“Our desire is not to achieve respectability, but to demolish the hierarchies that order identities and subjects, recognising us as black, whores, Palestinians, revolutionaries, indigenous, fat, prisoners, junkies, exhibitionists, piqueteras, villeras, lesbians, women and trannies, that although we do not have the ability to give birth to a child, we do have the courage to gestate another History”.

Lohana Berkins

When the LGBTQI+ movement tries to trace the historical genealogy of our trans community, we tend to homogenise the experiences between the countries of the so-called Global North and Global South. With this often comes the erasure of the legacies that imperialism and colonialism imprinted on each region. And if even we, as members of the community, can be complicit in concealing the diverse experiences and histories of our fellow trans brothers and sisters, what is left for the Latin American trans community?

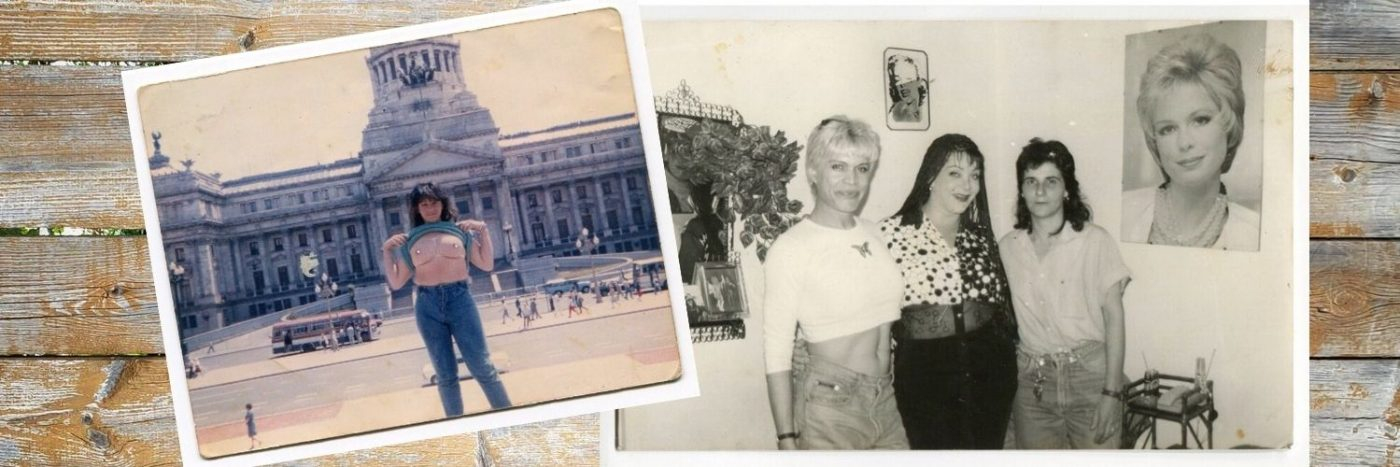

Lohana Berkins was a trans political leader, writer, Indigenous feminist and general coordinator of the Association for the Fight for Trans Identity (ALITT) in Buenos Aires, Argentina (1965-2016). Lohana was one of the leading voices and an undisputed referent of the campaign for the Gender Identity bill throughout Latin America. One of her many contributions to the trans movement was her success in bringing about the recognition of ‘trans’ as a Latin American political identity.

Lohana believed it was impossible to separate the construction of self-identity from the conditions faced by trans folk in Latin society. This experience is often marked by exclusion from the educational system and the formal labour market. Likewise, she suggested that while in Europe and North America the trans experience is commonly ruled by the male-female binary, the Latin American trans experience is claimed as a non-binary identity. In her words: “the objective [of trans identity] is to destabilise the male and female categories.”

In this sense, she was a pioneer in the fight for identity rights. Argentina is one of the most advanced countries of the world in terms of LGBTQI+ rights, having been the ninth worldwide (and second in the American continent) to sanction a Marriage Equality Law in 2010 and having the most progressive Gender Identity Law in matters of sexual diversity – and the first one that does not pathologise trans identities.

Law 26.743, enacted in 2012, allows every inhabitant of the country, whether they are a native or not, to request the registration of sex rectification, and to change their first name and image, when they do not coincide with their self-perceived gender identity. Self-perception is the key word of the law. It implies that medical, psychological, judicial diagnoses of any kind are not necessary (nor are they allowed) to legally change gender in all official documentation, as well as access, or not, to surgeries and hormonal treatments (which are 100% covered by the State) if the applicant wishes for it.

However, although laws exist, they are not always translated into concrete actions. Behind the stories we can find real people, with tangible bodies and material experiences, who day by day endure a transphobic society that seeks to discipline and marginalise them. In this regard, and in an effort to amplify the voices that are not usually heard, I spoke with Candela, a 21-year-old trans woman from La Matanza, Buenos Aires, about what it is like to inhabit a trans body in the suburbs of one of the biggest cities of Latin America. I started by asking her what the right to identity meant to her and her answer stayed with me for the rest of the day. “Identity is something very performative and sometimes even a little irrational. Identity is a right; the simple right to exist as you are, to be able to express yourself, to be able to live, to access any type of opportunity that other people have. It is the right to be”. When we spoke specifically about gender identity and trans identification, she adds: “Trans identities sometimes are repressed simply for expressing themselves, they are being isolated, stigmatised and violated. Identity, for us, is being able to access life in society”.

Her words take on more meaning when we look at the statistics: the life expectancy of the trans population in Latin America does not exceed 40 years. Between hate crimes, exclusion from the labour market, health problems caused by breast prostheses made with airplane oil, and expulsion from the educational system, Latin American trans youth must make their way in the world facing gender, class and ethnic oppression. Residential variables also come into play here, being that in Buenos Aires, the difference between living in the city and living in the suburbs and being LGBTQI + in particular, is big. “Between the suburbs and the capital there is quite a difference, the people in the city have greater access to opportunities. Like in most capitals, there is more movement and because of this more security. For example in the city I could work at nail salons or hairdressers without fearing that people from the neighbourhood would become violent towards me just for being trans. It’s usual to hear stories from many trans people who came from a rural province, or even the suburbs, and have lived horrible experiences that border on dehumanisation. Not because people outside the capital are bad, but because outside of them you’ll find the most deprived and neglected areas, with less presence of the state and access to social resources”, Candela explains to me.

This is usually because despite the legal protections that exist, Argentine society has deep-rooted structural inequalities. When I asked her about the laws that protect her and her community, Candela tells me that although the laws proclaim equality and free access, it does not mean that the public administrators of all the provinces enforce them.“In my experience, I happen to find that hormones cannot be found anywhere due to lack of stock and then a whole series of bureaucratic paperwork is required, delaying their delivery,” she says. The latter generates differences between cities and suburban areas, since in suburban areas it is more difficult to find health centres that have trained professionals equipped to carry out the procedures covered by the Gender Identity Law.

It is possible that the fight of trans resistance organisations and the Campaign for the Right to Identity have managed to disarm this hierarchy , as well as establishing the right to self-perception as a national norm. And, although Candela recognises this issue as regional, the problems faced by the global trans community are also found in the whole of Argentina. “We are used to watching a lot of violence, a lot of segregation, deficiency of information, lack of opportunities, we can see a lot of absence… that is the word: absence. There is practically no day that a trans person isn’t murdered. Obviously, some people want to eradicate us”.

For this reason, it is relevant to highlight a judicial ruling that occurred at the end of March 2021, where a man accused of trying to murder a trans woman was sentenced to 14 years and six months in prison, aggravated by hatred of the identity of gender and its expression. However, the most pertinent thing about the case were the words of the prosecutor during the plea: “for the first time the Argentine Justice recognised a hate crime not only as an attempted murder but also as an attempt to erase what constitutes a person as they are.” This argument is the same one used by the United Nations to classify a genocide as such: a denial of the right of existence to a particular human group. As Candela says as we finish our interview: “I don’t even know if I want people to accept me, I only want to exist without being targeted. We should be able to openly express our identity and our pride to continue here, to continue alive and standing, fighting so that in the future others can have a more accepted life”.

Finally, it is necessary to bear in mind that although the Gender Identity Laws are important historical achievements, resistance does not end in legality. Bureaucratic delays, exclusion from the labour market, expulsion from the healthcare system and constant aggressions are just some of the things that trans folk experience on a daily basis. Furthermore, whilst the laws in Argentina apply to the whole country, they are not equally felt in each corner, with more rural or suburban spaces severely lacking in the relative acceptance which can be found in their cosmopolitan counterparts. Trans lives, and Latinx trans lives in particular, are in danger, exposed to violence and exclusion from a society that turns its back on them. To reverse it, cis people should commit with concrete actions, we must refuse to be complicit in the cis-sexism that surrounds us. It is not enough to not be transphobic, we must be actively anti-transphobic.