on EU territory, making it more difficult for them to access lawyers and human rights groups.

Politicians, including the German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock of the liberal Green party, claimed that the regulations would not concern migrants from Syria or Afghanistan, as these countries of origin had high acceptance rates in asylum procedures. But this turned out to be untrue, as the CEAS allows member states to treat transit countries as the countries of origin and return migrants there instead of giving them access to a fair procedure on European territory.

While German interior minister Nancy Faeser called the new agreement an “historical success”, critics like ProAsyl believe that it is an attempt by the EU to completely evade its responsibility towards refugees by pushing the issue to its external borders or even to countries across the Mediterranean.

“They said that the new law was necessary to unite all EU countries”, says Tareq. “But they didn’t finish that sentence. They did not say that they united to deprive people of their rights and abolish the right to asylum.”

“Germany is the brain behind new asylum policies”

Much has changed since 2015, when Germany first opened its borders to refugees, and citizens flocked to train stations to support those arriving from Syria and other countries.

The so-called “welcome culture” soon returned to one of hostility: there were calls for an upper limit on people seeking asylum, debates on whether or not to rescue those drowning in the Mediterranean and government campaigns calling on refugees to return to their countries. As the current changes in asylum policies demonstrate, words have been followed by actions.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Most changes in asylum policies have not happened on a domestic level, but an EU one. However, I’m told that “Germany is the engineer, the brain behind the new asylum policies” by Muhammad al-Kashef, a Berlin-based Egyptian human rights lawyer and consultant on migration and border securitisation. “Germany is one of the top countries when it comes to deportations …and the worst migration policies have happened under the German EU presidency.”

I meet Muhammad at Café Kotti in Kreuzberg, not far from Prinzenbad. The smoky café that offers cheap coffee and beer is one of his regular hangouts and a centrepiece of the leftist, queer migrant scene in Berlin – even after the police recently decided to open a station directly next to it to better control what they consider a notoriously criminal neighbourhood.

Muhammad co-founded the El-Foundation, a small non-profit in Berlin that supports people from Africa and the Middle East with immigration-related legal issues. He has already noticed a change in his work: “It has become much harder to apply for asylum. Even when the person deserves the status, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) keeps delaying the process, waiting for the applicant to give up and try something or somewhere else.”

According to Muhammad, the situation is especially hard for low-profile political activists from countries like Egypt that are considered relatively safe and have close relations with Germany. He is currently working with an Egyptian person seeking asylum who was sentenced to death in Egypt and has been struggling for months to prove to the BAMF (Germany’s federal asylum office) that he was being persecuted for political reasons.

If CEAS proceeds through all legal steps, the situation for people like him will get worse. They could be trapped in prison-like camps on the EU borders with no access to lawyers like Muhammad to support them. And the very country they are fleeing from might be paid by the EU to stop people from crossing the Mediterranean.

Tunisia struck such a deal with the EU at the end of June when a European delegation offered the country close to a billion Euros to, among other things, cooperate on “fighting smugglers” and “supporting border management.”

Egypt might be next: “The North African countries have always been against refugee camps on their territory. But with Egypt’s dire economic situation and the massive debt this could become possible,” says Muhammad. What is happening right now is an abolition of the right to asylum, he believes. And: “It is structural racism. The right to asylum was established after World War Two, when Europeans were the ones fleeing. Now that they are no longer affected, they want to get rid of it.”

Making violence against civilians acceptable

It is hard to trace exactly whether the tightening of EU migration laws promotes racist attitudes and attacks in German society – or maybe it is the other way around. But it is clear that both issues have developed in parallel to each other in the past years. The number of attacks on accommodation for people seeking asylum in Germany has more than doubled since last year, after having gradually declined since 2015. They were set on fire, broken into or vandalised with swastikas.

The attacks on refugees, too, have been on the rise since 2022. Reports have shown that three people seeking asylum are attacked per day: spat at, beaten and verbally harassed. The German left party claimed that the developments were related to “the dramatic verbal attacks on the right to asylum, calls for isolation, and ‘The boat is full’ rhetoric.”

In their book Behind Walls, researchers Frank Wolff and Volker M. Heins analyse what effect borders have on those who build them. They claim that borders change society on the inside by creating fear and even paranoia of the outside, which ultimately leads to people’s brutalisation.

Behind Walls reads: “A society’s acceptance of violence against civilians during peacetime is not a given. It needs to be actively established.” The fear of outsiders, Wolff and Heins claim, is not a natural feeling, but “a cultural fact that has to be established to then be instrumentalised politically.” To mobilise more and more resources for border management, unarmed civilians need to be seen as a threat.

“Racism becomes a method of governance,” the authors continue. This, in turn, leads to the stigmatisation of people within the country who are seen as outsiders due to their skin colour, religion or country of origin. “If someone does not want Muslims, Jews, Black people, ‘gypsies’ or ‘Asians’ in their country and fortifies state borders accordingly, they will also want to get rid of the members of this constructed group who are already in the country.”

Anti-Muslim racism across all parties

A vicious circle has emerged, in which politicians have convinced parts of German society that there is a threat beyond the border that needs to be kept out – while the citizens who have internalised this fear demand even stricter migration laws and take out their fearful rage on (perceived) migrants inside the country. When I add “perceived” in this context, it is because many of those that become victims of xenophobic attacks are German citizens born and raised in Germany. Migrant communities have been a part of German society for decades. And yet, to parts of the white majority, Black people and people of colour are still considered “Ausländer” – foreigners. Islamophobia and racism against Arabs have taken centre stage in this xenophobic discourse.

Of course, they are not the only ones who face discrimination in Germany – but it feels like anti-Muslim racism is widely and openly accepted. As the daughter of a German mother who left the church at age 18 and an Egyptian father from a moderately Muslim family, I constantly struggle to fathom the amount of stereotypes and hostility that exist towards Muslims in Germany – even in parts of society that consider themselves liberal or left leaning. But with decades of Turkish and Arab migration to Germany having established a Muslim community that currently makes up more than 6% of the German population, it seems that there should have been more than enough opportunities for non-Muslim Germans to get to know the largest religious minority in their country – and to realise that they are not more prone to terrorism or extremism than any other group in the country.

And yet, in 2014, thousands marched against what they called the “Islamisation of the Occident.” The right-wing extremist political party AfD (Alternative for Germany) has been agitating against everything from women wearing hijabs to pork-free meals in kindergartens, and has alarmingly become one of the most successful parties in the country. And on numerous occasions the CDU party has requested the most common names of perpetrators of violent crimes, trying to prove – although never successfully – that they were not German. But anti-Muslim racism is not just a problem of right-wing parties: even the liberal Social Democratic Party (SPD) supported a law that banned women with headscarves from jobs in public offices like schools and courts.

In the racist debate around allegedly criminal “Arab clans” in Berlin, interior minister Nancy Faeser of the SPD recently suggested that it should be possible to deport family members of criminals, even if they themselves had no criminal record. The proposal of a new legislation came in the run-up to her candidacy for a state election. Even though she and her ministry later distanced themselves from this interpretation of their proposal, such statements leave their marks in the heads of a population already suspicious towards migrants from West Asia and North Africa.

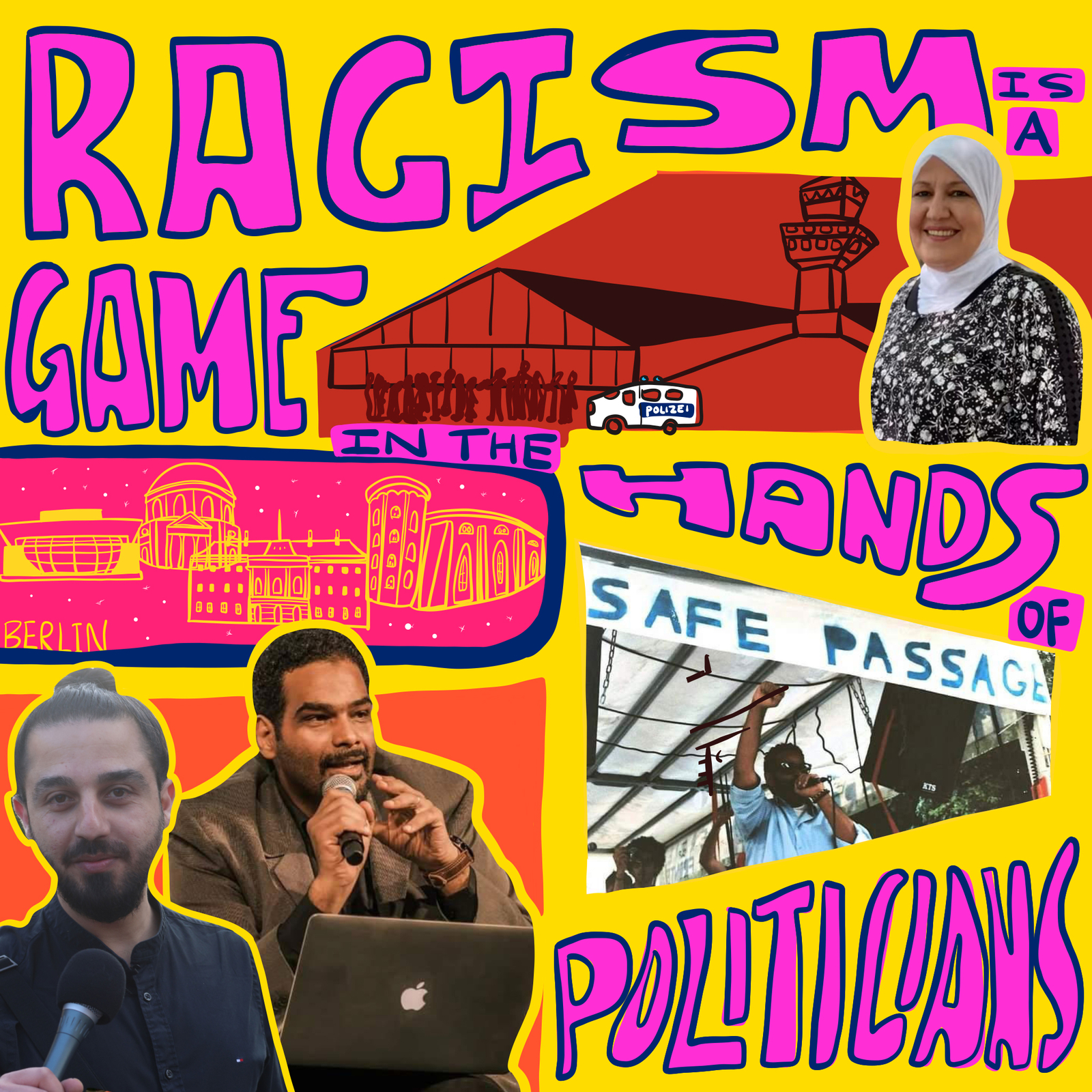

Racism: a game in the hand of politicians

“I was taking a walk in the park with my children. Suddenly, three drunks shouted at us what a ‘disgusting pack’ me and my small children were, while pointing at my hijab. They told me not to procreate and to leave the country.” This story from a Muslim woman in Berlin is just one of many collected by the Alliance against Islamophobia (CLAIM) to document Islamophobia in Germany.

On a hot day in mid-July, researcher Güzin Ceyhan read them out to an audience of women from Syria, Iran and Afghanistan, many of them in hijabs. They were seated in the small, bright space of the ROSA Intercultural Women’s Club, nestled between the high-rise apartment complexes of Marzahn, an economically underprivileged part of Berlin, where the AfD has one of its largest electorates.

ROSA had organised a panel discussion to shed light on “Anti-Muslim racism from a female perspective.” After listening to facts and figures, the women were eager to share their own experiences with racism, whether in public transport, at work or in their children’s schools. Sitting in the back and listening to their stories silently, I thought about what traumatic experiences many of these women had gone through before supposedly finding safety in Germany – and what additional harassment they now had to deal with on a daily basis just because they wear headscarves.

At ROSA, many of the women find support: be it legal, if the attack on them can be prosecuted criminally, or emotional, if they just need to talk to someone who speaks their language and understands their situation.

Someone like Ekhlas Al-Mwaed, a 55-year-old Syrian who has been living in Berlin for five years. At ROSA, she organises programs to empower women from the Middle East and beyond. “I believe the media has a negative impact on the portrayal of Muslims and migrants. Not all migrants are good, but not all of them are bad. We are just normal, like Germans. But whenever a migrant does something bad, there is a lot of focus on it.”

Ekhlas is an affectionate woman who talks fast and laughs a lot. Problems should be addressed, she believes, but it’s the generalisations that bother her. “We do not fear our neighbours,” she says. “We fear the parties. Racism is just a game in the hands of politicians.”

That game is heading in a dangerous direction, Tareq believes: “When the supposed centre parties keep moving to the right, the right-wing parties will feel reassured and become even more extreme in their demands to deprive migrants of their rights. We will see even more attacks on migrants in our society,” he worries.

And yet he remains optimistic when he looks at all the individuals and groups that have been mobilising and supporting each other through these developments. They will not be stopped, he believes: “People have been migrating for thousands of years. There have been attempts to close borders before, but the human pursuit of a safe and dignified life has always prevailed.”

It is not always easy to share Tareq’s optimism: with the AfD growing to second strongest party in some German states (after the CDU, which isn’t a whole lot better)with new laws creating anti-migration facts that will not be undone easily and that will cost many lives on the way; and with racist views sinking ever deeper into people’s minds making it harder and harder to transform them.

The unwillingness of politicians to let go of racist ideologies as a propaganda tool has led to an absurd situation where Germany is sealing off EU borders and deporting migrants, while at the same time trying desperately to attract migrant workers for all the vacant positions on the job market of an ageing society.

But what Tareq says is true: Migration is a fact and it has already transformed the composition of society. The amount of Germans who have a migrant background themselves will just continue to grow and young generations will be way more used to that than those who are most vocal in media and politics right now.

Inevitably, we are moving toward what German researcher Naika Foroutan calls a post-migrant society: a society that stops asking whether or not it wants migration, and instead accepts it as something that has already happened and will continue to happen. It can be dealt with and configured but it cannot be questioned or reversed.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe, www.journalismfund.eu

What can you do?

- Sign Pro Asyl’s petition against detention centers on EU borders and subscribe to their newsletter to be informed about any new protests or campaigns you can join.

- Read CLAIM’s report on anti-Muslim racism to learn more about where this type of racism comes from and what it looks like in everyday life.

- Report anti-Muslim racism that you witnessed or experienced to shed more light on this issue. Report any type of racist attack you experience or witness and find out how to interfere to support victims.

- Join the No Border Alliance in Berlin and Brandenburg to organize resistance against deportation and the fortification of borders.

- Read this collection of articles on the concept of the “post-migrant society” to get inspired about what a society could look like that embraces migration instead of dividing over it.

- Donate to local organisations that support survivors of racist attacks, for example Reach Out e.V. in Berlin.

- Get in touch with the Flüchtlingsrat (refugee council) in your region and find out if you can support them with volunteer work or donations.

- Read about the context in the UK: The floating prison and uncharted waters of UK offshore immigration detention – Shado Magazine

- For more articles about Berlin, read: “We just wanted to give ourselves a chance”: Berlin’s next-gen ravers talk partying and politics