This summer, after five years of organising temporary and pop-up exhibitions, the Museum of Homelessness (MoH) opened the doors of its new home in Finsbury Park.

Like MoH itself, its launch exhibition – How To Survive The Apocalypse – turns museum conventions inside out. At its heart is a celebration of people and community – visitors, volunteers, interpreters, contributors and, most of all, its object donors, all of whom have experienced homelessness in London or across the UK.

But Apocalypse doesn’t start with the objects. It doesn’t even start inside the museum. At the outset of our allotted time-slot, visitors gather together in a group, outside the building as weather allows, for a collective welcome that is always warm.

There, the team tells us about this special place, and the urgent context of this special exhibition: the charity Shelter estimates that 309,000 people are homeless in England alone – a figure that includes 1 in 51 Londoners. Government research further shows that almost half (47%) of the families living in temporary accommodation have been there for more than two years.

MoH was set up in this painful context, growing out of a homelessness archiving project into a multifaceted arts centre, campaign, service provider, and educational resource. Its mission is to secure justice and dignity for people widely marginalised and ignored by the public and politicians alike. That purpose is clearly expressed through direct service provision, research and campaigning work. The same drive structures its usual, effective and affecting curatorial approach.

The solutions will always lie in community

The idea behind Apocalypse, as MoH co-founder Jess Turtle has explained, is that “the answers don’t lie in Parliament, they lie here, with us, the people who come up with solutions on the ground and work together to get things done.”

At MoH, the voices and stories of object donors make up the collection – not the objects themselves. It is a subtle distinction that sets the museum apart. Its objects have been collected with intention and care – they are never fetishised and never disconnected from their former beholders’ personal lives.

Their words and wisdom guide our visit. We encounter the belongings and experiences that they have chosen to share with us through oral histories, recorded over months past and performed verbatim by practised members of the exhibition team. We focus intently on one object at a time, listening as a group.

Each narrative touches upon its origins and purposes, and ruminates on layered meanings and value. They are all at once highly personal – delivered with pauses, laughter, breaths and tics – and sharply, sometimes subversively, political. The objects discussed are connected, by their donors, to wider, pressing questions of community, society, belonging and (in)justice.

We are shown a wheeled cart that has carried food, drinks and much-needed supplies through hard streets, in hard times; that’s been patched up and repaired a hundred times. It’s now retired – but ready to go, again, when needed.

We see a staff that’s held up its keeper’s body; been carved, stickered and transformed into a statement of political and personal strength. It speaks of endurance – against discrimination, sneers, and violence.

Gently unwrapped with careful attention, we peer towards a piece of turf that provided grounding, stability and warmth for climate action camp residents – and for its donor, rooted in their mind a new conception of ‘home’. Their words lift up dreams of – and action to build – alternative shelters and communities, to live off-grid as a radical, political choice.

We are taught how to value everyday objects – how to craft waterproof clothing from bin liners. Through acts of creativity, reuse, repurpose, repair, ‘refuse’ becomes ‘refuge sack’. As themes recur, imaginative thinking is revealed as not only necessary for surviving homelessness, but as a source of personality, power and pride.

Transforming tradition, exhibiting care

Each object we encounter has been gifted to MoH, at least temporarily. How long a loan will last is a question to be decided by the donor, not the museum. If they want it back, at any time, for any reason, they just have to ask.

There is no murky or contested question of provenance here; no struggle over ownership or return – and no nameless expert text or authoritative institutional line instructing us on what the objects really mean.

Elsewhere in London, the grand halls and decadent walls of ‘our’ gilded institutions court tourist footfall. Leadership teams at landmarks like The British Museum or the V&A bullishly refuse calls for reparations and repair. They prefer to sell grand narratives of colonial power: a great nation, resplendent with wealth (its plunderous sources acknowledged rarely, at best).

MoH tells a very different, far more truthful, story about Britain. Research, campaigning and direct service provision are central to its wider work. This October, as it does every year, MoH released its annual Dying Homeless report. It found that 1,474 people died while rough sleeping, or living in emergency or temporary accommodation in the UK last year – a 12% rise from 2022.

Launching the findings, Matt Turtle emphasised a national context of neglect – not tragedy: “The systems of care for people living with poverty and homelessness are in tatters after 15 years of cuts and corruption. Labour has not yet set out plans to mitigate the damage caused by the last government and our analysis indicates things are set to get much grimmer unless the government acts now to save lives.”

Objects and storytelling

While MoH reports provide stark figures essential to public awareness campaigns, the Dying Homeless Memorial Page centres on the people behind the numbers: the friends, family members, confidants and creatives who need support and justice – in housing, healthcare, education, work – while our politicians equivocate over taxing the rich.

Apocalypse and the wider programming around it work to similar effect. The exhibition’s unusual delivery and design invites deep reflection. After each narration, we are given space to voice our own questions and thoughts. We are asked what we think and feel; to share as well as to receive knowledge and ideas. Interpretations are nuanced, varied, and debated. Without displacing donors’ narrations as the central authority, together our group engages in a quiet exploration and affirmation of structures of collectivity and care.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

In these moments, the power of objects and stories to move us slowly unfurls. I think back to my own experience of living unconventionally – retreating after a painful breakup to live, and breathe, detached and far from home. I found new community in a disused building that had once been a house, then for a while a cafe or a bar, then reclaimed into rooms ‘rented’ out in unofficial terms, by a keyholder, at a paltry cost. I didn’t ask any questions.

In my room, I stacked vegetable crates into shelves for my clothes. I found a lamp for the woodblock placed beside my bed – a leatherette-covered mattress, raised on pallets off the floor. I took a discarded table frame from the street and topped it with part of a door. I sat there to write, to think, daily. I did not lose the option of return. Once I found my way back to myself, I took it. Few of my housemates could say the same.

At MoH, listening to others’ stories, my mind wanders back to that makeshift desk, in that makeshift room, with its crafted objects that had value and were put to use. Surrounded by structures of care, I reflect more deeply on my own experiences than I have done before. I was not homeless, but I pulled myself away from my life, for a while. It could have taken a different route.

I refocus on the objects before us. Unconstrained by the walls of inert glass cases, they speak to us, prompting reflection and empathy. Facing outwards to the world, they invite visitors in, to listen, learn, understand, relate.

As we move between spaces and objects, we’re all given ribbons by MoH staff or volunteers. By the end, we hold five in total, each with a written statement: ‘Share resources’ / ‘Rewrite futures’ / ‘Question everything’ / ‘Find refuge’ / ‘Build community power and heal together’.

They form a set of instructions, a roadmap, of the only way we might also survive the apocalypse – next time. As we leave, we receive a final gift: a small tin of balm, which both protects and heals. Another political statement, delivered as care.

Changing the narrative

Everyday voices and deeply-valued, everyday things make up MoH because here the ethos and action is focused on care – for people, for community, for ideas. Apocalypse is an experiment and a statement that the careful curation not only of a better museum, but of a better world is already taking place.

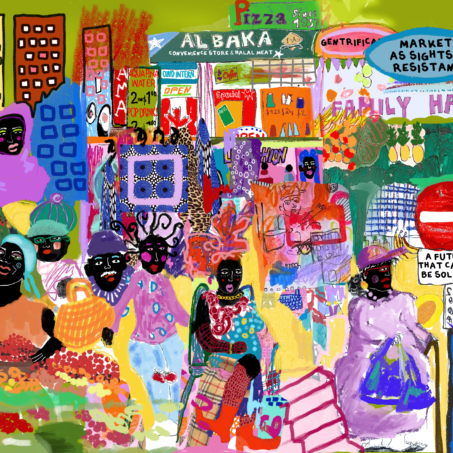

You might not see it, yet. But you will leave MoH knowing that it is being forged on our streets and in shelters, on friends’ sofas and in makeshift homes, led by people written out of official narratives – of the nation, of stories worth telling, of objects with value.

In telling these stories and creating this environment, MoH challenges visitors to reconsider everything they think they know about homelessness – and everything we’ve been taught about what a ‘museum’ can be.

Yet MoH is in many ways just like other museums. It relays history through carefully selected objects, which it keeps safely stored. Visitors can enjoy the gardens; have a cup of tea before they leave. They come along to learn about local people and society. MoH delivers – it just overhauls the national curriculum, along with expectations.

As a centre of learning, it puts its grandiose neighbours to shame. Do not forget: all museums are spaces of political education. They instruct visitors – and people who simply know they exist – of what Britain values / British values. They play a powerful role in society. In its explicitness, MoH however exposes the lies that traditional museums often tell – that they are and must remain ‘neutral’; that their research must not be driven by a political stance.

Apocalypse is set to close soon, as winter nights draw in, allowing the team to focus more fully on responding to community needs. That mission has not paused – at its new home, alongside the exhibition, MoH has been running Family Sundays, educational and practical workshops on topics from sexual health to foot care, the history of squatting to responsible research methods.

These workshops and spaces offer instruction from the grassroots up, on self- and other-care, prioritising people who live on the streets or in hidden homeless contexts. Its weekly community sessions provide art and gardening activities, free supplies and a recovery group.

Its campaigning work isn’t limited to a physical space. MoH’s new podcast series Deep Dive focuses on the human impacts of political policy, each capturing and explicitly debating the MoH mission of securing dignity and rights for homeless people. In doing so, they assure they don’t fall into the charity sector trope of caricaturing or pitying experiences of homelessness – or the politician’s trap of talking about statistics, not people.

In this context, MoH is doing something very different – something radical – in all of its guises: as a museum and arts centre, a direct service provider, a campaign and an educational resource. It is listening deeply, creating platforms for people to tell their own stories and sparking interest and debate in the pursuit of justice, not charity.

Spaces like this often struggle to keep their doors open, and rely on armies of volunteers to open at all. They matter because history matters, politics matter and communities matter. The more radical among them make a stronger argument: people matter – all of us, equally – and our knowledge and wisdom must be valued, shared and treated with care.

While our politicians and institutions keep letting us down, squeezing us dry and pushing us out of secure homes, jobs and health systems, communities are rallying in myriad, creative ways. MoH is an example that teaches us that we can and must challenge the dominant narrative and transform society – one gilded institution at a time.

What can you do?

Do:

- Visit the exhibition, How to Survive the Apocalypse, which runs until 30 November, alongside workshop or special accompanying events

- Explore The Dying Homeless Project

- Support the Communities Not Camps campaign for housing justice for people seeking asylum

- Follow The Outside Project and support its campaign to Make Space for Homeless Queers

Read:

- Big Issue – Vendor Stories

- The London Queer Housing Coalition 2024 Manifesto

- History of Finsbury Park

Listen:

- Deep Dive podcast series